From Persecutor to Apostle

A Biography of Paul

Review

Thomas A. Wayment. From Persecutor to Apostle: A Biography of Paul.

Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006.

As author Thomas Wayment noted in a radio interview publicizing From Persecutor to Apostle, we know more about Paul’s life than we do about any other single person in the first century, and yet most of the books on Paul focus primarily on his teachings. In contrast, Wayment wanted to write a book about Paul himself, his family background, his early experiences, his missionary challenges, and his character in a way that would engage the general Latter-day Saint reader.

As an associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University with a PhD in New Testament studies from Claremont Graduate University, Wayment is well prepared to undertake such a study. He is coeditor of the excellent three-volume series of essays The Life and Teachings of Jesus Christ (2003, 2005, 2006) as well as coauthor of the beautifully illustrated and well-researched Jesus Christ and the World of the New Testament (2006), a reference book that is difficult to lay down once you pick it up. (I admit I bought at least ten copies for family and friends at Christmas.) Both previous projects draw on a wealth of current scholarship as well as insights from Latter-day Saint sources in a combination that offers readers the best of both worlds. In From Persecutor to Apostle, however, Wayment limits his citations, quoting only LDS General Authorities and ancient authors.

Wayment’s ancient sources are well chosen and woven into the text to enhance the narrative. Wayment quotes Epictetus on the terror of sea travel, Plutarch on the boldness of pirates, and Lucian on the rigors of imprisonment. He cites Epiphanus to explore a clue regarding his speculation that Paul, as a young man in Jerusalem, was rebuffed in his aspiration to marry the daughter of a priest. Nevertheless, in failing to introduce LDS readers to contemporary scholarship on the life of Paul, Wayment loses an opportunity to involve his Latter-day Saint audience in the process of evaluating historical evidence for themselves.

Most likely, Wayment wanted to focus on the flow of Paul’s story, not distracting readers with side issues and scholarly minutiae. However, this approach can be misleading. For example, Wayment asserts that Paul’s progressively failing eyesight was the mysterious “thorn in the flesh” Paul bemoans in 2 Corinthians, without considering any of the other interpretations scholars continue to ponder. Wayment’s arguments on this subject are intriguing (including Paul’s reference to large handwriting in a postscript he penned himself) but certainly not conclusive. Wayment fails to even entertain the possibility that the “thorn” was metaphorical and not physical. New Testament scholarship often depends on making the most of scarce information, using cultural and historical clues to illuminate brief scriptural references or resolve contradictions in scriptural accounts. Wayment underestimates his LDS readers by not providing footnotes, or even endnotes, so they can ponder alternative explanations or engage in further reading.

The strongest and most interesting section in From Persecutor to Apostle explores Paul’s early life and the historical circumstances that offered him such apt preparation for his role as the premiere emissary of Christ to the Gentiles. Wayment does an excellent job explaining how it was that Paul was born in Tarsus in Cilicia and why he was a Roman citizen. Although the fourth-century biblical translator Jerome claimed Paul was born in the town of Giscalis (in Galilee), meaning his parents were carried away by Roman soldiers during the unrest following the death of Herod the Great, Wayment suggests that the time frame works better if it was Paul’s grandparents who were taken to Tarsus as slaves. Such a scenario explains how Paul’s family could have had time to learn a trade, purchase their freedom, and accumulate enough wealth for their brilliant young son to attend the schools of rhetoric for which Tarsus was famous. At the age of nineteen or twenty, Paul journeyed to Jerusalem to study under Gamaliel, leader of the House of Hillel, the more compassionate of the two major Pharisaic schools. Wayment expertly evokes the first-century Jewish intellectual environment and carefully explores Paul’s motivation for persecuting followers of Jesus at a time when most other Jews tolerated them as just another variation on Judaism.

Throughout the book, Wayment demonstrates Paul’s prescient understanding of the challenge that Jesus the Messiah presented to the law of Moses. Wayment gives an intriguing explanation for the reason Paul went first to “Arabia” after his vision of the resurrected Lord. This area (actually the area of modern Jordan) was the land of the Nabataeans. According to tradition, they were descendants of Abraham through Ishmael’s oldest son and practiced circumcision. Thus, Wayment argues, Paul knew that he could preach the gospel freely among them without raising the undecided issue of circumcising Gentile converts to the gospel of Christ.

Wayment also offers the unsettled question of circumcision as one explanation for the difficulties Paul encountered in establishing churches on his first extended mission with Barnabas through Asia Minor. Wayment points out that Luke’s account in the Acts of the Apostles does not mention any baptisms between 30 and 49 AD. After 49 AD, however, when the council at Jerusalem definitively decided that circumcision would not be required for Gentile converts, Luke records many Gentile baptisms, beginning with Lydia’s household in Philippi.

In discussing the dynamics of the council at Jerusalem, Wayment provides some interesting insights into early church leadership, including the emerging role of James, the brother of Jesus, as the local leader of the church in Jerusalem and an advocate of maintaining Jewish traditions. James eventually weighs in on the side of Peter and Paul, requiring only that converted Gentiles abstain from meat sacrificed to idols, but James does not necessarily extend his approval to the table fellowship of Jewish and Gentile followers of Christ.

While visiting Antioch, an important missionary hub established by Paul, Peter is persuaded to stop eating with Gentiles under pressure from delegates from Jerusalem, and Paul is furious. Wayment characterizes Paul’s undiplomatic criticism of Peter as simply pride and insubordination, although Paul rightly anticipates the difficulties the Judaizers will cause as they follow his missionary trail from city to city, preaching the law of Moses and trying to turn his converts against him. (Were they the persistent “thorn in his flesh”?)

In evaluating Paul’s relationship to other early church leaders, Wayment tackles interesting questions about what qualifies someone to be called an Apostle and how Paul fit the criteria. In deciding who should replace Judas, the eleven remaining Apostles determined that the new Apostle should be a witness to the Resurrection from among those who had known Christ throughout his ministry. Limiting apostleship to men who matched these qualifications, however, would mean that the calling of Apostle could not continue into the second century. Wayment evaluates other criteria that are not so restrictive. Even though there is no evidence that Paul met Jesus during his earthly ministry, Luke implies that Paul should be called an Apostle by virtue of his witness of the resurrected Lord, and Paul himself claims the title on the same grounds (Galatians 1:1). Wayment also explores the possibility that Paul may have been ordained to apostolic office when he returned to Jerusalem after his second missionary tour.

In the book’s introduction, Wayment observes that after years of research, he finally gained an understanding of Paul as a person while traveling through many of the cities where Paul preached. As Wayment retraced Paul’s steps, “his experiences, struggles, triumphs, passions, and character fell into place for me. He became real, tangible, almost a present reality,” and Wayment explains that his motivation for writing his book on Paul was to help “others to experience what I have experienced” (xii–xiii). How well does Wayment succeed in giving his readers this sense of place, so key to the understanding of who Paul really was?

One of most difficult things in understanding Paul’s ministry is the profusion of unusual place names and unfamiliar geography related to his missionary experiences. Wayment tries to differentiate among them primarily by providing geographical detail and historical background. In Paul: His Story, a comparable biography published in 2004 by Oxford University Press, Jerome Murphy-O’Connor goes beyond physical description and historical setting to provide a great deal of ethnic and cultural detail. We feel that we know the Celtic Galatians well: tall and blond, with mustaches that become entangled in their food, hospitable but quick to fight, with exposure neither to Greek culture nor Jewish population. Murphy-O’Connor also makes the progress of Paul’s journeys more understandable by paying close attention to his missionary strategies. He describes, for example, the importance of establishing hub cities (Ephesus was such a missionary hub with key Christian communities within 200 to 300 miles in a 360-degree radius) and the advantages of earning one’s living along the way as a tentmaker (Paul could carry his tools in his pocketbook and had a skill needed in every city.)

On a more basic level, the wealth of interesting written material in From Persecutor to Apostle would be greatly enriched by a more interesting layout. The book provides only four maps, hidden on the end pages behind the flaps of the dust jacket. Any book on Paul’s travels should include many maps, illustrating the sweep of each mission as well as the environs of each major city. Ideally these maps should be placed near the text where each location is discussed, for quick reference. Furthermore, while color pictures are expensive, a few of them would be well worth the cost in a book relying so heavily on the readers’ appreciation of unfamiliar sites. Despite the lack of color photographs and the limited number of maps, I would encourage LDS readers to pick up From Persecutor to Apostle. If they do, they will be rewarded with many valuable insights into the life of the man who risked hunger and weariness, beatings and imprisonment, perils on the sea and perils in the wilderness to introduce the world to the gospel of Jesus Christ.

About the author(s)

Kathryn H. Shirts holds a Master of Theological Studies degree from Harvard Divinity School. She is the coauthor of A Trial Furnace: Southern Utah’s Iron Mission, published by Brigham Young University Press (Provo, Utah) in 2001.

Notes

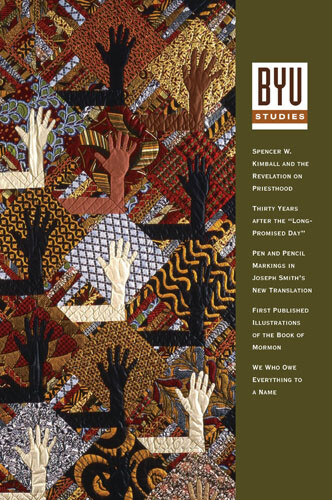

- Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood

- The Nature of the Pen and Pencil Markings in the New Testament of Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible

- A Picturesque and Dramatic History: George Reynolds’s Story of the Book of Mormon

Articles

- Tunica Doloris

- Fifth-Floor Walkup

Poetry

- The Great Transformation: The Beginning of Our Religious Traditions

- Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism

- From Persecutor to Apostle: A Biography of Paul

- Wounds Not Healed by Time

- History May Be Searched in Vain: A Military History of the Mormon Battalion

- The Civil War as a Theological Crisis

- Before the Manifesto: The Life Writings of Mary Lois Walker Morris

- The J. Golden Kimball Stories

- Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood

- Big Love, seasons 1 and 2

- The Dance

- Minerva Teichert: Pageants in Paint

Reviews

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

Tree of Souls

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X