Four LDS Perspectives on Images of Christ

Introduction

Introduction

-

By

Doris R. Dant,

As members of a Christ-centered church and consumers of a proliferation of visual images, Latter-day Saints face the enigma of wanting to know their Savior but not having a detailed description of either his mortal or resurrected physical appearance. How should an artist depict Christ? Why do individual members have both strong attachments and aversions to certain images? What conscious principles, if any, stand behind the selection of images for use in official and unofficial LDS publications?

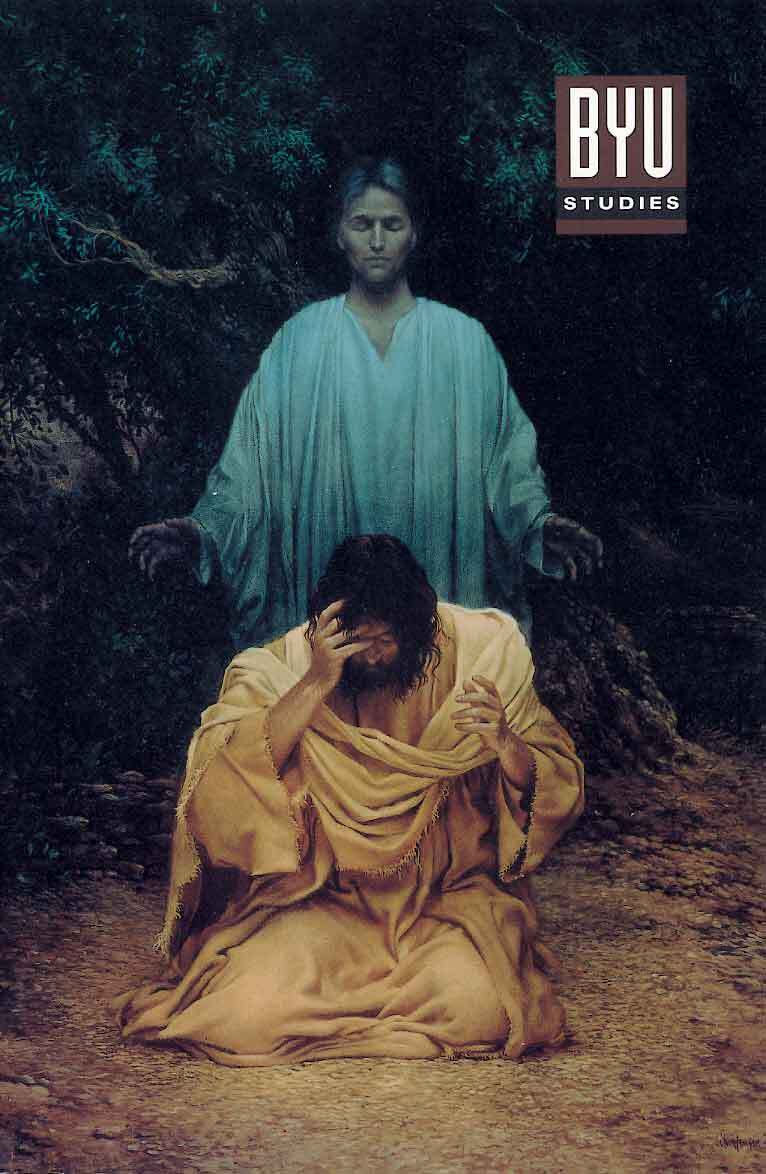

The following four articles in this issue of BYU Studies address these core issues from the perspectives of a Latter-day Saint artist, a cultural historian, an art historian, and a religion professor. Opening the discussion is James C. Christensen. Although best known as a painter of fantasy, Christensen has grappled for years with issues that unavoidably arise in painting the Savior. We asked him to share with us his personal resolution and while doing so to discuss his painting Gethsemane, which is featured on our cover. The result is an intimate—and profound—article, a testimony of the value of “taking up the gauntlet.”

A century of images forms the backdrop for Noel Carmack’s ambitious article on the role of images of Christ in Latter-day Saint culture. A preservation librarian and art teacher, Carmack argues that broad cultural forces in American religions as well as Church educational agendas underlie the popularity of certain images. These images, he believes, reflect changes over time in the LDS culture’s emphasis on certain characteristics of Christ.

The curator of the current exhibit of images of Christ at the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City and an art consultant for BYU Studies, Richard G. Oman has spent his career studying and exhibiting Latter-day Saint art. In his article, Oman takes as a starting point some modifications to Carmack’s generalizations. Then he uses these preliminary observations to remind us that great religious art invites us to answer the question, “What think ye of Christ?” Oman warns artists that if they “focus only on bright, cheerful, well-lit, tightly detailed images of Christ” they will miss the power of shadows. They may even unwittingly trivialize the depth of the Savior’s mortal experiences and of our potential response to our Lord.

A faculty member of Brigham Young University and photography editor for BYU Studies, Richard Neitzel Holzapfel issues a call to think more critically about our response to images of Christ. Not only should we learn about the differences between modern cultures and that of Israel two thousand years ago, but we should bring that sophistication to the scriptures and the images attempting to portray them. “[Our] preconceived ideas are often found hollow and wanting,” he writes. “Let Jesus be Jesus.”

Throughout these articles are interwoven several items of debate. As one example, Carmack predicts a single “ultimate Mormon visual likeness of Christ.” Moving us to that end, he claims, is Church correlation, which has “homogenized” the images sanctioned for appearance in official Church publications. Oman, on the other hand, notes the degree of “visual pluralism” enjoyed within the Church and sees it as one reason the Church has been so successful internationally. Christensen makes a case that in the premillennial world there will never be an ultimate likeness of Jesus. Each of us invents an image of Christ, and because these images differ, no one image will please everyone. To this process of invention, Holzapfel says, each individual brings “a personal religious, educational, and cultural background” that determines what is acceptable in an image of Christ.

In spite of the comprehensiveness of this discussion, some related issues remain to be addressed in future research. For instance, to what extent do the peace and prosperity enjoyed by many Church members in North America affect their preferences for certain artistic styles in paintings of Christ and the portrayal of particular character traits or events in the ministry of the Savior?

Since 1990, images of Christ have been featured on ten covers of BYU Studies, and representations symbolically referring to the Savior and the fruits of his Atonement have appeared on four additional covers.1 We offer this roundtable in the context of this emphasis.

About the author(s)

Doris R. Dant is Executive Editor of BYU Studies and Associate Teaching Professor of English at Brigham Young University. She has written on art for BYU Studies and with John W. Welch coauthored The Book of Mormon Paintings of Minerva Teichert (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 1997).

Notes

1. BYU Studies has published images of Christ on the following covers (listed as volume number, issue number, and year of publication): 30.3, 1990 (back cover); 33.3, 1993; 35.4, 1996 (both front and back covers); 36.2, 1996–97; 37.2, 1997–98; 37.4, 1997–98; 38.1, 1999; 38.4, 1999; and 39.3, 2000. The symbolic covers are found on 32.4, 1992 (tree of life, both front and back covers); 34.1, 1994 (the father of the prodigal son); and 38.2, 1999 (the Good Samaritan).

- That’s Not My Jesus: An Artist’s Personal Perspective on Images of Christ

- Images of Christ in Latter-day Saint Visual Culture, 1900–1999

- “What Think Ye of Christ?”: An Art Historian’s Perspective

- “That’s How I Imagine He Looks”: The Perspective of a Professor of Religion

- Examining Six Key Concepts in Joseph Smith’s Understanding of Genesis 1:1

- The Campaign and the Kingdom: The Activities of the Electioneers in Joseph Smith’s Presidential Campaign

Articles

- Mormon’s Map

- Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847–1896

- Sagwitch: Shoshone Chieftain, Mormon Elder, 1822–1887

- George Q. Cannon: A Biography

- The Church of the Ancient Councils: The Disciplinary Work of the First Four Ecumenical Councils

- The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries

Reviews

- The Dead Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints

- A Call to Russia: Glimpses of Missionary Life

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone