One Good Man

Review

-

By

Jim Dalrymple,

Christian Vuissa, director. One Good Man.

Provo, Utah: Mirror Films, 2009.

I had high hopes but reserved expectations while driving to see Christian Vuissa’s latest film, One Good Man. Though LDS cinema seems to have cooled and matured somewhat in recent years, it is nonetheless a movement that has generally been hit-and-miss at best. One Good Man comes as a welcome transition to deeper, more complex filmmaking. The film is far from perfect—it includes its fair share of cultural clichés and clunky sentimentality—but it also marks an insightful and timely turn toward a more intimate, nuanced exploration of LDS themes and culture.

One Good Man portrays a few days in the life of Aaron Young, an LDS father of six whose life appears to be reaching critical mass. As the film opens, Aaron has one son serving an LDS mission, a daughter preparing to get married, and a rebellious teenager. Compounding his stressful home life, Aaron’s boss demands that he lay off one-fifth of the company’s workforce to deal with the hard economic times. Just when Aaron thinks he cannot get any busier, he is called to be the bishop of his ward.

While the opening scenes expose one conflict after another, the remainder of the film stands back and allows these challenges to play out at their own pace. The result is illuminative. When Aaron comforts an elderly ward member, for example, or assuages the fears of his daughter’s non-Mormon in-laws, he is forced to adapt to a difficult situation. The decisions he makes are rendered as profound cinematic explorations of both the rewards and the challenges of being a Latter-day Saint. While some conflicts get resolved on-screen, others do not: Aaron works as a member missionary but without substantial results to speak of; he succeeds at work but is still dissatisfied with his job; his daughter gets married in the temple but never fully makes peace with her in-laws. By film’s end, the most substantial resolution is simply Aaron’s added maturity for having had certain experiences. In this sense the film is more a “slice of life” story than one that follows typical story form; although there is a beginning and an end to what the audience sees, there is no message about problems in life being solved quickly or easily.

To Vuissa’s credit, he knows who the film’s stars are and gives them time to shine. Clearly the strongest asset of the film is Tim Threlfall’s portrayal of Aaron. As the thoughtful but unassuming protagonist, Threlfall’s performance reaches into a complex realm that few, if any, other LDS films have dared to tread. His character often appears to be simultaneously rejoicing and grieving, offering thanks and questioning why. The most salient acting moments come when one tragedy or another strikes. In these moments, the camera lingers long enough for Threlfall’s performance to become a viscerally affective powerhouse of a man who is crushed. Though in these scenes he is usually alone and there is little dialog, Threlfall manages to portray a genuine grappling of the soul.

Adam Johnson portrays James Wellington, Aaron’s non-LDS friend and coworker. Johnson provides comic relief that manages to be appealing while not stereotypical. Johnson’s success seems to stem from an understanding of his character’s internal conflicts: while James is happy and carefree, he is also anchorless and lonely. The result is a complex character who is both inviting and sympathetic. Where Threlfall’s character deals with his challenges through varied emotional progressions, Johnson uses humor, providing some of the film’s most entertaining moments.

Complementing the strong performances, One Good Man demonstrates some remarkable cinematography. Vuissa wanted to establish Salt Lake City itself as a character, and cinematographer Brandon Christensen’s long, architecturally oriented shots succeed in tying the narrative to a unique physical space. Of course, Vuissa is no stranger to visually impressive cinema; the strongest aspect of his previous film, Errand oemgels, may well have been its portrayal of lush, Austrian locales. One Good Man is set in an environment that will undoubtedly seem less exotic to his audience, which in turn seems to have prompted greater creativity. While there are no thousand-year-old buildings to fill the frame, shots are composed in such a way as to visually challenge viewers to read new meanings into familiar settings. This rendering of Salt Lake City is even more remarkable considering the film was shot with a minimal budget of $200,000.

Though One Good Man represents a significant evolution for both LDS cinema and Vuissa, it is not, of course, perfect. Specifically, the music frequently dips toward the melodramatic, sometimes making the film feel didactic and preachy. If the actors’ performances are sensitive and explore the complicated nuances of life, then the music hits the audience over the head, telling them explicitly which emotion is appropriate for the scene. When Threlfall masters the simultaneous expression of exuberance and melancholy in a scene, the music cuts against his performance, reducing its poignancy.

The inadequacies in the music are compounded by the lack of story continuity. As both writer and director, Vuissa seems to have a knack for tapping raw human conflicts in everyday life; what links these conflicts, however, is more hit-and-miss. Many of the expository scenes unfold less gracefully than the more climactic moments. Thus, while there is rarely a moment that is not at least sweet and sincere, the emotional depth that the film achieves as a whole is less even.

Though One Good Man is not perfect, it offers a remarkably nuanced interpretation of its subject matter that I thoroughly enjoyed watching. Vuissa has said that he set out to make a film about a bishop, or a “judge in Israel,” but ended up making a film about a father who also happens to be a bishop. The comment is apropos given that Vuissa’s small body of work thus far is about individuals juggling various identities. In this way, One Good Man is less about teaching people about Mormonism (or making them laugh at its idiosyncrasies) and more about sharing what it means to be human.

About the author(s)

Jim Dalrymple recently completed an MA in English at Brigham Young University where he studied literary and cinematic depictions of the American West. He has also worked as a filmmaker and journalist and will begin his doctoral project in 2010.

Notes

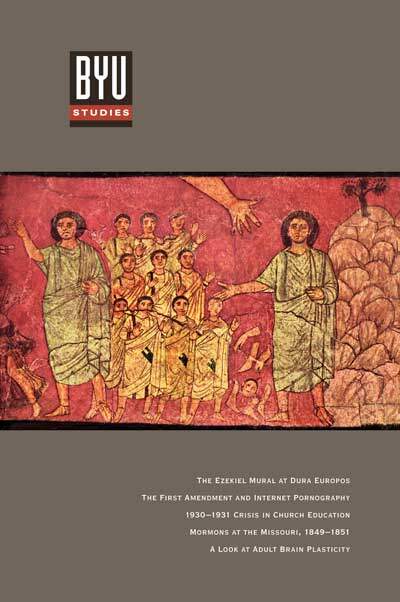

- The Ezekiel Mural at Dura Europos: A Witness of Ancient Jewish Mysteries?

- The Misunderstood First Amendment and Our Lives Online

- Joseph F. Merrill and the 1930–1931 LDS Church Education Crisis

- The Frontier Guardian: Exploring the Latter-day Saint Experience at the Missouri, 1849–1851

Articles

- Sorting, In Evening Light

Poetry

- Twisted Thoughts and Elastic Molecules: Recent Developments in Neuroplasticity

- Religion, Politics, and Sugar: The Mormon Church, the Federal Government, and the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company, 1907–1921

- The Tree House

- The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary

- One Good Man

- It Starts with a Song: Celebrating Twenty-Five Years of Songwriting at BYU

Reviews

- A Different God?: Mitt Romney, the Religious Right, and the Mormon Question

- Proclamation to the People: Nineteenth-Century Mormonism and the Pacific Basin Frontier

- In God’s Image and Likeness: Ancient and Modern Perspectives on the Book of Moses

- Understanding Same-Sex Attraction: Where to Turn and How to Help

- What’s the Harm?: Does Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage Really Harm Individuals, Families, or Society?

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone