Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History

Review

-

By

James B. Allen,

Gregory A. Prince. Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History.

Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2016.

In 1972 Leonard J. Arrington was appointed Church Historian, the only non–General Authority to hold that position since 1842. Earlier, Elder Howard W. Hunter, adviser to the Historical Department and the previous Church Historian, had told him that the Church needed a professionally trained historian and some new histories. The Church was mature enough, Elder Hunter said, that its history should be more open in its approach than it had been previously. He did not believe in suppressing information or hiding documents that were part of Church history and thought it was in the best interest of the Church to write honest, though discreet, history. Leonard considered this to be his charge. I felt deeply honored when he invited me to become one of his two Assistant Church Historians.

This was a heady time, sometimes dubbed the “Camelot” years because of the exciting new opportunties they presented for Church historians and the numerous books and articles that resulted. The Church Historian’s Office was reorganized so that Leonard became the head of the History Division. He soon gathered around him a group of young, professional historians and proceeded to do what he had been assigned to do. Their work, however, did not sit well with some who were fearful of what a more candid, open approach to history could do to the faith of the Saints, and “Camelot” ended after less than a decade. I experienced all the grand euphoria and deep disappointments of that “golden era” discussed by Gregory Prince in Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History. I was therefore anxious to read this book and am delighted to review it.

Those who pick up this book are in for a most interesting, though sometimes uncomfortable, read. Prince’s book is a stimulating, well-written, hard-hitting biography, based on primary sources (particularly the huge collection of Arrington papers housed at Utah State University), all the available secondary sources, and a myriad of interviews with those who knew Leonard best. I use the term “hard-hitting” because Prince does not shy away from controversy. In fact, he embraces it, going into detail about many controversies, especially those caused by the Church bureaucracy or by a handful of General Authorities who, unlike Elder Hunter, were apprehensive of the new, more open approach to Church history. Prince makes it abundantly clear where he believes mistakes were made and wrongs committed. At the same time, though he admires Arrington, Prince is also willing to point out where he thinks Arrington made mistakes, both in his administrative work and in his writing.

In the first several chapters, Prince deals with Leonard’s early life; his graduate work at the University of North Carolina, where he completed a doctoral dissertation; his courtship and marriage; his time in the military; his move to Utah to teach at Utah State; his initial work in the Church archives, where he conducted research for his dissertation; and his return to North Carolina to complete his PhD.

The rest of the book deals with a wide variety of topics, in somewhat chronological order, that help explain the later life of Leonard Arrington, his pivotal role in the production of Mormon history, and the problems that confronted him. Here is a laundry list of some (not all) of the topics covered: how, with the mentoring of George Ellsworth, Leonard’s PhD dissertation in economics was transformed into an outstanding work of history, Great Basin Kingdom, “that marked a turning point in the telling of Mormon history” (59); the Church’s decision to professionalize and reorganize the Church Historian’s Office and appoint Leonard as Church Historian; the many great qualities that endeared Leonard to those who knew him; Leonard’s deep and genuine spirituality, including the stories of three grand epiphanies he experienced in the years before he became Church Historian; his appointment as Church Historian and the euphoria with which he approached the role; Leonard’s reaction to problems that arose as a result of Church bureaucracy (“rather than working in a conciliatory way with the bureaucrats above his pay grade, he adopted a confrontational posture that worked against him” [199]); the fate of the proposed sixteen-volume history of the Church; Arrington’s mentorship of young scholars and encouragement of other Mormon-oriented historians; his contributions to more fully recognizing the role of women in Church history; the History Division’s role in reversing the Church’s policy that women could not continue their Church employment after becoming mothers; the denial of priesthood to blacks and Leonard’s frustration with that policy; the writing of Brigham Young: American Moses, including the various problems Prince sees in that biography; and Leonard Arrington’s autobiography, Adventures of a Church Historian, which Leonard needlessly feared might bring reprisals. With nearly all of these and other events, there was disheartening controversy and conflict, but perhaps the most disheartening is the story, scattered through a few different chapters, of the efforts of Elder Ezra Taft Benson and a few others to stop the work of Arrington and his associates because of concerns about the kind of transparent, forthright history they were writing. This campaign ended with the eventual dissolution of the History Division at Church headquarters and its transfer to Brigham Young University.

Chapter 20, “Storm Clouds,” focuses first on something that surprised and dismayed all of us in the Historian’s Office: the controversy over The Story of the Latter-day Saints, published by Deseret Book in 1976. This one-volume history, written by Glen M. Leonard and myself, was prepared after Leonard obtained approval from Elder Howard W. Hunter and members of the First Presidency to prepare two one-volume histories: one for publication by Deseret Book and the other to be published by a non-Mormon press. The latter, The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints, was authored by Leonard Arrington and Davis Bitton and published by Alfred A. Knopf in New York in 1979.

In Story we presented the history of the Church as accurately and faithfully as we could, taking into account the most responsible research and, where appropriate, providing the historical context in which major events took place. The book received numerous warm reviews from Mormons and non-Mormons alike. However, it was not long before the book came under fire. In telling the story, Prince is hard on certain “conservative senior apostles”—Elders Ezra Taft Benson, Mark E. Peterson, and Boyd K. Packer—who “did not take kindly to the notion of change—either real change in the Church or change in the way its story was told. Since this was the issue with them, it hardly mattered how devout they [the authors] were, or how carefully they had written their narrative of change” (277).

The book’s most severe criticism is directed toward Elder Benson, and Prince goes into great detail explaining Benson’s core beliefs about God’s hand in the founding of America and the Church and his fear that discussing either of these in a historical context would lead readers to conclude that the key events and key principles of Church history were the result of circumstances rather than revelation. “Indeed,” says Prince, “he did not even need to read the book (and he later acknowledged that he had never read it) in order to have it in his crosshairs, for the real issue was not a book but a philosophy of historiography” (280). Prince refers to Elder Benson’s scathing critique, provided by one of his personal assistants, but says that the book’s so-called inaccuracies were not really the issue. “The real issue,” he says, “was that Benson was determined to terminate the History Division, and Story was simply the catalyst that initiated the process. While it took another six years for him and his allies to complete their work of disassembly, it was already ‘game over’”(284). The idea that Elder Benson was thinking of dismantling the History Division from such an early date is new to me, but, if true, it helps contextualize certain back-channel communications among employees working in the Church History Library and why Elder Benson once expressed to me his concern that the History Division was filled with “a bunch of liberals.”1

Prince goes on to explain the various problems Leonard Arrington faced as concerns about what he considered honest and faith-building history continued to mount. Even though he hurt terribly inside, his public face was always optimistic, and he personally believed that an open, transparent history from faithful scholars would only help the Saints maintain their faith. This point is stressed throughout the book.

Prince discusses in some detail the appointment of Elder G. Homer Durham as managing director of the department, the change in direction that he instituted, his eventual replacement of Leonard as Church Historian, and the dismantling of the History Division when Leonard and most of his remaining staff were transferred to the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute of Church History at BYU. (By that time, I had resigned and returned to BYU full time.) Prince’s concluding paragraph in the chapter on “Disassembly” carries a tone of sadness that accurately reflects how everyone in the division felt at the time: “The era of Leonard Arrington and the History Division, an era that had begun with great promise and that produced unprecedented scholarship and publications, ended with resounding silence, not even punctuated with formal closing. . . . A ten-year experiment in church-sponsored historical research had ended” (351).

A final chapter, “Legacy,” covers Leonard’s decline and death, then briefly discusses his legacy as a publisher, his marvelous collegiality, his indirect mentorship of a younger generation, the respect he gained from non-Mormon scholars, and his commitment to the pursuit of knowledge and telling the truth. This is followed by an epilogue that begins by characterizing Leonard as a “packrat” and then discusses his decision to leave his mountainous collection of papers to Utah State University. Even this action, however, created controversy, since the Church attempted unsuccessfully to claim a major portion of the papers. This vast collection, Prince concludes, is “without question, one of the most important archival sources on twentieth-century Mormonism” (464).

As well researched and well written as this book is, it is not without its problems. In a few places, it seems incomplete, and in others, the information seems wrong. With reference to The Story of the Latter-day Saints, for example, I wish Prince had rounded out the story a bit further. Criticism of the work came from only three of the Twelve Apostles, and most of the General Authorities liked it. He might have emphasized that more fully, though he does note that President Spencer W. Kimball read it all the way through, liked it, and could not understand why others did not. Further, though Prince does report that the furor died down, he does not report that, in a sense, the book and the department were redeemed since Church-owned Deseret Book continued to advertise and sell the book despite the controversy. Elder Boyd K. Packer, who was on Deseret Book’s board and who is the focus of some of Prince’s criticism, also approved the publication of a second printing without any changes, and we were invited to produce a second edition, with no implication that we needed to change anything. I personally never felt that Elder Packer disapproved of the book as much as the other two Apostles, though he often expressed discomfort with what he saw as dangerous intellectual trends in our society, some of which could be reflected in academic approaches to Church history.

On another matter, I was surprised, and a bit bothered, by the implications in a paragraph on page 401 about the writing of Brigham Young: American Moses. Prince cites an outside source who says that doing this biography caused some conflict between Leonard and his staff, who felt they had put so much work into the research that they should have been listed as coauthors. Further, Prince states that Ronald Esplin’s doctoral dissertation, “The Emergence of Brigham Young and the Twelve to Mormon Leadership,” was a “key component of the biography” (401). He also says that Jan Shipps pointed this out in her review published in the Journal of American History. Later, according to Prince’s 2009 interview with Shipps, she told him that Leonard was upset with her review but that it was an honest review and “what I did in that review was to say that a lot of it came straight out of Ron Esplin’s dissertation, which it did” (401).

This account is largely inaccurate and very misleading. Ronald Esplin, who joined Leonard’s staff very early, had spent many years working with Brigham Young’s papers and probably knew them better than anyone. Leonard drew on him and several other staff members as research assistants, and each of them, especially Ron, provided large amounts of material for him to draw on. However, I recently asked Ron about the report that the research assistants were upset that they had not been listed as coauthors. His answer was that this was not true. They all knew that it was Leonard’s book and that only his name would appear as author. “They were not bothered by this,” Ron said, “because they knew he had indeed written it and that he would acknowledge their contributions, which he did.”

The charge that Esplin’s dissertation was a “key component” of the book and that a lot of it “came straight out” of the dissertation implies that Leonard copied sections from what Esplin had written—a charge of plagiarism (though Prince stops short of actually using that word). All one has to do is compare Esplin’s dissertation with the first ninety-seven pages of American Moses (which covers the period dealt with by Esplin) to see that this argument is totally wrong. I spent a good part of a day doing just that. I found a few block quotes from primary sources, such as the Journal of Discourses or Brigham Young’s journal, that were used in both works, but material introducing and surrounding those quotations was not the same at all. Also, the approach, writing style, and in-chapter organization of the two are so completely different that there is no way anyone can reasonably say that Leonard lifted any of it from the dissertation, even though it was among the most important secondary sources drawn on for those chapters. However, all this may be moot because Prince’s report on what Jan Shipps said in her review is also misleading. In the review, she did not say that “a lot of it came straight out of Ron Esplin’s dissertation.” What she said was, “Because Arrington was able to use those sources [the material in the archives], because he could draw on the work of Ron Esplin and others, work likewise based on primary sources, and because some of those materials may never again be available for study, this biography demands unusual consideration.”2 That’s quite different from what she told Prince in 2009.

According to the title, this book is about the writing of Mormon history, but in a way it leaves Leonard short. Prince says little or nothing about most of Leonard’s books, passing them off collectively as of lesser quality, or about many of his articles. True, none of his books achieved the status of Great Basin Kingdom, and some were reviewed with less than stellar enthusiasm, but a book on Leonard Arrington and the writing of Mormon history should give more space to, or at least comment on, more than a small handful of his additional works. A comprehensive Arrington bibliography published by David J. Whittaker in 1999 (and listed in Prince’s bibliography) lists 66 books, monographs, and pamphlets; 247 articles in professional journals or chapters in books; and 68 articles in nonprofessional journals (mostly Church publications), in addition to numerous book reviews. Many of these were ghost written, and others were coauthored with the other author actually having done most of the work; they vary in quality, and some received poor reviews, but it is important to note that without Arrington’s entrepreneurship, they may never have been published at all.

Some of his works made substantial contributions. For example, in Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation among the Mormons (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), Arrington joined with Dean L. May in resurrecting an important manuscript by Feramorz Y. Fox, adding material of their own, and working it into an important and well-reviewed book on Mormon cooperative programs in the nineteenth century, including a nice chapter on the welfare program from 1936 to 1975. One reviewer called the book “stunning,” “a model of microhistory,” and “a rich tapestry of economic and social experiment from the Kirtland days through the nineteenth century extended down to the modern LDS social system.”3 Prince mentions the book twice, not in terms of its substance, but only in connection with the fact that it was criticized by Elder Benson.

Finally, I believe that Prince gives short shrift to the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute at BYU. As he explains, Leonard was director of the institute from 1980 until his retirement, but he was there only one or two days a week, and during that time, production seemed to lag. There was hardly enough, Prince suggests, to justify the heavy expenditure needed to keep it open. He does not report that upon Leonard’s retirement, Ronald Esplin became the director of the Smith Institute and remained in that position until the institute was dissolved in 2005 and Esplin and some of the staff were transferred back to the Church History Department in Salt Lake. What happened under the auspices of the institute during that time is more impressive, and more important, than Prince suggests.

A thirty-six-page bibliography of the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute, 1980–2005,4 which includes work by some people not part of the institute but who received fellowships or in some other way worked under the auspices of the institute, lists 65 books, 113 chapters in books, one monograph, 145 articles in professional journals, 102 articles in reference works, and 87 other articles. Several of these items, such as Arrington’s American Moses, were begun prior to 1980 but were finished while their authors were working at the institute. Also, in 2005 the Women’s History Initiative Team was founded at the institute, which went on to sponsor significant research and publication in women’s history, seminars, and a class in women’s history at BYU. Finally, and of special significance to what is happening today with the Church Historian’s Press, the Joseph Smith Papers Project was begun under the direction of Ronald Esplin several years before he and other institute personnel were transferred back to Salt Lake City. The legacy of the institute is much more significant than Prince implies.

Despite such omissions, readers of BYU Studies Quarterly who love LDS history will find this book worth reading. It does, after all, tell the story of the latter twentieth century’s preeminent Mormon historian, and tells it well. Major transitions are always difficult, and the importance of this book is that it preserves the story of how hard it really was to navigate the transition from the old to the new approach to writing history. Leonard was the symbol of the new, enthusiastically supported by President Harold B. Lee, Elder Howard W. Hunter, President Spencer W. Kimball, and many other General Authorities. Though they were good, well-meaning people, Elder Benson and those who continually fed him negative reports of what Leonard and his staff were doing were the old guard. The new and open approach to history threatened their long-held conservative values because it implied changing fundamental principles, which was uncomfortable. Leonard and his crew were simply caught in the rapids between the old and new intellectual environment, and even though they did not make it through unscathed, they did make it through, and their hundreds of historical contributions helped lay the foundation for a marvelous new age of historical openness, symbolized today by the Joseph Smith Papers Project. For my own part, one of the reasons I have not publicly criticized those who attacked the new histories is that I recognize that they were well-intentioned, even if the approach they were defending was outdated.

About the author(s)

James B. Allen was a teacher and administrator in the seminary and institute programs from 1954 to 1963, then joined the faculty of Brigham Young University. He was Assistant Church Historian, 1972–79, under Leonard J. Arrington; chair of the BYU History Department, 1981–87; and the Lemuel Hardison Redd Jr. Chair in Western American History, 1987–92. He retired in 1992. He has authored, coauthored, or coedited fourteen books or monographs and around ninety articles relating to Western American and LDS history.

Notes

1. At one time, before Story was complete, I was assigned by Leonard to complete a series of oral-history interviews with Elder Benson, as part of a larger objective to gather oral histories of all the General Authorities. I conducted several sessions, and at the end, Elder Benson complimented me on the interviews, saying that at first he was apprehensive because he had heard that the History Division was filled with a “bunch of liberals,” and my treatment of him had been a pleasant surprise.

2. Jan Shipps, Review of Brigham Young: American Moses, by Leonard J. Arrington, in Journal of American History 73 (June 1986): 190–91.

3. See review by J. R. T. Hughes in BYU Studies 27, no. 2 (1976): 246–49.

4. In the author’s possession.

- From the Editor 57:2

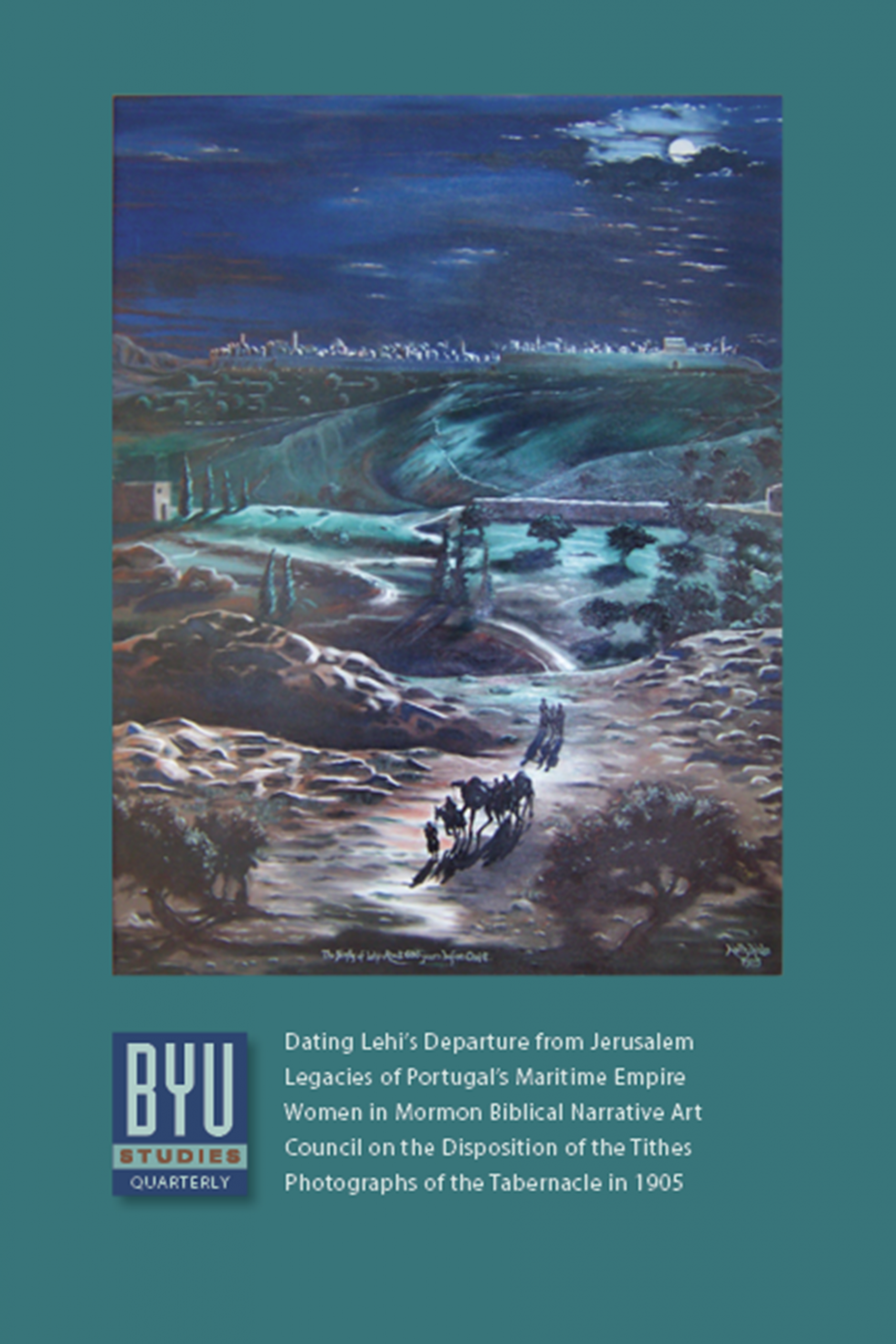

- Dating the Departure of Lehi from Jerusalem

- Wise or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art

- The Development of the Council on the Disposition of the Tithes

Articles

- Mystery and Dance

Poetry

- Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volumes 1 and 2

- Paco

- A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870

- Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History

- The Trek East: Mormonism Meets Japan, 1901–1968

Reviews

- Settling the Valley, Proclaiming the Gospel: The General Epistles of the Mormon First Presidency

- Out of Obscurity: Mormonism since 1945

- Religion and Families: An Introduction

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone