From Manuscript to Printed Page

An Analysis of the History of the Book of Commandments and Revelations

Article

Contents

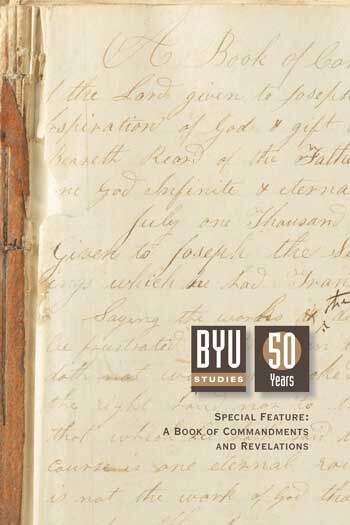

The Book of Commandments and Revelations (BCR) is a surprisingly unpretentious document, judging by its physical condition. Instead of appearing regal and glorious as a symbol of the Mormons’ view of the sacred contents, the Book of Commandments and Revelations looks ragged, worn, and somewhat fragile. The book boards enclosing the pages have been missing for over a century and a half, and replacing this sturdy binding is a cover of material slightly thicker than modern cardstock paper wrapped around the existing gatherings (fig. 1). A number of the volume’s pages were removed and then reinserted, leaving the edges of those sheets brittle, bent, and folded over onto themselves. The handwriting within the volume is small, written in dark ink, and, in more than half the volume, heavily edited by subsequent scribes. In attempting to read the text with its multiple edits and re-edits, the reader might judge the resulting visual experience as a circuitous ensemble rather than a clear display of text as might be found in a printed work.

This brief sketch is not meant to present the text in an unflattering manner. For anyone interested in historical artifacts, the Book of Commandments and Revelations provides a rich experience. From the soft, slightly worn feel of the nineteenth-century paper largely free from impurities that introduce acidic, browning qualities, to the old, musty smell, the manuscript book provides an experience that only a true antiquarian or bibliophilic palaeophile could fully enjoy. Far more importantly, the Book of Commandments and Revelations, while old, used, and remarkably unassuming, provides historians with unprecedented access to the revelations—and the early attitude towards those revelations—that Latter-day Saints held, and still hold, as sacred texts.

Physical Description and Provenance

The Book of Commandments and Revelations was originally a blank book of about 205 ruled pages, marked with preprinted horizontal and vertical lines. The original boards and several leaves from the volume are now missing, with a paper chemise (a brown, heavy, paperboard cover) replacing the original. This paperboard cover was certainly in place by the 1850s, and maybe as early as the 1830s. The probable reason for the volume’s apparent disassembling—publishing the Book of Commandments and the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants—will be discussed later in the article. The volume likely contained nine gatherings of twelve leaves, with the pages measuring about 12.5 × 7.75 inches. A label now adorns the current spine of the volume, reading “Book of Commandments and Revelations,” which is a shortened version of the full title contained on page 1: “A Book of Commandments & Revelations of the Lord Given to Joseph the Seer & Others by the Inspiration of God & Gift & Power of the Holy Ghost Which Beareth Re[c]ord of the Father & Son Which Is One God Infinite & Eternal World without End Amen.” Pages 3–10, 15–22, and 25–26 are missing from the volume, and their location is unknown. Similarly, pages 111–12, 117–20, and 139–40 are missing from the volume, but fortunately the location of these pages is known: they are currently located at the Community of Christ Library-Archives in Independence, Missouri. This apparently random separation and mixed provenance will be discussed later.

Placing the BCR near the top of a short list of important historical LDS documents would not exaggerate its significance. Both scholars interested in Mormon history and lay LDS Church members interested in their religion can study this volume to better understand Mormon history and theology—especially critical due to the influence of the rapidly changing revelations on the early history of the Church. This manuscript volume of revelations, which predates the first canonized publication of Joseph Smith’s revelations by several years, recently became available due in part to the work done by the Joseph Smith Papers Project—a documentary editing endeavor to publish all extant documents created or owned by Church founder Joseph Smith. The Book of Commandments and Revelations, published as part of the first volume in the Revelations and Translations series,1 comprises texts of many extant copies of revelations given to Joseph Smith during the early 1830s previously available only in the early printed canon. It also contains texts heretofore unavailable, including the text to the 1830 Canadian copyright revelation and a sample of the pure language referred to by Orson Pratt in an 1855 sermon.2 The many other revelations contained therein that are not the earliest extant copies hold great value as other textual variants from which to compare and contrast in order to understand, in part, how carefully manuscript copies of revelations were transmitted. Additionally, the BCR proffers a critical piece of evidence to those who study the printing of the Book of Commandments and, to a lesser degree, the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants.

When scholars approach newly discovered documents, several important questions arise. When and why was it created? Who created it? What was it used for? Such analysis is not unlike determining the background of other historical events or individuals. A complete understanding of the content of a document will come only through a proper understanding of the context in which a document comes forth. The excitement surrounding this newly discovered document might entice one into forcing the BCR into an artificial mold—transforming the document into a one-size-fits-all solution to previously unanswered historical questions. However, the first step in a thorough analysis of a document is not to survey the missing pieces in history in hopes that the document will fill those gaps, but to analyze the document itself. Questions basic to archivists in determining the document’s provenance should be fundamental to the historian’s initial approach in order to avoid misinterpretation.3 The contextual understanding of a document’s creation and use leads not only to a better understanding of the content, but also provides an accurate sense of the history surrounding those who created it.4

The questions about a document’s creation arise from an approach that takes into account both document analysis and historical understanding. By carefully studying both internal evidence (the manuscript itself) and external evidence (the archival understanding of historical record keeping and the history of Mormonism in general), one sees more clearly the relevant questions as well as some answers. Both internal and external evidence are required; ignoring the document in favor of historical evidence leads to misinterpretations, while focusing exclusively on the document and not exploring the wider historical context promotes a naive analysis.

A simple example of close document analysis tied to a historical understanding will illustrate this critical point. On several occasions, David Whitmer claimed that the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon, which was in his possession, was the original manuscript.5 A comparison of the manuscript with an understanding of early Mormon record-keeping history leads scholars to conclude that the manuscript previously in Whitmer’s possession was a second copy made for security reasons and sent to the printer. These scholars, however, might conclude that the entire printer’s manuscript was used to set the type for the 1830 Book of Mormon.6 Royal Skousen’s important analysis of the manuscript itself has unveiled the fact that parts of the original manuscript were used to set the type of the Book of Mormon.7 Document analysis contradicting past historical understanding helps us refine our understanding of a document’s later use. Because the BCR is a previously unstudied volume, this paper will examine its basic provenance information, largely leaving the content of the volume for future study.

Provenance: Creation

The Book of Commandments and Revelations was created in a context of early Mormon record keeping, which was initially dominated by the recording of religious texts. Joseph Smith recorded almost twenty commandments before the Church was organized, produced forty-six pages of the Bible revision manuscript four months after the Church was organized,8 and published a religious book of almost six hundred pages—a volume itself based on two different manuscripts of about 450 foolscap pages each.9 In comparison, by the time the Church of Christ made the decision to publish a book of revelations in November 1831, nineteen months after the Church was organized, only about thirty extant pages of “nonreligious” texts had been produced by Smith.10 Clearly, early Mormon record keeping consisted almost exclusively of texts centered on divine communication—the word of God through revelations, inspired interpretation of the Bible, and the miraculous translation of ancient texts “by the gift, and power of God.”11 The BCR epitomized this early record-keeping endeavor—indeed it is the earliest known effort to bring together almost all revelations texts under one cover.

The Book of Commandments and Revelations not only fits within the early Mormon record-keeping context, but it also precedes the beginning of nonrevelation record keeping. In 1832, five different record-keeping projects commenced. True to the emphasis of Mormon record keeping, the first project in 1832 recorded sacred texts, in what is now known as the Kirtland Revelation Book (begun in about February or March). The history of Joseph Smith was begun shortly thereafter in the summer of 1832, but only six pages were created before the project ceased. Joseph Smith’s first letterbook and journal came together that fall as someone gathered the loose letters received in the past three years and collected the thoughts and activities of the founder of Mormonism. Finally, a minute book, later to be known as the Kirtland Council Minute Book, was created about December 1832 in order to copy into one book loose manuscripts of general conference and other meeting minutes.12 The context from which the BCR was created and the subsequent record-keeping milieu it helped create revolved around revelation, inspiration, devotion, and religious activity. A better understanding of this first book of revelations provides a deeper context for divine Mormon texts.

With a preparatory context established, one can now look at other questions surrounding the BCR and address one of the most fascinating and important questions for scholars: When? How early was the BCR created? While no explicit statement exists for the initial dating of this volume, internal and external evidence suggests that it was begun in early 1831. Extant documents from early Mormon history suggest that the first revelations were captured on loose pages and stored together, in some cases sewn together, as was done with the Book of Mormon manuscripts.13 This loose collection undoubtedly proved problematic when a comprehensive compilation was desired for reference, copying, or other uses. Perhaps intending to solve this problem, Joseph Smith and John Whitmer began, according to the 1839 Joseph Smith history, to “arrange and copy” revelations in the summer of 1830.14 This was the first known effort by Joseph Smith to collect all the revelations together and provide an order to them. This summer 1830 project of working with the revelations cannot be definitively tied to any manuscript—including the BCR. Although the history’s report of Smith and Whitmer’s work provides a glimpse of the revelation record-keeping context, the detail provided in the history is sketchy and eight years reminiscent. Dating a manuscript book based on a single reference in the official Joseph Smith history is problematic at best and ultimately unnecessary as the decisive source of dating the manuscript book comes from the book itself.

Archivists use many tools to determine provenance of a document. One such tool is called diplomatics. This centuries-old science originated with the need to demonstrate the reliability and authenticity of medieval documents in courts of law or other official records, but it has recently been adapted, along with many other foundational or semifoundational theories, by archival science.15 Diplomatics involves understanding the process of record keeping by analyzing other manuscripts, learning the contextual history surrounding the scribes, and employing document and paper analysis. Central to the practice of diplomatics is the notion that “the context of a document’s creation is made manifest in its form and that this form can be separated from, and examined independently of, its content.”16 Thus diplomatics, sometimes known as forensic paleography, is the scientific study of texts—using both external and internal evidence—to determine the authenticity of that text.17 In other words, each piece of evidence taken individually proves very little, but taken as a whole, the accumulated evidence points to the likely history of the document.

Tapping into this field of documentary analysis provides an important backdrop for the analysis of the BCR. The analysis includes the document’s form—defined as “the overall appearance, configuration, or shape, independent of its intellectual content”—as well as the document’s structure—defined as “the manner in which elements are organized, interrelated, and displayed.”18 When the form, structure, and makeup of a document are more clearly defined, the content of that document is clarified, and consequently the historical evidences based on that content are more accurate.

The first step in determining the creation date of the manuscript book is to look at the scribal evidences. John Whitmer (fig. 2) was the primary scribe of the Book of Commandments and Revelations, writing in about 87 percent of the existing book, a figure that grows to about 96 percent if it is assumed he wrote on the missing leaves. Since he worked on other scribal projects during the same time period, a comparative analysis between these extant manuscripts and the BCR is possible. Whitmer scribed for Smith possibly as early as the Book of Mormon translation in 1829. From October through December 1830, he occasionally wrote while Smith dictated the Old Testament revision. In about December 1830, Whitmer also copied an Old Testament revision manuscript before going to Ohio. Known before the 1970s as Old Testament Revision 1, this manuscript, now known as Old Testament Revision 3, appears to be Whitmer’s personal copy of the Bible revision Smith had dictated to that point. In Ohio, Smith received a revelation commanding Whitmer to “assist [Smith] in transcribing all things which shall be given [him]” (D&C 47:1). One of these transcription efforts was to again copy the Bible revision, beginning with the Old Testament material in March 1831 and continuing with the New Testament material in late September. Stylistically speaking, the relationship between these copies and the BCR is interesting at least, and at best perhaps provides a clue as to when the BCR was begun. Old Testament Revision 3 was likely begun earlier than Old Testament Revision 2 by about four months. Many elements within Whitmer’s copied revelation volume match Old Testament Revision 2 rather than Old Testament Revision 3 (fig. 3). If the style and copying habits—that is, styles of writing, creation of headings, and the appearance of titles and summaries—of different projects influence one another, then one might assume that the BCR was created sometime after Old Testament Revision 3 and sometime around Old Testament Revision 2.

Another piece of scribal evidence that adds support to an early 1831 date is the dating of the revelations themselves. Whitmer’s volume was made by copying earlier revelations—possibly recorded only on loose papers until then—into one volume.19 Whitmer, who was not present at the reception of many early revelations, did not provide specific dates on the early revelations copied into the volume, and he often supplied only the year of the early revelations. This pattern of dating indicates that Whitmer might not have known the dates of the earlier revelations—meaning they were probably not recorded on the original revelations. As he progressed in his copying work, he began to supply the revelations with more specific dates. One would expect to find that once Whitmer “caught up” in copying the past revelations, he would begin to add days and not just months. He began doing so around what is now D&C 35, received in December 1830. If one looks at all the revelations from the beginning of the volume through November of 1830, there are twenty-six revelations with no specific dates. The next thirteen revelations (through D&C 44, dated February 1831) include four that do not have specific dates. There are thirty revelations from March 1831 to November 1831, and none of them carry generic dates—all have days, months, and years (fig. 4). This transition from generic to specific dating of revelations hints that Whitmer began recording revelations contemporaneous to their reception in late winter 1830 to early spring 1831.20

To expand this scribal evidence a bit further, one notices a common error in the manuscript book, one that could be facetiously called the “check writing in January” phenomenon. Often when writing dates at the beginning of the year, one slips and writes the previous year. Similarly, scribes who copy dated documents sometimes copy the current date, rather than the date found on the document from which they are copying. This misdating of documents is found several times in the BCR. What is now Doctrine and Covenants 30:9–11, found at the top of page 43 of the manuscript revelation book, originally carried the date of “AD 183[blank].” Later, with a pencil, a “0” was added (fig. 5). Several possibilities arise from Whitmer’s omission. First, it was a simple scribal error; maybe Whitmer simply did not finish the year. Another possibility hints at Whitmer deliberately leaving the spot blank, not knowing whether the revelation’s year of reception was 1830 or 1831. Scribes leave things intentionally blank for several reasons, one of which is to return to it at a later time when they know a particular piece of information. If Whitmer exhibited in the manuscript his confusion over the revelation’s reception, one can conclude that Whitmer was copying this revelation in 1831—not 1830. However, an accidental scribal omission must not be ruled out—Whitmer may have just failed to inscribe the final digit.

Two additional instances of Whitmer copying his present year as opposed to the year found on the document occur elsewhere in the volume, with more apparent meaning. When copying current section 28 on page 40, a revelation received sometime in September 1830, John Whitmer misidentified the revelation’s date and wrote “AD 1831” (fig. 6). Another example is found even earlier, on page 32, when Whitmer copied section 24—received July 1830—and wrote “1831,” immediately correcting it to “1830” by writing a “0” over the “1” (fig. 7). No satisfactory explanation, other than that he was copying these revelations sometime in 1831, clarifies this scribal lapse. The likelihood of his writing “1831” while doing his copying in the year 1830 when the date should have indeed been 1830 stretches the imagination to the point of incredulity. The possibility of his writing “1831” while doing his copying in the year 1831, when the date should have been 1830, is a logical explanation and occurs frequently in scribal work.21 Therefore, Whitmer most likely copied sections 24 and 28 in the year 1831, which places his copying work of an early portion of the book during an early part of the Mormon Church’s history, but not contemporary to the dates of reception.

The definition of several archival terms must be used to explain the next evidence for dating the Book of Commandments and Revelations. The initial portions of the BCR have the characteristics of a ledger record rather than a journal record. A ledger book is a compilation of many different original sources usually compiled during one sitting. For instance, in financial records, an original record would be a receipt or bill of sale recorded at the time of purchase. This and many other receipts would be brought together and compiled into a ledger record. The second important characteristic of a ledger volume is the nature of recording: the compilation almost always takes place sometime after the date of the original record. This compilation of a day’s, a month’s, and sometimes more than a year’s worth of records usually occurs during a relatively short period of time. For instance, forty different receipts over a span of ten months may be recorded into a ledger volume on a single day.

On the other hand, a financial journal record—closely related to a daily journal of an individual’s activities—is a daily recording of financial transactions. Over a ten-month period a person might have purchased food from a store twenty times, and the person would have recorded each of those purchases at different times. A journal record is not normally associated with copied original records; however, in analyzing the BCR, the important element of the journal record is a copied register of other more original records, as long as the register is updated on a day-by-day, week-by-week, or month-by-month basis as the documents come in rather than copied over a shorter period of time.

In other words, Whitmer continued to copy revelations into the BCR, but as opposed to when he copied fifteen revelations into the volume in one day (to provide a hypothetical scenario), he copied fifteen revelations into the volume at fifteen different times, depending on when Joseph Smith received a revelation and provided a copy of it to Whitmer. Each type of recording—whether it be ledger copying of twenty items in one sitting or journal copying of twenty items in twenty different sittings—is evident in the form, makeup, and “feel” of the manuscript (fig 8).

An understanding of ledger and journal records helps determine the creation date of the Book of Commandments and Revelations. Unless Whitmer began the copying work by April of 1829 (an impossibility since Whitmer was not acquainted with Joseph Smith at this time), there must have been a period of ledger-type recording when he was copying a number of previously received revelations into the book. This method of recording is apparent in the document. By contrast, once the record becomes a journal-type record—or in other words, when Whitmer began copying revelations as Joseph Smith received them—the volume takes on a different feel. The BCR turns out to be both types of record—both ledger and journal—depending on when various sections were written.

Whitmer did not begin the BCR in July 1828, which is the date of the first revelation recorded by Joseph Smith. Thus, whenever he started it, he had a number of revelations that needed to be copied into the volume over a relatively short period of time This ledger method of record keeping is evidenced by the few breaks and the continuity of the text within certain portions of the manuscript.

When Whitmer caught up with his copying, he no longer copied many revelations at once but instead copied revelations into the volume as Joseph Smith received them and provided them to Whitmer. This time elapse enhances the likelihood for more breaks in the manuscript or a discontinuity of the text, revealing which portion of the manuscript represents a journal record. Breaks can be seen in a shift of the handwriting style, the ink color or flow, and the sharpness or dullness of the quill. The increased frequency of these breaks indicates an elapsed period of time in copying between revelations in a journal-style record.

The transition from a ledger record to a journal record is a key indication of creation date. Because Whitmer arranged the texts chronologically, the transition of the ledger record to a journal record approximates the time Whitmer began the book. One finds that the transition from ledger to journal record took place circa March to June 1831. In the first thirty-six revelations dated April 1829 to February 1831 (pages 12–70), the copying shows only two obvious disruptions in flow, style, and form—a strong hint that Whitmer was employing ledger-type record keeping for this portion. The next eleven revelations from March to June 8, 1831 (71–90), show six clear disruptions between revelations, more indicative of a journal record. However, something unexpected happens after June 1831: only three clear disruptions occur in the eleven revelations from June 14 to October 1831 (91–112), hinting that Whitmer returned to a ledger-type recording.

Why does the BCR shift back to a record with characteristics of copying many items at once during the summer to early fall of 1831? External evidence explains the apparent inconsistency. During the summer of 1831, Joseph Smith and others from Kirtland, Ohio, visited Missouri to strengthen the Church there and reveal the location of Zion. While in Missouri, Joseph Smith dictated a number of revelations, which were then copied into the volume by Whitmer. Because the historical record indicates that John Whitmer did not accompany the group to Missouri,22 he could not have copied the revelations into the manuscript volume until after the members of the group returned to Ohio in late summer of 1831—the date of the first revelation of the next ledger-style record. Whitmer’s absence in Missouri necessitated “catching up” on revelation copying, and therefore the volume again displays the characteristics of a ledger record.

November brought the reception of eight more revelations copied into the BCR. Of these eight November revelations (113–125), seven obvious disruptions occur between revelations, indicating that this portion of the volume is clearly a journal record. While the current evidence does not—and possibly never will—definitively prove an 1831 creation date, the data strongly point to the conclusion that Whitmer first began work on the Book of Commandments and Revelations in the spring or early summer of 1831.

Provenance: Use

In the early part of March 1831, John Whitmer was called by revelation to “write & keep a regulal history, & assist my servent Joseph in Transcribing all things which shall be given.”23 By copying the revelations into the manuscript book, Whitmer would obviously be fulfilling the “transcribing” portion of the revelation, but the manuscript revelation book also appears to fit his calling as historian. Whitmer’s role as historian becomes apparent in the manuscript volume. The revelations bear historical headings providing immediate background for the reception of the revelations, thus placing these revelations in their historical context.24

The format Whitmer adopted to present the revelations within the BCR provides some clue to the original intent of the book. Even though the book was eventually used to print the revelations in Missouri and Ohio, its original purpose was not a printer’s manuscript from which to publish revelations—the decision to publish the revelations did not come until November 1831. Unlike the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon, the sole purpose of which seems to have been for use in the printing process, it appears that the manuscript revelation book was originally created as a comprehensive, clean-copy register of revelations in one volume.

The spring of 1831 as a likely creation date marks an important era in John Whitmer’s personal life. For most early revelations in the volume, Whitmer provided a title (usually “Commandment”), assigned a number (thereby ordering the revelations), and gave a date (at times quite generic). In somewhat fewer instances, Whitmer also gave a historical introduction explaining the immediate reception of the text. This format reveals much about the early Church’s record-keeping mentality and the views early Saints had about their sacred texts—a topic this paper can only briefly discuss. For instance, ordering texts chronologically and numbering those texts indicates an attempt to place the many revelations into a manageable whole—one which readers would find useful. The assignment of a title to each revelation suggests an attempt to categorize, familiarize, or otherwise understand the terminology placed upon these sacred texts. The attempt to date every item, even the most generic terms (“AD 1830”), might mean that Whitmer was attempting to place these texts in a chronological time frame. In the early days of the Church, Mormons were beginning to situate the revelations within their recent history and among the other sacred texts, and Whitmer was capturing this personal and churchwide scriptural fortification on paper. By stringing these documents together with brief bridge narratives, Whitmer was creating a documentary history, the format also used in the early portions of the Whitmer history and the final Joseph Smith history. The precise influence, if any, of the BCR on these and other works is unknown, but its status as a history should not be ignored.

John Whitmer continued to copy revelations into the volume in a chronological fashion throughout 1831. However, following the revelations received in November 1831, the book is not strictly chronological in nature—a fact with a rather practical explanation. The Book of Commandments and Revelations was now in Independence, Missouri, and it took months for the revelations, which were received by Joseph Smith in Kirtland, Ohio, to travel by mail or other carriers approximately one thousand miles to John Whitmer in Missouri. The time lapse began to affect the manuscript book not only through breaks in the copying, but also in the order of revelations. The revelations were not supplied to Whitmer constantly, and he copied them into the volume as time and means permitted. By this time, however, the volume was not simply used as a place to store revelations for reference in Missouri. A specific reason brought the BCR to the American frontier: publication.

In July 1831, Joseph Smith received a revelation that appointed William W. Phelps as printer to the Church, to be assisted by Oliver Cowdery (D&C 57:11–13).25 As with other early Mormon record-keeping efforts, the first consideration was to publish these revelations. In November 1831, a conference of the elders of the Church deliberated the issue of how to proceed. The attendees were not governed by caution; they decided to publish ten thousand copies of a book of revelations—twice the print run of the Book of Mormon.26 A council declared that the “book of Revelation” to be published would be “the foundation of the Church & the salvation of the world & the Keys of the mysteries of the Kingdom & the riches of Eternity to the Church.”27 The printed title page provides one glimpse of the purpose of the book: “A Book of Commandments, for the Government of the Church of Christ.” The notice of the revelation book in the Church newspaper told of another purpose: that the Church “may lift up their heads and rejoice, and praise his holy name, that they are permitted to live in the days when he returns to his people his everlasting covenant, to prepare them for his presence.”28 The revelatory preface to the published work contained the words of the Lord concerning the revelations’ import: “Search these commandments, for they are true and faithful, and the prophecies and promises which are in them, shall all be fulfilled. . . . For behold, and lo, the Lord is God, and the Spirit beareth record, and the record is true, and the truth abideth forever and ever: Amen.”29 The divine communications were meant to govern the millennial Church until the Savior’s return.

Oliver Cowdery (fig. 9), as assistant Church printer, was appointed by a council of leaders to take the “commandments and the moneys” with him to Missouri where a press would be established (D&C 69:1).30 The creator and custodian of the BCR was later commanded by revelation to accompany Cowdery.31 Before leaving, the council appointed Joseph Smith to “correct those errors or mistakes which he may discover by the holy Spirit while reviewing the revelations & commandments & also the fulness of the scriptures.”32 While the Book of Commandments and Revelations is replete with editorial markings, most served to modernize biblical language or clarify existing language, not to correct “errors or mistakes.” Joseph Smith’s volume of handwriting pales in comparison to Rigdon’s and Whitmer’s editorial changes. Smith likely delegated the responsibility of “correcting” to Rigdon, Whitmer, or Cowdery—or to all three. Despite Smith’s limited or nonextant effort to “correct” the revelations, in mid-November 1831 he “consecrate[d] these brethren [Cowdery and Whitmer] & the sacred writings . . . to the Lord,”33 and the pair carried the Book of Commandments and Revelations to Missouri to be used in the publication process.

In Missouri, Cowdery and Whitmer, with the help of Church printer William W. Phelps, published revelations in both The Evening and the Morning Star and the Book of Commandments. Every revelation but one (the latter portion of current D&C 42) printed in the Star is found in the BCR—many bearing editing marks (fig. 10). Every revelation but one (D&C 12) printed in the 1833 Book of Commandments is found in the manuscript revelation book—though fewer bear editing marks.

Two of the three people known to have worked on the publication of the 1833 Book of Commandments had previous, albeit perhaps limited, printing experience. William W. Phelps, the most experienced printer of early Mormonism, had previously been editor of several newspapers before joining the Church.34 Oliver Cowdery also had experience in setting type and helping produce the Book of Mormon at the Grandin print shop in Palmyra, New York.35 Although few primary sources describe the printing activity in Missouri, historians can reconstruct what likely occurred by comparing contemporary non-LDS printing practices and known Mormon printing practices. Such comparison yields an understanding of both the mechanical production and the cultural, social, and theological meaning the Latter-day Saints attached to printing.36 A thorough analysis of the printing of the Book of Commandments is beyond the scope of this article. Yet two questions with regard to the Book of Commandments and Revelations provide a focus into the printing operations of Missouri: First, how was the manuscript volume used in printing the Book of Commandments? And second, did the editors draw from other material when compiling or editing the printed revelations?

Establishing the when and how of the editorial emendations of the Book of Commandments and Revelations is an important step in understanding the volume’s use in the publication of revelations in Missouri. Rigdon’s handwriting in the majority of the Book of Commandments and Revelations was inscribed in Ohio in 1831, before the volume was carried to Missouri.37 Whitmer and Cowdery may have made some corrections in Ohio, but they had more time for reviewing the revelations while in Missouri. The heavy ink of William W. Phelps supplying verse numbers and punctuation accenting the BCR must have been done in Missouri as they were preparing for publication. A few trends in the actual editing of the text stand out. Whitmer often restored the original wording of many of the revelations that had been adjusted by Rigdon. For example, as originally recorded, a phrase out of current section 33 reads, “remember they shall have faith in me.” Rigdon altered the reading so that it read, “remember you must have faith in me.” Whitmer canceled Rigdon’s wording and wrote in “they shall” to revert the wording back to the original, which is as it reads today (D&C 33:12).38 Many similar examples fill the pages of the Book of Commandments and Revelations. This return to a conservative editing style might be explained by a letter Smith sent to Phelps wherein Smith counseled the Church’s printer to “be careful not to alter the sense of any of [the revelations] for he that adds or diminishes to the prop[h]ecies must come under the condemnation writen therein.”39 Smith must have felt trepidation at leaving the printing of sacred texts to others’ hands—no matter how capable those individuals might have been.

While the handwriting of later editors provides a necessary glimpse of how the BCR was used for subsequent printing, not every revelation eventually published in the printed book had been marked up in the manuscript book. For instance, current section 26 and the beginning of section 25 are found on the same page of the manuscript revelation book. Section 26 is edited with punctuation and versification, but once section 25 begins, all editing marks cease (fig. 11).40 Another example complicates the puzzle. The first several pages of current section 63 found on pages 104–8 of the BCR bear inserted punctuation and versification (through the middle of page 106) (fig. 12). The next two pages contain no added verses to the revelation, but the last five lines of the revelation have three verse numbers added (fig. 13).41 In fact, of the fifty-seven revelations published in the Book of Commandments that are also currently found in the BCR, twenty-six of them have no editorial versification added in the BCR.42 If the editors of the Book of Commandments were being consistent in preparing the manuscript texts with punctuation and versification, then there must have been other copies of revelations to work with in the Missouri print shop. The editors clearly accessed multiple sources from which to provide material for the printed edition of the revelations. For instance, current section 12 is not found anywhere in Whitmer’s revelation book, but it is found as chapter 11 in the Book of Commandments. Now that a significant source of the printing effort in Missouri is available, scholars can make an in-depth study of that publishing history.

As mentioned earlier, the original volume was a bound blank book, but the volume was at some point disassembled—likely done purposely. The outer boards of the volume are no longer extant; instead, a heavy piece of cardstock paper encloses the volume’s pages. Several pages are missing from the volume held at the LDS Church History Library; some of them are held at the Community of Christ Library-Archives, and others are nonextant. Other pages bear clear marks indicating they were cut from the volume but are currently still housed within the volume. It appears that pages cut or torn from the volume were removed but then reinserted, where most remain today. The edges of many of these reinserted pages appear worn, but they do not appear to have been through damage such as the destruction of the printing office at Independence in 1833. The current paperboard cover contains pinholes along the spine that match up to holes and a piece of thread found in remnants of the fifth gathering of pages. The sewing would have been done to attach the cover to the volume by fixing it to a middle (in this case, the fifth) gathering. Keeping the fifth gathering between the other gatherings would in turn preserve the cover around all the gatherings. However, the pages from the fifth gathering were later cut and are currently loose, rendering the makeshift attachment of the cover obsolete. All these patterns of use—disassembling covers, then protecting the volume with a temporary cover, and then again cutting pages from the fifth gathering—indicate gradual disassembling of the volume rather than a one-time, abrupt removal of the boards and inside pages.

There are several possibilities as to when the volume was taken apart. Either in Missouri or in the printing of the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants in Kirtland (or both), the printers might have separated some of the leaves from the volume in order to set type from one sheet rather than having to handle a bulky and heavy two-hundred-page manuscript book. The missing leaves (both nonextant and those at the Community of Christ Library-Archives) were probably not permanently separated from the book until after the 1835 publication process. This is confirmed by the fact that one of the separated pages held at the Community of Christ Library-Archives has notations for the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants publication. This 1835 notation is similar to several other notations on the extant pages within the volume. So if the pages were separated in Missouri, they were likely reinserted before Ohio and then separated again after Ohio. While this intricate scenario remains a possibility, a one-time removal of the pages after the Ohio publication would compel a less complex set of assumptions.

Following the forced abandonment of publication of the Book of Commandments in 1833, the whereabouts of the BCR can only be surmised through available sources and historical events. Custodianship likely remained with those involved with the printing of the Book of Commandments: John Whitmer, Oliver Cowdery, and William W. Phelps. Because Whitmer continued to update the volume as late as summer 1834, we can safely assume that it was he and not Phelps or Cowdery who continued to possess and create portions of the volume. In fact, the BCR was continually updated in Missouri, likely making it the most comprehensive register for the Missouri church and certainly the most complete collection of manuscript revelations currently extant. By 1834, no more revelations were copied into the manuscript volume because the volume was full. When Cowdery began work on the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants with others in Kirtland, it is evident that he did not have access to the BCR—the volume was likely still with John Whitmer in Missouri.43 Whitmer did not come to Ohio until 1835—just months before the printed Doctrine and Covenants became available to the public. The printing of the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants, like the Book of Commandments, should be discussed elsewhere in depth; this paper will only focus on the BCR’s minor role in the 1835 printing project.44

Unlike the numerous redactions made for the publication of the Book of Commandments, those additions to the manuscript text for the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants publication are limited. Oliver Cowdery, Frederick G. Williams, Joseph Smith, and others who worked on the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants used other printed and manuscript versions of the revelations, including the Kirtland Revelation Book and the Book of Commandments. Redactions in the BCR correspond to lengthy additions found in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants. These include the use of asterisks and pinholes found in the manuscript near the place of addition. Neither of these methods contained the actual text to be added, but likely alerted copyists or typesetters where to include the text that was on a separate piece of paper, either pinned directly to the text or found elsewhere. Similarly, several revelations bear markers over proper nouns replaced in the 1835 publication with code names.45 Often revelations identified individuals simply by their first names; last names are inserted in many cases throughout the BCR that were then incorporated into the 1835 publication. A few revelations bear paragraph or verse markers, and word changes were occasionally made for the 1835 publication. On the whole, the BCR played a supplementary role in the publication of the 1835 Doctrine in Covenants, though still an important one.

Provenance: Chain of Custody

Following the publication of the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants, the Book of Commandments and Revelations remained obscure for quite some time. The volume itself can be used to determine the chain of custody through 1835, when Whitmer and others ceased writing in the volume. It is unknown who possessed the volume from the Kirtland period until the Saints settled in Nauvoo, Illinois. Based on the likely custody of other similar records, perhaps Whitmer or Cowdery retained the volume, but they both left the Church in 1838 and would likely have retained possession of it, as Whitmer did with his copy of the Joseph Smith Bible revision manuscript and as Cowdery did with the printer’s copy of the Book of Mormon manuscript. Phelps might have retained the volume and returned it to the Church when he returned to church activity in Nauvoo. Another scenario perhaps more likely is that Joseph Smith and his scribes held custody of the volume until Smith’s death in 1844.

There is a possible reference to the volume in the 1846 inventory of Church documents made previous to the exodus: “Rough Book – Revelation History &c.”46 If this inventory entry indeed refers to the Book of Commandments and Revelations, it means that the volume came with the Saints to Utah in 1847 with the other documents of historical importance. The boxes containing historical material were unpacked in Utah beginning on June 7, 1853.47 The BCR is known to have been in the Church Historian’s Office by the mid-1850s, when Leo Hawkins (a historian’s office employee from 1853 through 1856) provided a label to the spine of the cover; the volume was likely with the other historical material at that time. The compilers of the Joseph Smith history in Nauvoo and Utah, if they had access to the volume, used the volume randomly and modestly to correct or add dates to otherwise undated revelations.48

Thomas Bullock transcribed two copies of the prophecy on wars given to Joseph Smith on December 25, 1832 (D&C 87) in the mid-1850s from the Book of Commandments and Revelations.49 Based on a discourse he gave in 1855, Orson Pratt seemed to have seen the BCR’s copy of the “pure language” document or a copy similar to it.50 Two inventories of the Church Historian’s Office historical material, dated 1858 and 1878, list the Book of Commandments and Revelations by title.51 B. H. Roberts, in compiling what would become the Comprehensive History of the Church, did not appear to know about the text of the Canadian copyright revelation when he provided commentary of that episode in his history.52 About the same time Roberts was compiling his history, another prominent individual at the Church Historian’s Office, Andrew Jenson, also seemed unaware of the existence of the volume. An entry in the Journal History, dated November 3, 1831, reads, “The Book of Commandments and Revelations was to be dedicated by prayer.”53 Jenson wrote in the margin “Wrong” and underlined the words “Book of Commandments,” apparently not knowing of the existence of a manuscript with the title of “Book of Commandments and Revelations.”

That two prominent figures in the Church Historian’s Office did not seem to know about the BCR at the turn of the twentieth century corresponds to the fact that another prominent individual likely did. Joseph Fielding Smith wrote a letter in 1907 and hinted at knowing about the source used to print the Book of Commandments.54 Because the Book of Commandments and Revelations is listed on a 1970 inventory of the Joseph Fielding Smith safe, the question is not if the manuscript ended up in Joseph Fielding Smith’s papers, but when.55 Smith served as Church historian and recorder and also served in the Quorum of the Twelve and First Presidency—all offices that exact considerable demands. If the BCR remained in the personal possession of Joseph Fielding Smith early on, and if the manuscript was unknown to others, this would explain the manuscript’s absence in the twentieth century historiography.56

The pages now held by the Community of Christ have their own history once they were separated from the volume. The pages were likely separated before John Whitmer or Oliver Cowdery’s excommunication from the LDS Church in 1838. A secondhand source states that the leaves were held by Oliver Cowdery until he gave them to David Whitmer just before Cowdery’s death in 1850.57 However, the leaves were grouped with other papers held by John Whitmer (including the Book of John Whitmer and the copy of the Joseph Smith Bible revision), possibly indicating that the leaves were in Whitmer’s possession until his death in 1878.58 Regardless, the pages transferred to David Whitmer eventually came into the possession of George Schweich, David Whitmer’s grandson-in-law. Schweich sold these pages to the RLDS Church, where they have remained ever since. Now these pages, along with the volume from which they were separated, have been published in the Revelation and Translation series of the Joseph Smith Papers, allowing historians and interested readers unprecedented access to the revelation texts of Joseph Smith.

The important Book of Commandments and Revelations had a quiet beginning, an important and convoluted printing history, and just as quiet a retirement. The publication of this manuscript volume provides scholars with unparalleled access to earlier and unknown revelation texts, a better understanding of the revelatory publication process, more insight into the revelatory record-keeping practices, and a richer understanding of the changes of the revelation texts. When scholars approach the volume not simply as a register of important religious texts for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but also as an artifact with the potential to exhibit the attitude early Latter-day Saints held toward their sacred texts, they can understand more than just the texts. The Mormons painstakingly copied, published, and incorporated the revelation texts into their lives. John Whitmer did remarkable work in transcribing the revelations of Joseph Smith and keeping a record or history for future use by today’s generations. Thus a clearer understanding of the Book of Commandments and Revelations comes through a proper study of its provenance, history, and use, and such an understanding will bring scholars face to face with the seriousness with which Mormons approached their religious texts—as texts to copy, as documents to publish, as a foundation upon which to build and spread the gospel, and, most importantly, as revelations that gave them directions from God.

About the author(s)

Robin Scott Jensen is coeditor of volume three in the Journals series and volume one in the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers. Jensen wishes to express his gratitude to many individuals on the Joseph Smith Papers Project and elsewhere who gave their time to discuss matters relating to the BCR and who read earlier drafts of this paper. Especially helpful were Christy Best, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Jeffery O. Johnson, Ronald K. Esplin, Dean C. Jessee, Nathan N. Waite, Glenn Rowe, Ronald Romig, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper. Thanks also to Emily W. Jensen, who carefully read and commented on earlier drafts of this paper.

Notes

1. Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper, eds., Manuscript Revelation Books, facsimile edition, first volume of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2009).

2. Book of Commandments and Revelations, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah, 30–31, 144. Several reminiscent accounts of the Canadian copyright revelation by those close to the event have provided sources for historians for many years. See Hiram Page to William E. McLellin, February 2, 1848, Library and Archives of the Community of Christ, Independence, Missouri, hereafter Community of Christ Library-Archives; David Whitmer, An Address to All Believers in Christ by a Witness to the Divine Authenticity of the Book of Mormon (Richmond, Mo.: By the author, 1887), 30–32; William E. McLellin to Joseph Smith III, July 1872, Community of Christ Library-Archives; and William E. McLellin Notebook, John L. Traughber Collection, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. For several scholarly discussions, see B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Century One, 6 vols. (Provo, Utah: Corporation of the President, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1965), 1:162–66; Marvin S. Hill, Quest for Refuge: The Mormon Flight from American Pluralism (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1989), 20; and Richard E. Bennett and Daniel H. Olsen, “Of Printers, Prophets, and Politicians: William Lyon Mackenzie, Mormonism, and Early Printing in Upper Canada,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: Ohio and Upper Canada, ed. Guy L. Dorius, Craig K. Manscill, and Craig James Ostler (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, 2006), 177–208. For the reference to the pure language document, see Orson Pratt, “The Holy Spirit and the Godhead” in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1855–86), 2:342 (February 18, 1855).

3. The Society of American Archivists define provenance as “1. The origin or source of something. – 2. Information regarding the origins, custody, and ownership of an item or collection.” Richard Pearce-Moses, ed., A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2005), s.v. “provenance,” available at www.archivists.org/glossary.

4. The Society of American Archivists defines content as “the intellectual substance of a document, including text, data, symbols, numerals, images, and sound.” Context is defined as “the organizational, functional, and operational circumstances surrounding materials’ creation, receipt, storage, or use, and its relationship to other materials.” Pearce-Moses, Glossary, s.v. “content” and “context.”

5. See, for example, the account of a visit to David Whitmer by Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith: “According to the best of his [Whitmer’s] knowledge, there never was but the one copy.” Deseret News, November 16, 1878, quoted in Lyndon W. Cook, ed., David Whitmer Interviews: A Restoration Witness (Orem, Utah: Grandin Book, 1991), 44. James H. Hart recalls an interview with Whitmer: “I remarked that [the manuscript] looked very much as though it was the original copy, and it would in fact take considerable more evidence than I had seen to convince me that it was not the original and only written copy.” Hart continued, “Mr. Whitmer said, ‘I know, positively, that it is so.’” Deseret News, March 25, 1884, quoted in Cook, David Whitmer Interviews, 111.

6. See Lavina Fielding Anderson, Lucy’s Book: Critical Edition of Lucy Mack Smith’s Family Memoir (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2001), 459, for the revelation Joseph Smith received to make a second copy of the Book of Mormon manuscript.

7. See Royal Skousen, “John Gilbert’s 1892 Account of the 1830 Printing of the Book of Mormon,” in The Disciple as Witness: Essays on Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine in Honor of Richard Lloyd Anderson, ed. Stephen D. Ricks, Donald W. Parry, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2000), 383–405; and Royal Skousen, “The Book of Mormon Critical Text Project,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, the Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, 1993), 65–75.

8. From December 10, 1830, through March 7, 1831, JS dictated the majority of Old Testament manuscript 1. Scott H. Faulring, Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds., Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, 2004), 63–64.

9. Royal Skousen, ed., The Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon: Typographical Facsimile of the Extant Text (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2001); and Royal Skousen, ed., The Printer’s Manuscript of the Book of Mormon: Typographical Facsimile of the Entire Text in Two Parts, 2 vols. (Provo, Utah: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2001).

10. Most of these documents could be considered religious, or at the very least devotional, but not scriptural. My count of manuscript pages includes the following documents: The “Caractors” document commonly known as the Anthon Transcript (Community of Christ Library-Archives); two land transactions between Smith and his father-in-law, Isaac Hale (both held in the Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library); the copyright registration form for the Book of Mormon (Joseph Smith’s retained copy is now in the Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library); and the preface to the Book of Mormon (found in Skousen, Printer’s Manuscript, 1:50–51); Letters to Oliver Cowdery, October 22, 1829 (Joseph Smith Letterbook, 1:9, in Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library), the Colesville saints, August 20, 1830, and December 2, 1830 (both as copied into the Newel Knight Autobiography, private possession), Martin Harris, February 22, 1831 (Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library), and Hyrum Smith, March 3, 1831 (Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library); a financial agreement with Martin Harris (Gratz Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Penn.); five ecclesiastical licenses to John Whitmer, Christian Whitmer (both at Beinecke Library, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.), Joseph Smith Sr. (Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library), Edward Partridge (Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library), and William Smith (Community of Christ Library-Archives); and a signed missionary covenant (as copied in Ezra Booth to Ira Eddy, November 29, 1831, as printed in “MORMONISM – NOS. VIII – IX,” Ohio Star, December 8, 1831). Five of these documents are actually copies of the original; thus the tally of the original, extant documents is even less than the total provided. The Joseph Smith Papers Project will publish these documents in the Documents series, volume 1. A few pages of minutes also exist, but they were not included in this tally, as they were not created exclusively by Smith.

11. “Church History,” Times and Seasons 3 (March 1, 1842): 707.

12. The Kirtland Revelation Book is held in the Revelation Collection in the Church History Library; the 1832 history is contained in the first Joseph Smith letterbook, which, along with the journal, is housed in the Joseph Smith Collection in the Church History Library. The minute book is also held at the Church History Library.

13. For instance, section 5 of the current Doctrine and Covenants was created by Oliver Cowdery shortly after the reception of the original revelation on two loose leaves (Newel K. Whitney Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Provo, Utah). The Edward Partridge copies of revelations held in the Church History Library have evidence of previously being hand-sewn. For discussion of the sewing of the Book of Mormon manuscript, see Skousen, Original Manuscript, 34; and Skousen, Printer’s Manuscript, 1:31–32.

14. Joseph Smith History, 50, as found in The Papers of Joseph Smith, ed. Dean C. Jessee, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 1:259, 319.

15. Luciana Duranti, Diplomatics: New Uses for an Old Science (Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 1998).

16. Luciana Duranti and Maria Guercio, “Definitions of Electronic Records: Research Issues in Archival Bond,” from Electronic Records Meeting, held in Pittsburgh, Pa., on May 29, 1997, available online at http:/www.archimuse.com/erecs97/s1-ld-mg.HTM (accessed October 22, 2007).

17. As a leading scholar of archival diplomatics puts it, diplomatics “studies the genesis, forms, and transmission of archival documents, and their relationship with the facts represented in them and with their creator, in order to identify, evaluate, and communicate their true nature.” Duranti, Diplomatics, 45.

18. Pearce-Moses, Glossary, s.v. “form” and “structure.”

19. There are many copying errors—including those due to homeoarchton or homeoteleuton leading to skipping or repeating text—throughout the BCR. This indicates that very few if any entries are dictated copies of revelations.

20. Of course, this explanation makes an assumption about the connection of the dating of revelations with the BCR; the connection could instead be a reflection of the texts from which Whitmer copied. In other words, as Smith received more and more revelations, the scribes capturing the scriptural texts might have been better at capturing the date of the texts. This would be reflected in the manuscript volume without Whitmer’s immediate involvement or effort. Thus rather than interpreting the transition of the dates in the revelation manuscript as evidence of an early 1831 dating, the interpretation may be a development of a better record-keeping culture. However, evidence favors some (although not a perfect) correlation between dates found in the BCR and the creation of the volume itself. Whitmer, from almost the beginning of the volume, created a focus of historical context before each revelation. Even when only the year of the revelation’s reception was known, Whitmer provided that seemingly unhelpful information as part of the format or model of copying in this book. He must have had more specific dates in mind when he began to copy (or supply) the nonspecific dates into the beginning of the volume.

21. See, for example, the Kirtland Revelation Book, 11. Doctrine and Covenants 71, received December 1, 1831, was copied in the Kirtland Revelation Book as being received “Dec. 1st 1832.” The copying likely took place in March 1832.

22. Of the several sources outlining the summer 1831 visit to Missouri, none mention John Whitmer. There are no sources documenting Whitmer in Ohio, either, but no clear sources survive for that period in Ohio. In Whitmer’s own history, he resorts to quoting from Cowdery’s account of the Missouri trip, indicating that Whitmer was not there himself to recollect the events. “The Book of John Whitmer,” 31–33, Community of Christ Library-Archives.

23. Revelation, circa March 8, 1831, as found in Book of Commandments and Revelations, 79 (D&C 47).

24. It seems Whitmer also added summaries of the chapters of the Bible revision he worked on with Joseph Smith. For instance, several headings were added to Old Testament Manuscript 2 that are not found in Old Testament Manuscript 1, showing that Whitmer might have added additional text in the heading when copying the revelations into the BCR. See Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation, for the transcript of the Bible revision done by Joseph Smith.

25. Book of Commandments and Revelations, 93–94. Doctrine and Covenants 58:37 directed the purchase of land for a store and print shop in Independence.

26. Minutes of meeting dated November 1, 1831, copied into “The Conference Minutes, and Record Book, of Christ’s Church of Latter Day Saints,” transcript available in Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., Far West Record: Minutes of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1844 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 27.

27. Minutes of meeting dated November 12–13, 1831, copied into “Conference Minutes, and Record Book,” in Cannon and Cook, Far West Record, 32.

28. “Revelations,” The Evening and the Morning Star 1 (May 1833): 89.

29. A Book of Commandments, for the Government of the Church of Christ, Organized According to Law, on the 6th of April, 1830 (Independence, Mo.: W. W. Phelps, 1833), 6.

30. This revelation seems to indicate that Cowdery had already been appointed before this revelation. The Joseph Smith history supports this conclusion; the revelation copied therein is preceded with this explanation: “It had been decided by the conference that Elder Oliver Cowdery should carry the commandments and revelations to Independence, Missouri, for printing, and that I should arrange and get them in readiness by the time that he left.” Jessee, Papers of Joseph Smith, 1:368. Book of Commandments and Revelations, 122.

31. Revelation, November 11, 1831–A, in Book of Commandments and Revelations, 122 (D&C 69:2).

32. Minutes of meeting dated November 8, 1831, copied into “Conference Minutes, and Record Book,” in Cannon and Cook, Far West Record, 29. The reference to the “fulness of the scriptures” might hint at the desire of Joseph Smith to publish the Bible revision. See Ronald E. Romig, “The New Translation Materials since 1844,” in Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation, 29–40.

33. Minutes of meeting dated November 12–13, 1831, copied into “Conference Minutes, and Record Book,” in Cannon and Cook, Far West Record, 32.

34. See Walter Dean Bowen, “The Versatile W. W. Phelps—Mormon Writer, Educator, and Pioneer” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1958); and Bruce A. Van Orden, “‘By That Book I Learned the Right Way to God’: The Conversion of William W. Phelps,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: New York, ed. Larry C. Porter, Milton V. Backman Jr., and Susan Easton Black (Provo, Utah: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1992), 202–13.

35. Cowdery wrote to Smith in late December 1829, “It may look rather strange to you to find that I have so soon become a printer.” Oliver Cowdery to Joseph Smith, December 28, 1829, Joseph Smith Letterbook 1:5, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library. See also the printers’ recollection of Cowdery’s role: He “was not engaged as compositor on the work or was not a printer. He was a frequent visitor to the office, and did several times take up a ‘stick’ and set a part of a page—he may have set 10 or 12 pages, all told—he also a few times looked over the manuscript when proof was being read.” John H. Gilbert to James T. Cobb, February 10, 1879, Theodore A. Schroeder Papers, New York Public Library, quoted in Early Mormon Documents, ed. Dan Vogel, 5 vols. (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), 2:523.

36. For an excellent survey of the historical, non-Mormon context of early Mormon printing practices with an endeavor to understand the cultural implications, see David J. Whittaker, “The Web of Print: Toward a History of the Book in Early Mormon Culture,” Journal of Mormon History 23, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 1–41. For a study of Book of Mormon printing and publication, see Richard Lloyd Anderson, “Gold Plates and Printer’s Ink,” Ensign 6 (September 1976): 71–76; Larry C. Porter, “The Book of Mormon: Historical Setting for Its Translation and Publication,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, the Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, 1993), 49–64; Royal Skousen, “Translating and Printing the Book of Mormon,” in Oliver Cowdery: Scribe, Elder, Witness, ed. John W. Welch and Larry E. Morris (Provo, Utah: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2006), 75–122, esp. 101–16. A discussion of the printing of the Book of Commandments begins with Ronald E. Romig and John H. Siebert, “First Impressions: The Independence, Missouri, Printing Operation, 1832–33,” in The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 10 (1990): 51–66; and Robert J. Woodford, “Book of Commandments,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 4 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1:138. The 1835 publication of the Doctrine and Covenants has garnered very little attention by way of scholarly works; for a general discussion of the publication of the revelations, see Robert J. Woodford, “The Historical Development of the Doctrine and Covenants” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1974); and H. Michael Marquardt, The Joseph Smith Revelations: Text and Commentary (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1999). For Joseph Smith–era Mormon printing in general, see the bibliographic studies of Chad J. Flake and Larry W. Draper, A Mormon Bibliography 1830–1930: Books, Pamphlets, Periodicals, and Broadsides Relating to the First Century of Mormonism, 2nd ed., rev. and enl. (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, 2004); and Peter Crawley, A Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 2 vols. (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1997), 1:1. Other works include David J. Whittaker, Early Mormon Pamphleteering (Provo, Utah: Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Latter-day Saint History, 2003); and Terence A. Tanner, “The Mormon Press in Nauvoo, 1839–46,” in Kingdom on the Mississippi Revisited: Nauvoo in Mormon History, ed. Roger D. Launius and John E. Hallwas (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 94–118.

37. John Whitmer copied sections 20 and 42 into Zebedee Coltrin’s journal on January 12, 1832, one week after Whitmer and Cowdery’s arrival in Missouri on January 5, 1832 (Zebedee Coltrin Journal and John Whitmer Account Book, Church History Library). The Coltrin versions incorporate the Sidney Rigdon emendations which are in the BCR, meaning that Rigdon had made changes for at least two revelations by that time. Because Rigdon’s presence in Missouri was limited, it can be assumed that the majority of his editing marks were in place before the volume went to Missouri in late 1831.

38. Book of Commandments and Revelations, 45.

39. Joseph Smith to William W. Phelps, July 31, 1832, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library.

40. Book of Commandments and Revelations, 34.

41. Another example is found on page 28, where verse 41 is inserted after a previously clean text.

42. It should be remembered that seven revelations were once found in the Book of Commandments and Revelations but are now missing. Current Doctrine and Covenants 12 was not copied into the manuscript book. There were a total of 65 revelations (the final revelation only partially complete) printed in the Book of Commandments.

43. Oliver Cowdery requested of Newel K. Whitney a copy of modern-day Doctrine and Covenants 42 in his preparation to reprint the Evening and Morning Star. Oliver Cowdery to Newel K. Whitney, February 4, 1835, Newel K. Whitney Collection, Perry Special Collections). Oliver Cowdery left Missouri about July 26, 1833 (Manuscript History of the Church, A-1, 330, Church History Library), and arrived in Ohio August 9 (Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith to “Dear Brethren,” August 10, 1833, Church History Library).

44. Unfortunately, few scholarly works address the 1835 publication of the Doctrine and Covenants. See the brief mentions in Woodford, “Historical Development of the Doctrine and Covenants”; Marquardt, Joseph Smith Revelations; and Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography, vol. 1.

45. For information about these code names, see David J. Whittaker, “Substituted Names in the Published Revelations of Joseph Smith,” BYU Studies 23, no. 1 (Winter 1983): 103–12.

46. Church Historian’s Office inventory, 1846, Church History Library.

47. Church Historian’s Office Journal, Church History Library.

48. For instance, the Joseph Smith history reproduces four revelations (now sections 39, 40, 60, and 133) that match the exact dates found in the BCR, dates not found on any other extant manuscript (including minutes of meetings). However, sections 48–59 and 61–70 are precisely dated in the BCR, but these dates were not carried over to the Joseph Smith history. It is possible that the compilers of Joseph Smith’s history were using other revelation manuscripts now nonextant.

49. The two copies of Doctrine and Covenants 87 are found in the Revelation Collection, Church History Library.

50. Pratt, “The Holy Spirit and the Godhead,” 2:342. Four months previous to this discourse, Pratt “called [and] examined some old documents & revelations” at the Historian’s Office. Church Historian’s Office Journal, October 20, 1854, Church History Library.

51. “Contents of the Historian and Recorder’s Office,” [5]; “Index Records and Journals in the Historian’s Office 1878,” [5], Catalogs and Inventories, 1846–1904, Church History Library.

52. B. H. Roberts, “History of the Mormon Church,” Americana 4, no. 9 (Dec. 1909): 1016–25. Also available in Roberts, Comprehensive History, 1:157–66.

53. Journal History of the Church, November 3, 1831, 5, Church History Library, microfilm copy in Harold B. Lee Library. This entry is simply a page cut and pasted from the November 1831 conference found in History of the Church, 1:234.

54. In answering a question regarding early revelation record keeping, Joseph Fielding Smith wrote: “The revelations when first given were written on ordinary sheets of paper, generally foolscap, and were afterwards compiled and recorded in the bound records of the Church by, or under the direction of, Joseph Smith the Prophet, who took great care to have them correct. These records are now in the possession of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” He continued, “If you desire to compare the manuscript records with the Book of Commandments as that book was fragmentarily published in Independence, a trip to Salt Lake City for that purpose would be almost a waste of time as I can assure you that the manuscript agrees with the revelations as published and revised by the Prophet in 1835, and which have been published in the several editions of the Doctrine & Covenants since that time.” Joseph Fielding Smith to John R. Haldeman, May 24, 1907, Joseph Fielding Smith Collection, Church History Library.

55. “Inventory of President Joseph Fielding Smith’s Safe,” May 23, 1970, Church History Library.

56. To many, the long absence of the Book of Commandments and Revelations might be startling considering the important revelatory textual versions contained therein. However, one must recognize not only the extremely busy schedule of the First Presidency of the LDS Church in the past century, but also consider that the notice, interest in, or in-depth study of the BCR likely has only just developed. Until recently the study of textual variants—or even the interest in manuscript sources of printed texts—by the public at large has been largely relegated to those in academia. This is made quite clear by Joseph F. Smith’s answer to someone offering the Book of Mormon printer’s manuscript to the LDS Church: “It has been repeatedly offered to us . . . but we have at no time regarded it as of any value, . . . and as many editions of the Book of Mormon have been printed, and tens of thousands of copies of it circu[l]ated throughout the world you can readily perceive that this manuscript really is of no value to anyone.” Joseph F. Smith to Samuel Russell, March 19, 1901, Perry Special Collections.

57. Former RLDS Church historian Walter W. Smith, who was present when these papers were turned over to the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, heard from both George Schweich and David Whitmer’s family that the leaves were “received by David Whitmer from Oliver Cowdery at his death in 1850.” Walter Smith to the RLDS First Presidency, Sept. 14, 1925, Community of Christ Library-Archives; see also Walter Smith to R. L. Fulk, December 13, 1919, Community of Christ Library-Archives.

58. Walter W. Smith noted on two different occasions that “these pages [of revelations] . . . were in the Whitmer manuscript book [Book of John Whitmer] and were the same that [George] Schweich turned over to the [RLDS] church.” Walter Smith to S. A. Burgess, April 15, 1926; see also W. Smith to the RLDS First Presidency, September 14, 1925, Community of Christ Library-Archives.

- Introducing A Book of Commandments and Revelations, a Major New Documentary “Discovery”

- From Manuscript to Printed Page: An Analysis of the History of the Book of Commandments and Revelations

- Historical Headnotes and the Index of Contents in the Book of Commandments and Revelations

- Revelation, Text, and Revision: Insight from the Book of Commandments and Revelations

- Response to the Book of Commandments and Revelations Presentations

- Spiritualized Recreation: LDS All-Church Athletic Tournaments, 1950–1971

- Eliza R. Snow’s Poetry

Articles

- Book of Mormon Stories That Steph Meyer Tells to Me: LDS Themes in the Twilight Saga and The Host

- Joseph Smith Papers, Journals, Volume 1: 1832–1839

- Joseph Smith Papers, Journals, Volume 1: 1832–1839

- Leonard J. Arrington: A Historian’s Life

- Matters of the Mind: Latter-Day Saint Helps for Mental Health

- Against the Grain: Christianity and Democracy, War and Peace

- Making Space on the Western Frontier: Mormons, Miners, and Southern Paiutes

- Constantine’s Bible: Politics and the Making of the New Testament

- Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction

- Polygamy on the Pedernales: Lyman Wight’s Mormon Villages in Antebellum Texas, 1845 to 1858

- Happy Valley

Reviews

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X