All Abraham’s Children

Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage

Review

Armand L. Mauss. All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage.

Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Like many members today, early members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints considered themselves to be of the House of Israel. According to Armand L. Mauss, an emeritus professor of sociology from Washington State University, this identity affected the relationship that members of the Church had with other groups, primarily Native Americans, Jews, and those of African descent. These changing and expanding relationships are the topic of his most recent book, All Abraham’s Children.

Perhaps the best chronicler of minority relationships in the LDS Church, Mauss examines the extensive historical record through a sociological lens. His documentation is likely the best of any researcher examining these issues today. Most readers will find the history of these views to be much more complicated, contradictory, and even conflicted than they might have imagined. Mauss’s recounting of the history is both insightful and unsettling.

Mauss employs several themes throughout the book. The preeminent one is how members of the Church formulated their own identity and how that identity changed as a result of missionary efforts of the Church and in response to historical conditions. Mauss argues that early Church members adopted the racialist thinking prevalent in nineteenth-century America and incorporated it into Mormon folklore to explain the ancestry of various groups. The thinking was spawned by three elements: British Israelism (the notion among the British that they were part of the House of Israel), Anglo-Saxon triumphalism, and LDS understanding of premortal life. For Mormons, the “chosen peoples” became those who accepted the gospel, those who possessed the “believing blood” of Israel (2–3, 22–23).

Church leaders’ views have not remained static, however. Mauss argues, and I think rightfully so, that leaders initially perceived the Church’s mission as gathering the children of Israel. Only later did leaders shift to the more universalistic view that the mission of the Church is to bring the gospel to all peoples of the world, to all who hear the Shepherd’s voice. Further, Mauss argues, the change was a “consequence of and concomitant with the spread of the Mormon missionaries and membership to increasingly ‘exotic’ parts of the world” (32).

Mauss provides an excellent summary of the contorted and erratic federal policies toward Native Americans. As with the federal policies, proselyting efforts by the Church and education of Indians at Brigham Young University were sporadic and uneven. Much of LDS effort in the middle of the twentieth century coincided with President Spencer W. Kimball’s interest in the welfare of Native Americans. He emphasized the Indian Seminary Program, the Indian Placement Program, and Native American enrollment at BYU. While the education of Indians at BYU was considered a great success by the U.S. Department of Education, graduation rates were still below those of other students at BYU. As LDS missionaries experienced increased success in Mesoamerica and South America, Mauss explains, the Church’s efforts to help the descendants of the Book of Mormon peoples shifted away from American Indians to these other populations. Mauss’s history of Native American education, both federal and within the purview of the Church, alone makes the book a worthy read for those who are not familiar with this history.

Using the emphasis on identity, Mauss explores how Mormon converts from minority communities within the United States make sense of their world and the bonds that often draw them back to their native communities. Being a good Church member and being Navajo or African American poses dilemmas and conflicts that few Anglo converts experience. Further, Mauss notes that identity conflicts for LDS converts in other countries (such as Mexico, Peru, or Brazil) are less salient. Converts in those countries can still be Guatemalan or Mexican or hold other national identities at the same time they are Mormon. Being Mormon and a minority in the United States, however, presents numerous conflicts since these individuals already have strong identities as members of a minority group. Many members of the Church fail to understand how strong the bonds to native communities are.

Another group that Mormons have always had an unusual relationship with is the Jews, the second minority group that Mauss discusses. In one chapter Mauss presents the history of the relationship between the LDS Church and the Jews, and in another he presents strong evidence, some from his own research dating back to the 1960s, that anti-Semitism has always been lower in the LDS Church than in the general population. As Mauss notes, “A special Mormon sympathy for the Jews developed as part of the emerging understanding among Anglo-Mormons . . . that they were themselves actually descendants of Ephraim and thus shared Israelite ancestry with the Jews” (164).

Mauss also devotes two chapters to the issue of blacks and the priesthood. The first chapter is on the early history. Some may be surprised to learn that a few African Americans were given the priesthood during Joseph Smith’s time. The second chapter details the changes that led to the priesthood revelation in June 1978. Here Mauss is particularly good at summarizing from extant writings and personal interviews how African-American members deal with conflicted identities and the anguish that some experience when offended by others within the Church. Mauss points to another source of conflict for black members: some in the Church still hold to archaic racial teachings as explanations for the priesthood denial. The fact that these views remain in extant Church-related literature is a primary concern to Mauss, and he writes in several places throughout the book about the issue.

Mauss acknowledges that Elder Bruce R. McConkie modified his views and writings about race and priesthood after the 1978 revelation. I find that McConkie’s revision is most evident in a talk he gave shortly after the announcement:

There are statements in our literature by the early brethren that we have interpreted to mean that the Negroes would not receive the priesthood in mortality. I have said the same thing. . . . It is time disbelieving people repented and got in line and believed. . . . Forget everything that I have said, or what President Brigham Young or President George Q. Cannon or whosoever has said in days past that is contrary to the present revelation. We spoke with a limited understanding and without the light and knowledge that has now come into the world.1

Further, in 1979 Elder Howard W. Hunter specifically addressed the notion of a favored-blood lineage in the Church. He declared that race, color, or nationality make no difference, for “‘we are all of one blood’ and children of the same God” (36).2 Yet faulty explanations for the priesthood ban continue to circulate among Church members and in some publications. Mormons who proffer these explanations simply fail to understand how hurtful they are to black members of the Church.

In the end, I think Mauss is optimistic about the future of race relations in the Church. He genuinely applauds President Gordon B. Hinckley’s outreach to minorities and public statements decrying racism. President Hinckley spoke about this issue in the priesthood session of the April 2006 general conference, but he made similar statements before the NAACP chapter meeting in Salt Lake City in the late 1990s.3

Some in the Church want minorities to disregard their groups of origin. This they cannot do. But eventually white members will accept a more diverse membership and allow minorities to be both black and Mormon, or both Native American and Mormon. Despite the previous priesthood ban, members of the LDS Church appear to be no more prejudiced toward minority groups than American society generally. Data from the General Social Survey, a nationally representative survey begun in 1972 and continuing through the present,4 and Mauss’s own early research5 show this. I suspect that the comments of President Hinckley and others will make a difference. Church members do listen to the prophet. And where the LDS population is diverse, members meet, worship, and serve together. For these two reasons I believe we will eventually realize that we really are all Abraham’s children and that we really are all God’s children.

About the author(s)

Cardell K. Jacobson is Professor of Sociology at Brigham Young University. He earned a PhD at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill. He is the editor of All God’s Children: Racial and Ethnic Voices in the LDS Church (Springville, Utah: Bonneville Books, 2004).

Notes

1. Bruce R. McConkie, “All Are Alike unto God,” Book of Mormon symposium, August 1978, Provo, Utah, reprinted as “The New Revelation on Priesthood,” in Priesthood (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1981), 131–32. For a thorough treatment of the 1978 revelation, see Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 195–245.

2. Howard W. Hunter, “All Are Alike unto God,” Ensign 9 (June 1979): 72–74.

3. Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Need for Greater Kindness,” Ensign 36 (May 2006): 58–61; Gordon B. Hinckley, address given to regional conference of NAACP April 24, 1998, cited in Lois M. Collins, “Bridge Racial Barriers, Pres. Hinckley Says,” Deseret News, April 25, 1998, A1.

4. James A. Davis and Tom W. Smith, General Social Surveys, 1972–2000 (Chicago: National Opinion Research Corp., 2000).

5. Armand L. Mauss, “Mauss Surveys of Mormons, Salt Lake City and San Francisco, 1967–69,” electronic data files and documentation, American Religion Data Archives, University Park, Pennsylvania State University.

- Media and Message

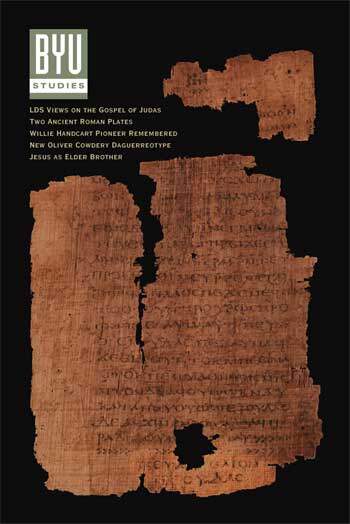

- The Manuscript of the Gospel of Judas

- The “Unhistorical” Gospel of Judas

- The Gnostic Context of the Gospel of Judas

- Judas in the New Testament, the Restoration, and the Gospel of Judas

- The Apocryphal Judas Revisited

- Two Ancient Roman Plates

- A Metallurgical Provenance Study of the Marcus Herennius Military Diploma

- Francis Webster: The Unique Story of One Handcart Pioneer’s Faith and Sacrifice

- Jesus Christ as Elder Brother

- The Salt Lake City 14th Ward Album Quilt, 1857: Stories of the Relief Society and Their Quilt

Articles

- “Will the Murderers Be Hung?”: Albert Brown’s 1844 Letter and the Martyrdom of Joseph Smith

- An Original Daguerreotype of Oliver Cowdery Identified

- This Is My Testimony, Spoken by Myself into a Talking Machine: Wilford Woodruff’s 1897 Statement in Stereo

Documents

- Judas: Images of the Lost Disciple

- All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage

- Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers

- Temple Theology: An Introduction

- The Mormon Vanguard Brigade of 1847: Norton Jacob’s Record

- Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel

Reviews

- The Oatman Massacre: A Tale of Desert Captivity and Survival

- Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts

- The Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Edition

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone