Sail and Rail Pioneers before 1869

Article

Contents

Some cultural myopia in Zion blurs our views regarding our sail/rail/trail pioneer ancestry—those who immigrated to Utah with the aid of boats and trains as well as wagons and handcarts. We seem to presume that only covered-wagon experiences count or make one a “real” pioneer and that travel to wagon trail heads is unimportant or uninteresting. The condescension toward Saints who traveled by rail, especially after the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, can be seen in the pejorative term “Pullman Pioneer,” which was coined to distinguish those who came primarily by railroad from “real” pioneers who came by wagon. Yet most pioneers traveled by boat or rail from their ships or other starting points in the East to places in the West where the wagon trails began. Those important legs of their journeys were sometimes well over a thousand miles long—a real story, a real journey, which was in many cases as hazardous and arduous as the final trek across the plains.

Of the approximately 70,000 LDS pioneers who between 1831 and 1869 immigrated to their various Zions in Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, and Utah, more than 90 percent traveled part of the way by water—a fact little noted nor long remembered in Mormon historiography.1 They traveled on the Saint Lawrence, Pecatonica, Ohio, Mississippi, Missouri, Genesee, Hudson, Rock, and Illinois Rivers; on the Montezuma, Erie, Pennsylvania State, Ohio and Erie, and Miami and Erie Canals; and on two of the Great Lakes—Lake Ontario and Lake Erie—as well as on Cayuga Lake.

They utilized the many forms of water transportation of their day, including sailing sloops and schooners; steamboats of all sorts, especially side and stern paddle riverboats; and various canalboats—the slow line boats and the faster packets. Many steamships and sailing ships operated on the Great Lakes. Steamboats were preferred for maneuverability but were not well suited to carrying large cargoes, so two-masted schooners were also used.

In addition, a surprisingly large number of immigrants were rail/trail pioneers.2 Between 1840, when Mormon converts from Europe began sailing to the United States of America, and February 1855, 93 percent of those immigrant companies entered the United States at New Orleans, where they obtained passage on riverboats to their jumping-off places for their journeys west.3 After 1855, however, as railroad lines pushed farther west, Latter-day Saint immigration patterns changed; all European immigrants then entered the United States at Philadelphia, New York City, or Boston and took various railroads as far as possible to river ports or trail heads in the Midwest. Of the total of 148 Latter-day Saint companies sailing to the United States between 1840 and the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, 73 took railroads all or part of the way from the Atlantic Coast to the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. In other words, of the approximately seventy thousand LDS wagon pioneers who crossed the plains, some thirty-four thousand (49 percent) traveled by railroad for at least one stage in their journey to their waiting wagons and handcarts.

Thus, travel by boat and train forms a larger piece of the westward Mormon migration than previous studies of the Mormon Trail have noted.4 This article strives to correct that deficiency.5

The problem has not arisen because no rail and water accounts occur in the diaries or letters of pioneers; the problem is that we as a people think in terms only of wagon or “real” pioneers, not of water or rail pioneers. (I also get the feeling that the immigrants themselves did not feel much like real pioneers either until they got to their wagons.) Hence historians and catalogers pick up only wagon reports—no one “trailed clouds of glory” while on a train or boat! Yet, while rail and water travel was usually of shorter duration and not particularly conducive to long journal entries, it was an important part of the total picture. We are very lucky to know what we do about it.

Sail/Trail Pioneers

Water Routes. During the 1830s, Mormons were bent on reaching Kirtland, Ohio, and various places in Missouri. En route to Kirtland, they traveled from various starting points via Lake Cayuga, the Montezuma and Erie Canals, and Lake Erie. To Missouri, the preferred route was via the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri Rivers.

From 1840 through 1845, most Mormons traveled to Nauvoo from the East Coast or from New Orleans. From the East Coast, they mainly utilized the Erie Canal; Lakes Ontario and Erie; and the Hudson, Saint Lawrence, Ohio, and Pecatonica Rivers. From New Orleans, they took the Mississippi River. As the Mormons left Nauvoo in 1846, many traveled the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers to the Council Bluffs, Iowa, area.

Throughout the 1850s, most Mormon pioneers traveled the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers (mainly from New Orleans) to various jumping-off places at Saint Louis, Westport, Jefferson City, Alexandria, and Churchill, all in Missouri; Keokuk and Council Bluffs in Iowa; Fort Leavenworth and Atchison in Kansas Territory; and Florence and Omaha in Nebraska Territory.6

During the 1860s, most Mormons were able to ride various railroads from the East Coast to Saint Joseph, Missouri, where they took riverboats on the Missouri upstream to Council Bluffs or Omaha. In 1867 Mormon western travel by boat almost completely ended when the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad reached Council Bluffs and linked up with the Union Pacific. Two years later, Mormon immigrants could travel all the way from the East Coast to Utah by rail.

Experiences of Water Pioneers. As would be expected, with more than sixty thousand Mormons traveling for many years on all kinds of lake, river, and canal craft, they experienced about all the good and the bad that normally went with water travel during the nineteenth century. For the most part, Mormon experiences on the water were typical of their time and place. Bad weather, wind, rain, ice, miserable accommodations in deck and steerage passage, heat, insects, accidents, incidents of falling overboard, insults, disturbances caused by the Civil War and “Utah War,” episodes of being left on shore, seasickness, cholera, threats from a “wicked” crew, discomforts over slavery, boiler explosions, occasions of running aground, miscarriages, stillbirths, deaths, quarantine islands, snags, sandbars, broken rudders, breaks in canals, slowness, lack of shelter and proper sanitation, poor food, stench, and crowded conditions characterized river travel in that day.

Not all aspects of travel by water were negative, however. Journal entries describe natural beauty, church services, preaching invitations, games, cabin-class accommodations, organized activities, boat races, practicing phrenologists, kind crew members, and friendly officers, maids, and waiters, to name only a few of the more enjoyable aspects of these trips.

The first Mormon grumping took place in 1831 on the Erie Canal en route from New York to Kirtland. Joseph Smith’s mother, Lucy, ran a tight ship (quite literally) and expected the immigrating company she was leading to conduct themselves in a saintly manner. She chastised mothers for being careless with their children, anyone else for complaining about having left good homes, and the sisters for sitting around pouting and for flirting with gentleman passengers who were strangers and not members of the Church.7 The account of this boat’s daring departure from the Buffalo harbor into an ice-filled Lake Erie is one of the most thrilling adventures of early Mormon travel. Turning to the motley and harried band of converts on her boat, Lucy called out:

“Now Bretheren and sisters, if you will all of you raise your desires to heaven, that the ice may be broken up, and we be set at liberty, as sure as the Lord lives, it will be done.” At that instant a noise was heard, like bursting thunder. The captain cried, “Every man to his post.” The ice parted, leaving barely a passage for the boat, and so narrow that as the boat passed through the buckets of the waterwheel were torn off with a crash, which, joined to the words of command from the captain, the hoarse answering of the sailors, the noise of the ice, and the cries and confusion of the spectators, presented a scene truly terrible. We had barely passed through the avenue when the ice closed together again, and the Colesville bretheren were left in Buffalo, unable to follow us.

As we were leaving the harbor, one of the bystanders exclaimed, “There goes the ‘Mormon’ company! That boat is sunk in the water nine inches deeper than ever it was before, and, mark it, she will sink—there is nothing surer.” In fact, they were so sure of it that they went straight to the office and had it published that we were sunk, so that when we arrived at Fairport we read in the papers the news of our own death.8

Weather was a frequent problem. Bad weather and ice held up canalboats and sailing vessels on the Great Lakes. Records talk of the heat on the lower Mississippi and of rain on open and unprotected decks.

There was seasickness, of course, and much worse—deaths from cholera (a waterborne disease), especially during the bad years of 1849 and 1850, when some were quarantined near Saint Louis.9 Corpses, if not thrown overboard, were buried in the riverbank. (Riverboats often carried coffins for just such use.) Once, in 1849, when some Saints requested a captain to stop for a proper burial, he stranded them. According to the account, “The captain was a brutal, unaccommodating, and a very, extremely harsh man.” He weighted corpses and dumped them overboard. One Latter-day Saint died, and a brother, George Wood, got permission to make the burial onshore and “hired a Negro to help dig a trench.” Before the burial was completed, the captain sailed off, leaving the burial party on the shore. The general appeals of the passengers were of no avail. Then a Mormon, Joseph Walker, found some rope and threatened to hang the captain: “We’ve tried persuasion to see if there is any humanity in your worthless carcass. See this rope. If you don’t go back to those people, I’ll hang you from your own cross beam and I’ll have plenty of help to do so.” The captain returned.10

Deaths occurred from falling overboard. Children, especially inquisitive boys, were the most vulnerable. The sources record some routine, but nonetheless tragic, losses of life.11 In 1851 between New Orleans and Saint Louis, an English convert known as Sister Shelly attempted to draw a bucket of water from the river while the boat was running, and the force of the current drew her in. The records note that “she floated for a moment and then sank to rise no more. The engines stopped immediately and a boat manned and sent in search of her, but it was unsuccessful in obtaining the body.”12 Sadly, this is just one more example of how totally ill-suited the female attire of that day was for westering—her water-soaked, heavy skirts obviously drew her under.

In 1863 a crew member opened a trapdoor in the bottom of the riverboat to get water and forgot to close it. Notes one of the immigrants, “A small boy became frightened when some mules in a stall nearby started kicking and made a lot of noise. He became excited and fell through the trapdoor. They stopped the boat and searched, but found no trace of his body. They thought he might have been struck by one of the large wheels on either side of the boat.”13

That same year, a group of Latter-day Saints were on a flatboat with no railings traveling from Saint Joseph, Missouri, to Florence, Nebraska. During the night, the boat laid to for wood. A boy of about twelve, apparently half asleep, walked off the boat into the river. The swift current swept him away in an instant, and he was lost.14

In 1842 a poignant notice appeared in the Times and Seasons, a Mormon newspaper published in Nauvoo, concerning a lost child:

INFORMATION WANTED

As the Steam Boat General Pratt, was on her way from New Orleans to St. Louis, on the 15th of Nov. last, while about half way on her passage Mary, the eldest daughter of William and Mary Butterworth, of Macclesfield, Eng. 11 years of age, accidentally fell over board and although the captain of the boat instantly returned some distance and used every exertion to recover the body, nothing has yet been heard of it. If any one has found the body, and will give information thereof and the place of its deposit, they will greatly oblige, and soothe the feelings of the afflicted parents by giving notice to the Editor of the Times and Seasons. Editors on the Mississippi will please copy.15

Perhaps the most unusual detail in a drowning account came from an 1851 accident on the Mississippi River. A man, apparently not a Mormon, fell overboard. “The boat was stopped instantly, and every effort was made to save him, but to no purpose. As he sank he threw his pocketbook, which was picked up by one of the men and given into the hands of the clerk, in order to be restored to the relatives of the deceased.”16

Accommodations and food were often bad. Most Mormon immigrants were poor, so they usually booked deck or steerage passage, suffering from bad stench, sleeping wherever they could, and eating as best they could. A few could afford cabin class, but they were exceptional. On rare occasions, Mormon agents would book an entire boat.17 Most immigrants brought food with them and prepared it as circumstances permitted. Sometimes their food was stolen by the crew. In other instances, Mormons earned food scraps by helping the deckhands; a riverboat could burn up to forty tons of wood a day, and help was always needed to “wood up” on shore.18

Nagging problems such as getting stuck on sandbars, running aground, catching snags, and breaking rudders or paddle wheels kept life interesting. Other, more serious, problems were steamboat disasters that claimed thousands of lives. Exploding boilers, when captains tried to make time, were a constant threat.19

Occasionally passengers wrote about unpleasantries with the crew and boat personnel. One case is notable. In 1851 an English immigrant, Frederick Weight, on the trip from New Orleans to Saint Louis, claimed, “The crew was made up of very wicked, cursing men, who cared nothing for anything good.” This good man’s opinion was probably colored by the fact that the head cook fell in love with Weight’s wife and threatened to shoot him!20

One experience often commented on negatively, especially by the European Saints transferring from ocean vessels to riverboats in New Orleans, was the evil of slavery. In 1854 in New Orleans, a Danish convert “saw black slaves at work, thirty to fifty in a gang. On the steam ship are six blacks. They do the heaviest work. They buy them here for $25.00 each.”21 James Moyle from England went to the slave market and saw the slaves that were being sold that day. It was “revolting to my feelings to see the men, women, and children that we saw there sold like cattle or horses, and although they had a black skin they were human beings.”22 A sister, Emma Higbee, related a relative’s experience: “She saw children taken from their parents and given to rough traders. The storms at sea did not seem nearly so terrible as that auction sale with human lives and happiness at stake.”23

In 1851 one of the superior Mormon diarists described her experience with slavery in New Orleans as follows:

The only thing which detracts from its beauty is the sight of hundreds of Negroes working in the sun. “Oh slavery, how I hate thee.” [She visited a female slave market. (“No lady enters that for males.”)] It is a large hall, well lighted, with seats all round on which were girls of every shade of color, from ten or twelve to thirty years of age, and to my utter astonishment they were singing as merrily as larks. I expressed my surprise to Mrs. Blims and she said “Though I, as an English woman, detest the very idea of slavery, yet I do believe that many of the slaves here have ten times the comfort of many of the labourers in our own country with not half the labor. I have been thirteen years in this country and although I have never owned a slave, or intend to do so, still I do not look upon slavery with the horror that I once did. There are hundreds of slaves here who would not accept their freedom if it was offered to them. For this reason they would then have no protection, as the laws afford little or none to people of color.”

I could not help thinking that my friend’s feelings had become somewhat blunted, if not hardened by long residence in slave states.24

On board other boats, there were births as well as miscarriages. At Saint Joseph, Missouri, four men had to carry a poor sister off the boat in her bed. There were stillborn children—twins, for example—in Keokuk.25

Some rather unusual trials were endured, especially by Mormons. In 1844, for example, the Maid of Iowa, a Mormon-owned riverboat carrying immigrants, passengers, and cargo to and from New Orleans, was attacked on its way to Nauvoo. According to William Adams, when word would spread that a Mormon boat full of Mormons was coming, they were insulted wherever they landed for supplies. At one place, the boat was actually set on fire and even fired upon. Adams also noted that one boat on the Mississippi south of Saint Louis tried to run the Maid of Iowa down and that Captain Dan Jones avoided a collision only by threatening to shoot the pilot of the other boat.26

Several accounts of boat travel in 1858 involve the “Utah War.” Over both land and water, Mormons were adversely affected by the unnecessary military expedition to quell a nonexistent rebellion. Elder John E. Hill, returning home from his mission to England, took a Missouri boat from Saint Louis to Omaha which also carried teamsters and supplies for the Utah War. James Bunting may have been on the same boat, for he described his as carrying “Uncle Sam’s wagons intended for the Utah Expedition.” He noted that at Fort Leavenworth his boat, the Saint Mary, received a salute from the Minihaha, on which were others bound for Utah. The army supplies were unloaded at Nebraska City and freighted west on the Nebraska City Cutoff Trail.27

The most dramatic “Utah War” experience was recorded by Martin Luther Ensign. He and other returning missionaries noted that “when they left the [Saint Louis] wharf they fired a cannon and hurrahed for Utah and the G. D. Mormons and said if they knew there was a Mormon on board they would through [sic] them in to the river, but we kept mum and they did not find out we were Mormons or give us any trouble.”28

The Saints, like many others, were also affected by the Civil War. Boat travel, like train travel, was sometimes interrupted, crowded, and even dangerous—especially in Missouri, which not only fought on the side of the Union during the war but also had its own private civil war. Quantrill’s Raiders, Bloody Bill Anderson, and other pro-Southern forces in Missouri not only tore up railroad tracks to harass the Union forces but occasionally fired on riverboats.

In 1862 some deckhands refused to work on a riverboat along a stretch of the river where they could hear gunfire, so the captain ordered the strikers off and replaced them with Mormons for one dollar a day plus board. The Mormons were, of course, disliked for being scab labor.29

In 1863 a party of Mormons left Saint Louis for Omaha and the West. On board were five hundred mules and horses, one cannon, and troops to protect these military supplies. The troops barricaded the boat as best they could by erecting breastworks of sacks of grain and tobacco.30 In 1864 some Confederates fired on a boat that carried Mormons, but no one was hurt.

On the positive side, Mormons commented on the natural beauty of the countryside, fields of corn, pumpkins, apple trees loaded with fruit along the Erie Canal, and the forests of tall and stately trees along the lower Mississippi River. In 1842, Richard Rushton noted “the rocks on the right side of the river . . . were enchantingly beautiful.” This is most likely a reference to the bluffs on the Illinois side of the river between mileposts 25 and 35 upriver from Saint Louis (between Alton and Grafton). Today they are still “enchantingly beautiful.”31 About ten years later, Jean Pearce, one of my favorite journalizers, commented on these same bluffs: “I cannot describe,” she said, “the grandeur of the scenery—it is most appalling!”32

One rather interesting and detailed 1854 account of a trip from New Orleans to Saint Louis starts out with a bit of rhymed doggerel:

WE WAS CROWDED

Now we are traveling up the river

Crowded in that little Steamer

But still we felt to ask the Lord

For to protect us all on board.The steam boat a puffing and snorting and pushing hard against the streem, but oh, what a durty watter for us to use. We dip it up for to settle it, but don’t get much better. Never mind, we will do the best we can with it. I must drink it, anyhow, because I am very thirsty.

And what a rackety noise, it made me shudder. The Captain a shouting and the watter a splashing and the band a playing and some of us singing and some of the sisters a washing and the babies a crying and the sailors a talking and many of them smoking. And all of us trying to do something and the boat a tuging and snorting when traveling up the Missouri river, also the Mississippi. Indeed it was a great sight to us to see such forests of timber and land.

What a wonderful stream this is going in such a force taking down some very large logs. They some times strike the boat with tremendous blows, but we got through all right. We got to St. Louis about the 10th of April 1854. And was glad to get there. But what a durty looking place this is to be sure.33

A few accounts mention church services on the riverboats—naturally enough, with Mormons being eternally alert for an opportunity to preach the gospel. For example, in 1856 returning missionary Samuel Woolley was invited to preach in the ladies’ cabin.34 Mormons, as would be expected, also sang and prayed together. Children played games. One mother in 1851 set her children “to work on perforated papers.”35 Other children played “drafts” (draughts or today’s checkers) and cards.

Some well-off immigrants had pleasant accommodations. In 1851 on the Mississippi River, Elizabeth Goddard noted, “The Captain and officers and chamber maid were all very kind . . . the colored waiters were quite delighted to wait on the children and also the chamber maid who was also colored.”36 In 1853 returning missionary Joseph W. Young reported that the “crew was very kind” and that his company of Saints were “comfortable.”37

Riverboat phrenologists gave readings. In 1856 Samuel Woolley recorded, “There is a phrenologist on board who wished to feel my head, so I let him do it. He gave me a very fair reading of my head.”38

Most Mormons probably enjoyed the occasional races between rival riverboats—unless, of course, the boilers blew up from too much pressure. In 1866 one immigrant described how the ship’s lifting machinery pushed the boat off a sandbar—a maneuver called “grasshoppering”—which certainly gave the passengers something interesting to observe.39

Rail/Trail Pioneers

By 1827, Americans had experimented with railroads, the new form of British and European transportation, and in May 1830 railroad travel effectively commenced in America with the opening of the first division of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Beginning in 1837 and during the next two decades, most Mormons traveled as far west as possible by rail toward Kirtland and Nauvoo, then by water or land to trail heads on the Missouri River usually, and ultimately to Utah.40 After 1855 railroads ran far enough west that Latter-day Saint immigrants were encouraged by Brigham Young to stop coming through New Orleans and to enter the United States on the Atlantic seaboard. This route offered a faster, cheaper, and safer way of bringing European converts to Utah—cholera, for example, was a constant threat of river travel.

Rail/trail pioneers spent relatively little time on the much faster trains, which could go night and day. In the 1850s, immigrant trains ran about 12 miles an hour, while an “express” averaged 27.5 miles an hour. An immigrant could cross Illinois in fifteen hours and Missouri in twelve. By 1867, when the Union Pacific Railroad reached North Platte, Nebraska, the average time from New York City to that railhead was six days.41 By 1869 an express took only eighteen hours from Chicago to Council Bluffs. Rail/trail travel, consequently, generated relatively fewer reports of “faith promoting” experiences. Train travel was hardly the great test of faith that wagon travel was; therefore fewer immigrants left behind accounts of adventurous rail travel.

Rail/River Routes 1855–1856. After the 1855 switch in ports of entry from New Orleans to the main eastern cities but before the 1856 completion of railways extending to Iowa City, eleven pioneer companies, totaling 4,121 immigrants, had landed at East Coast ports and had taken one of several rail and river routes to the trail head on the Missouri River at Atchison/Mormon Grove, Kansas Territory. Some companies took the Pennsylvania Railroad from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, where they switched to boats on the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri Rivers to complete the trip to their jumping-off place. A few took rail and sail via New York City; Dunkirk, New York; Cleveland; Chicago; and Saint Louis. Still others took a mixture of various railroads (especially the Michigan Central) and riverboats and lake boats to Chicago, from whence it was possible to take the Chicago and Alton Railroad to Saint Louis.42

From Saint Louis, many immigrants took riverboats on the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers to various trail heads, such as Westport and Independence, Missouri; Fort Leavenworth and Atchison/Mormon Grove, Kansas Territory; as well as Council Bluffs, Iowa.43 Others continued west from Saint Louis by train. In 1854, for example, some Saints took the Pacific Railroad some 122 miles from Saint Louis to Jefferson City, Missouri, the end of the line, then went by wagon to Independence where they picked up the Oregon Trail to go west.44

The Chicago and Rock Island Railroad: 1856–1859. Routinized Mormon immigrant rail travel properly commenced when the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad (C&RI) reached Iowa City in the spring of 1856.45 It was then possible to take various trains from Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia, via Chicago, all the way to Iowa City—a distance of some one thousand miles. The account of one Mormon company that came this way can be paraphrased as follows: we debarked at Staten Island; got certificates of good health; avoided baggage inspection; cleared immigration at Castle Gardens; a steamboat took us to Piermont, New York, where took railroad for Dunkirk, New York; took Lake Erie steamboat to Toledo (stopping at Cleveland and Sandusky); thence by rail to Chicago and on to Iowa City.46

Brigham Young (or at least he is given credit for it) initiated this change in the immigration pattern. In September 1855, he wrote the president of the European Mission, “I think the emigration had better come the northern route from New York, or Philadelphia, or Boston, direct to Iowa city” and then travel by handcarts.47 Brigham Young wrote this instruction seven months before the C&RI Railroad reached Iowa City on April 21, 1856. He was obviously well informed of the railroad’s construction plans and needed to alert England before the 1856 immigrant season commenced.

Almost immediately Mormon immigrants began to take the C&RI Railroad west from Chicago to Iowa City. The first to do so were the famous handcart pioneers, whose first immigrant company to go by ship and rail to Iowa was called the “Enoch Train.” It sailed from Liverpool on March 23, 1856, and arrived in Boston on April 30 and in Iowa City on May 12.48 Since this journey was the beginning of the famous handcart immigrant experience, there are many extant rail/trail accounts of this route for the years 1856–57, but all are, regrettably, bare boned.49

By 1860 the C&RI Railroad had pushed beyond Iowa City to Marengo, and a few Saints or small independent pioneer companies rode to that point and then took stagecoaches or wagons to Council Bluffs.50 The C&RI Railroad did not reach Council Bluffs until 1869, two years after the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad.

The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy and the Hannibal and Saint Joseph Railroads: 1859–1866. An even more important development in the Mormon rail/trail experience came in 1859, when the Hannibal and Saint Joseph (H&StJ) Railroad reached the Missouri River at Saint Joseph, Missouri (the first railroad to do so). Consequently, the Mormons quickly changed from the C&RI to the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy (CB&Q) Railroad because at Quincy immigrants could take a riverboat some sixteen miles downstream to Hannibal and entrain for Saint Joseph on the H&StJ line. The 288-mile-long CB&Q Railroad, made up of several “short lines,” had already reached Quincy in 1855. There was no reason, however, for the Mormons to use it until the completion of the H&StJ in 1859. Riding these two railroads in sequence made immigrating much easier and faster. Saint Joseph, then the westernmost point on the national railway system, was about 240 miles farther west than Iowa City.51

The best, but not very good or even typical, Mormon account of the fifteen-hour CB&Q train ride across Illinois is as follows: “Arrived at, Chicago a fine place, Left there about 12 [noon]. A fine view of the lake, a very many vessels in sight. . . . Illinois appears to be a flat fertile country. Hundreds of cattle grazing on the prairies. . . . Stopped at a village and cleaned them out of bread.”52

The following non-Mormon account from 1862 is more descriptive:

The jaunt across Illinois was attended with no particular circumstance worthy of note other than what ordinarily befalls railway travelers. The line of the road was through a beautiful prairie country, tho the sameness of it grew monotonous. The road bed was uniformly level and smooth, and riding not more than unusually [sic] tiresome. . . .

The company was congenial and time passed easily and when one tired of looking out over the vast expanse of prairie, and admiring the fine farm houses and sleek cattle everywhere, one could read a book.53

In 1860 a spur from West Quincy, Missouri, intersected the H&StJ at Palmyra, Missouri, making it possible for the Saints to avoid steamers to Hannibal by taking a ferry to West Quincy. In 1865 one non-LDS traveler described his experience on this ferry; his experience was probably similar to what the Mormons knew:

Our ferry-boat was but a placid-looking old scow, moored to posts on the beach, with a single deck, roofed to enclose a small, stuffy cabin, filled to its capacity with a rough-looking, rugged, scrawny crowd—apparently good-natured and quiet enough. . . . We stood so closely packed together that the captain elbowed his way through with difficulty to collect his “one dime” fare, which he did on the voyage over—a matter of twenty-minutes of yawing this way and that, broadside of a strong current.54

The 207-mile-long H&StJ railroad, built during the years 1856 to 1859, was the first railroad to cross Missouri and, more importantly, was also the first to reach the Missouri River.55 The first Mormons to ride the H&StJ formed the eighth handcart company at Florence in 1859, the only one to cross the plains that year.56 Unfortunately, I have found no good LDS account of traveling by rail across the state of Missouri.57 However, in 1859 another traveler recorded the following, which may have been representative:

Today . . . started for St. Joseph. Soil, all along first rate. Timber: oak, honeylocust, bass, cottonwood and buttonwood. Plums and crabapple bushes. Grape-vines climb to the tops of the highest trees. Vast prairies of good soil. But little wheat seems to be sown along this route . . . we only crept along; and such jolting . . . sometimes the locomotive seemed to wheeze as if a violent cold has seized it, then it would start ahead as if chased by the coyote wolves.58

Another disgruntled passenger dubbed it “The Horrible and Slow-Jogging Railroad.”59

From Saint Joseph, immigrants took riverboats up the Missouri River some 160 miles to the area around Council Bluffs and Florence (North Omaha), where they joined wagon trains west.

In 1859 and beyond, some Saints found it cheaper and more convenient to reach Saint Joseph via Canada. This somewhat unusual routing was by boat up the Hudson River from New York City to Albany and by rail to Niagara, New York; Windsor, Canada, via the southern tip of Ontario; and Chicago via Detroit.60

From 1864 to 1866, the preferred jumping-off place for westering Mormons shifted from Florence to the small river community of Wyoming in Nebraska Territory (near Nebraska City) forty-five miles south of Winter Quarters. This shift spared Mormon immigrants the unpleasantries of meeting the apostates and “go-backs” who were then tending to congregate in Council Bluffs. It also shortened the upriver journey to Winter Quarters by forty-five miles and the overland trek by about one day.61

A variant on the CB&Q and H&StJ route commenced in 1859, when the Missouri Northern Railroad from Saint Louis connected with the H&StJ at Macon, Missouri. From then on, Latter-day Saint immigrants could pick up the H&StJ via Saint Louis.62 LDS accounts of using this railroad are very scarce. The religious affiliation of one traveler, Joseph Tod Hunter, is unknown. However, he left behind a brief account of his trip going east from Saint Joseph to New York City in 1868 that seems typical of the experiences of many rail pioneers:

From St. Joseph by rail we went through fine undulating country, apparently very fertile and most settled. We were delayed for two or three hours in consequence of a train being off the track, not an unusual thing in these parts. After a night in the cars, we stopped for breakfast at Montgomery. . . . After passing through a large tract of oak forest we again came on the Missouri at St. Charles, where the cars were run bodily on to a huge ferry and carried across to the line on the other side, and we soon steamed in to the great city of St. Louis.63

The Chicago and Northwestern Railroad: 1867–1869. In 1867 another railroad west became available to the Saints. This was the Chicago and Northwestern, the first railroad west of Chicago, started in 1847, the year of the Saints’ great trek. This line, five hundred miles long, consisted of several short lines and reached the Mississippi River in 1855 and Council Bluffs on the Missouri in 1867. It was the first railroad to do so. Some Mormons started using this route early in 1868. Thereafter, because it became the preferred carrier between Chicago and Council Bluffs or Omaha, it also became one of the most important rail lines in Mormon immigrant history.64 It used the ferry to go from Council Bluffs to Omaha, where it linked up with the Union Pacific Railroad. Two years later, in 1869, immigrants could go by train from the Atlantic to Ogden, Utah.65

A short account by Zebulon Jacobs, a member of the first company of Mormons to ride the Chicago and Northwestern line to Council Bluffs, is interesting:

We are passing through Illinois, the state where our beloved prophet was murdered. Our coming has been heralded in advance with considerable excitement in consequence as we passed through. We are the first company of Mormons ever passing through the country on cars [he means the first company of Mormons on the C&NW]. There is considerable anxiety to see some live Mormons; some were very rough and insulting, some were more civil. Some tried to force their way into the cars to insult us.66

The Keokuk and Fort Des Moines Railroad. For a variety of reasons including the Civil War, some Mormons utilized the Keokuk and Fort Des Moines Railroad, beginning in 1857, when the line was still under construction. That year Samuel W. Richards made the journey in reverse, following the Mormon Trail east to Florence and then traveling by wagon and stage to Iowa City, by river and rail to Keokuk, and then by riverboat to Saint Louis. In 1861, William Hart Miles took the CB&Q west to Quincy, traveled by boat down the Mississippi River to Keokuk, Iowa, from where he rode the Keokuk and Fort Des Moines Railroad as far as it went, and thence traveled by stagecoach to Council Bluffs to pick up the Mormon Trail.

A few Saints took other variants of the above-mentioned routes. By 1868 the Council Bluffs and Saint Joseph Railroad enabled a few Mormons to avoid riverboats between Saint Joseph and the Omaha area.67

Experiences of Rail Pioneers. Mormons, because they almost always traveled in “emigrant cars”—that is, the cheap cars rather than the first-class and “palace” cars—experienced most of the discomforts typical of mid–nineteenth-century railroading. Among the standard problems were crowding (up to eighty-four in each car), uncomfortable cars, poor heating, bad ventilation, dim lighting, marginal sanitary facilities, few if any sleeping arrangements, inadequate eating conveniences, and a lack of drinking water; loud noise, strong smells, jolting, shaking, vibration and fatigue;68 an abundance of dirt, lice, soot, sparks, smoke, and fire; gamblers, thieves, tramps, drunks, marauding soldiers, impolite railroad personnel, and “mashers” who tried to “take advantage” of women; loss of luggage; plenty of snow and ice; and such other inconveniences as sickness, bad breaks, animals on the tracks, derailments, accidents, wrecks, delays, Civil War destruction, deaths, and births. Mormon immigrants understandably tended to highlight such trials and tribulations to accentuate their faithfulness and sacrifice for the gospel. Some specific instances follow.

In 1860 along the H&StJ, a “sister Keller gave birth to a child”; in 1862 on the CB&Q, a sister Spencer “was confined.” Children died on the CB&Q and the H&StJ; in 1864 thirty-three immigrants died at the end of the track in Saint Joseph, Missouri, and Joseph W. Young had the sad duty of burying them in the Saint Joseph cemetery. B. H. Roberts tells of a deranged woman, who in 1866 “ran wild in the cattle cars, screaming and clapping her hands; [she] had to be forcibly subdued, tried several times to destroy herself by leaping out of the train.”69

In 1864 the train in which Mary Ann Webb was riding jumped the track, but she was unhurt. Occasionally, sparks from the engines caused fires which sometimes destroyed baggage.70 Some immigrants complained of a “bitter spirit in Chicago” and of “cross conductors”; in 1862 one “conductor” (engineer) even opened the throttle to sixty miles an hour and said he would drive the “Mormons to hell.”71

Most immigrants sat up all night, since few could afford berths or even rented pillows; some, between connections, slept in barns and warehouses. Brigham Young Jr. was delayed by snow. Eating was catch-as-catch-can—grabbing anything handy at short meal stops and buying things from “butcher boys” (vendors on the trains) or from farmers and their wives at train stops.

While immigrant cars were primitive, they were much preferred to the lice-ridden cattle cars that some pioneers traveled in. However, not all of this travel was unpleasant. F. W. Blake wrote: “The conductors are very gentlemanly in their behavior. I have had conversations with several of them and answered their inquires and objections; . . . a spirit of friendship has been shown by all the people.” William Yates noted that “railroad people were very kind to us in Toledo, asked many questions about the gospel.” John W. Southwell noted that, when the trains slowed down, “young people jumped off and stole fruit from orchards.” In 1857, Jesse B. Martin, en route from Toledo to Chicago, “traveled safely all night in first class carriages which were very comfortable; we retired to our beds made in the seats of the cars.”72

Whatever troubles immigrants had between 1855 and 1861 paled compared to the travel difficulties occasioned by the Civil War.73 This was the first time railroads had been used on such a large scale for military purposes. In many instances, railroads provided the only practical means to move troops and supplies; consequently, the condition of civilian travel by rail declined as the war progressed. Increasingly, travel was unreliable, equipment and passenger cars very poor, and schedules erratic. Trains could be halted for hours; routes were interrupted and changed.

In 1863, Mary C. Soffe and her company, for example, had to make eleven changes between New York City and Saint Joseph. Some had to ride in dirty cattle cars. One company in 1862 was rerouted and changed a number of times and finally hustled on board a freight train. The cars had been loaded previously with hogs, and they had not been swept or cleaned out; thus “we were choked with the dust and we could taste it for days afterwards.”74

Still another party traveled nine days and nights in cattle cars, with doors locked at night, sleeping on straw-covered floors serving as beds. In 1861 some “soldiers tried to force their way into the section where the women were. They used obscene language and the brethren had to keep guard.”75

Mormon immigrants took real chances on Missouri railroads at this time. In fact, by far the worst immigrant train travel during the Civil War was in Missouri on the H&StJ line. Not only did Missouri fight on the Union side, but Missouri also engaged in its own private civil war and consequently suffered more war action than all other states save Virginia and Tennessee.76 Because Missouri held a central position controlling much of the Mississippi River, her railroads were exceptionally important to the Union. Southern sympathizers in Missouri preferred to destroy their own railroads rather than let them fall to the Union, and it was at this time “that railroad destruction and restoration became a science.”77 Destruction started June 3, 1861, and rebels made many efforts to destroy Missouri’s three main rail lines: the Missouri Pacific, the Hannibal and Saint Joseph, and the Missouri Northern—all used by the Saints: “Bushwackers tore up the track, ditched trains, Unknown miscreants burned timbers sufficiently to weaken railroad bridges which gave way as soon as a train came upon them.”78 Immigrants also had to guard their baggage from theft by soldiers.

Along the railways, Mormons saw damage, troops on guard duty, towns laid waste by the terrible struggle, burned equipment, torn-up tracks, track relaid without ties, and “places where men had been hanged, tarred and feathered, and where trains had been robbed.”79 In 1864, Jesse N. Smith “commenced a weary journey to Saint Joseph by the wretched [H&StJ] railroad. The engine gave out several times. Saw Union solders at all the stations; heard that the country was full of Rebel guerillas.”80

Some immigrant trains smashed through barricades on the tracks. Once at Breckenridge in 1861, F. W. Blake said, “We dashed on right over it and I presume it had got completely smashed.” In 1863, Mary Soffe noted, “We ran into a place where logs had been placed to disrail the cars. I was standing up when the cars struck the logs and the jolt threw me head formost to the other side of the car among the women and children; everyone was crying and screaming. A few were hurt.”81 In 1864, according to Mary Ann Webb, “There were three sections to our train, one went over an embankment, one jumped the track, ours arrived safely in Saint Joseph.”82

Sometimes male LDS immigrants were in danger of being impressed by the Confederates, since soldiers could get a one-dollar bounty for each male so compelled. In Saint Joseph, which contained many Confederate sympathizers, the preferred method was to pin a ribbon or a badge on some male “which counted that male as being drafted into the army.”83

Mormon immigrants had to contend with trouble not only from soldiers and train crews, but also apparently from Missourians themselves. Elizabeth Staheli wrote,

When we passed through Missouri the people were so bitter against the Mormons that we had to ride in freight cars so that the people would not know that there was anyone on the trains. One night the Missourians heard that the Saints were coming, so they burned a bridge and we had to stay in the cars until the bridge was repaired. We could hear the soldiers tramping along side the train.”84

Conclusion

Mormons have a sail/rail/trail heritage that is important and interesting. It should be appreciated and studied more. All pioneers traveled in ways besides wagons. They used all available means of transportation, whether on water by ship, canalboat, or riverboat, or on land by stagecoach, horseback, railroad, or foot. Many Mormon travelers made great sacrifices and survived harrowing risks as they made their way across America to gather to Zion in the West. Their sail and rail experiences are significant but, unfortunately, often forgotten or discounted in the collective memory and surviving image of the Mormon pioneer.85

About the author(s)

Stanley B. Kimball is Professor of Historical Studies at Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville. This article is based on two papers presented before the Mormon History Association in 1992 and 1993. The author wishes to thank Conway B. Sonne for critiquing an earlier version of portions of this paper. He expresses appreciation to Howard A. Christy and Steven C. Harper for their editorial assistance.

Notes

1. This estimate is based on an analysis of immigrant accounts and statistics—especially those of Andrew Jenson and those printed in the 1975 Deseret News Church Almanac. Except where otherwise noted, all citations in this paper are to manuscripts in the Archives Division, Historical Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

2. The following statistics and conclusions are based on an analysis of Andrew Jenson’s immigration figures in “Church Emigration Book,” and a study of “Latter-day Saint Emigrants Sailing to America” in the 1976 Deseret News Church Almanac, G2–G5.

3. During 1840–41, a few other companies en route to Nauvoo, Illinois, entered the U.S. at New York City and Quebec.

4. Stanley B. Kimball, “The Mormon Trail Network in Iowa, 1838–1863: A New Look,” BYU Studies 21, no. 4 (fall 1981): 417–30; and Stanley B. Kimball, “The Mormon Trail Network in Nebraska, 1846–1868: A New Look,” BYU Studies 24, no. 3 (summer 1984): 321–36. See also Leland H. Gentry, “The Mormon Way Stations: Garden Grove and Mt. Pisgah,” BYU Studies 21, no. 4 (fall 1981): 445–61; William G. Hartley, “The Great Florence Fitout of 1861,” BYU Studies 24, no. 3 (summer 1984): 341–71; and Larry C. Porter, review of Historic Sites and Markers along the Mormon and Other Great Western Trails, by Stanley B. Kimball, BYU Studies 29, no. 2 (spring 1989): 114–17.

5. While searching for Mormon rail immigrant accounts, I thought the pickings were slim. Card catalogs, computers, bibliographies, and directories were of little help. Most of my information came from thousands of notes taken while annotating more than 950 Mormon Trail reports—scant, incomplete, vague, and erroneous records mainly. Mormons, furthermore, almost never recorded the names of the railroads they used—one has to puzzle this out from their skimpy itineraries. There are also the complications occasioned by many name changes when rail lines were bought out or merged. The rail section of this paper is based largely on a study of 143 Mormon rail/trail travel accounts of the years 1855 through 1868 and, generally, for the area between Chicago and Omaha—that is, rail travel in Illinois, Missouri, and Iowa. I have only sketched in the Mormon use of railroads east of Chicago simply because there were too many railroads to consider—366 by 1855, according to the American Railway Guide (New York: Burroughs Printer, 1855). The Mormon use of the Union Pacific railroad after 1869 is another topic entirely.

Compared to Mormon canal, river, and lake accounts, however, references to rail narratives appeared plentiful. One of the few scholars to treat the Mormon use of water travel is Conway B. Sonne in his excellent and groundbreaking Saints on the Seas (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983) and his sequel, Ships, Saints, and Mariners (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987). Most of the sail section is based on notations from 189 immigrant accounts contained mainly in the archives of the LDS Church. I would like to thank Mel Bashore for sharing his notes on water travel with me.

6. Mormons who debarked at Westport and Jefferson City initially picked up the Oregon Trail. From Fort Leavenworth and Atchison, Mormons at first tramped the Fort Leavenworth Military Road and the Oregon Trail.

7. Lucy Mack Smith, The History of Joseph Smith, ed. Preston Nibley (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1957), ch. 38; see also Lucy Mack Smith, Autobiography, and the accounts of William Smith, Martin H. Harris, and Newell K. Knight.

8. Smith, History of Joseph Smith, 204–5.

9. This quarantine office was once located on the no-longer-existing Quarantine Island in the Mississippi River just south of Saint Louis. Many Mormon immigrants refer to it in their travel accounts. Here European immigrants were screened before being allowed to land at Saint Louis. Cases of cholera were especially feared.

10. June Wood Danvers, “The History of the Descendants of Nicholas Wood,” 1849, 5–6.

11. See, for example, Jonathan Grimshaw, Journal; Thomas Evans Jeremy Sr., Diary; and Job Harker, Reminiscences.

12. Andrew Jenson, “Church Emigration Book,” 329.

13. Lorenzo Hadley, Autobiography, 1863.

14. Lars Oveson, Autobiography, 1863.

15. Times and Seasons (January 1, 1842): 654. I thank Linda Haslam for drawing this to my attention.

16. Jean Rio Griffiths Baker Pearce, Diary, 1851.

17. See, for example, Job Smith, Diary, at Special Collections and Manuscripts, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, and Elizabeth Goddard, Autobiography.

18. See Reminiscences and Diary of Mary Elizabeth Rollins Lightner, John Martin, Autobiography, and William Lindsay, Reminiscences.

19. The 1852 Saluda disaster near Lexington, Missouri, in which from 100 to 250 people—most of them LDS immigrants—died, is an example.

20. Frederick Weight, Autobiography, Utah State Historical Society, 1851, 7.

21. Rasmus Nielsen, Diary, 1854, 8. Jonathan Grimshaw from England thought the slaves were treated like cattle. The price seems incorrect.

22. James Henry Moyle, Autobiography, 1854, 10.

23. Emma Higbee, Autobiography, 1854.

24. Jean Rio Griffiths Baker Pearce, Diary, March 21, 1851, 7. At about the same time that this sister recorded her views of slavery, a brother from Scotland had a similar experience in Saint Louis: “I witnessed the sale of Negro slaves at public auction in the slave market several times, and my sympathies went out to them in their forlorn and inhuman condition. Sometimes Husbands and Wives were separated, parents from their children brothers and sisters torn away from each other, sometimes pleading to be sold together to one person, but their remonstrances and wailings fell generally on the ears of hard hearted beings destitute of any kindly or humanly feelings. Sellers, buyers, spectators alike only scoffed and laughed at their entreaties.” Richard Bee, Autobiography, 1850.

The sources reveal a few other relatively unimportant comments about blacks of that time and place. I am pleased to report that only once did the epithet nigger surface: it was expectedly in an 1864 account by a native of Saint Louis, who was “waited on by niggers” (Moroni Dunford, Journal; apparently written by a Mormon). In 1867 one English convert used the much less pejorative term “darkies,” as in “The crew was all darkies and not very sociable.” Charles K. Hansen, Record Books. Thomas Fisher, who sailed from Liverpool in 1854, recorded: “The passangers underwent medical inspection, the results terminating in the rejection of Sister Jane Hunter, from the London Conference, on the grounds of her being a coloured woman or [of] the Negro race. It appears that [in] New Orleans, the capital of the Slave State, Louisiana . . . colored persons emigrating there are liable of being kidnapped on the plea of being runaway slaves.” Thomas Fisher, Journal. One might wonder how many “colored people” in Europe became Mormons and were not permitted to emigrate.

25. See Gibson Condie, Journal, and Christian Munk, Journal. I am constantly amazed, given the difficult travel conditions of the Mormon immigrant period, how many women were either pregnant before they started west or became so en route. Obviously many husbands did not consider pregnancy of great concern.

26. See William Adams, Journal, 1844. The Maid of Iowa regularly traveled the entire distance of the river from Nauvoo to New Orleans. Most other river craft operated only on the upper Mississippi or the lower Mississippi, that is, north or south of Saint Louis. Perhaps they resented competition from the Maid of Iowa. See Donald L. Enders, “The Steamboat Maid of Iowa: Mormon Mistress of the Mississippi,” BYU Studies 19, no. 3 (1979): 321–35.

27. John E. Hill, Journal, and James L. Bunting, Diary.

28. Martin Luther Ensign, Autobiography, 1857 (April).

29. John O. Frekleton, Journal, 1862.

30. Mary Lightner, Journal, 1863.

31. Richard Rushton, Diary, 1842, 5.

32. Surely Pearce meant something like appealing, awesome, grandiose, or thrilling. Jean Rio Griffiths Baker Pearce, Diary, 1851.

33. Joseph Curtis, Reminiscences and Diary, 1854.

34. Samuel Woolley, Autobiography, 1856.

35. This childhood game/craft is still popular and is known today as “sewing cards.”

36. Elizabeth Goddard, Autobiography, 1851, 62.

37. Joseph W. Young, Diaries, 1853.

38. Samuel Amos Woolley, Diary, May 1856. Mormons, like many others of that time and period were amused, bemused, and even serious about the popular Viennese fad of phrenology, which claimed to analyze character by studying the shape and “bumps” of the skull. Heber C. Kimball, Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, and others all received readings.

39. John Nielson, Reminiscences, 1866.

40. See Joseph G. Hovey, Journal, 1837.

One year earlier, in 1836, the editor of the Messenger and Advocate traveled east from Kirtland to New York City. He sailed from Fairport, Ohio, to Buffalo, then took an Erie Canal line boat to Utica, New York, “just in time to take the rail road car for Schenectady: the first passengers’ car on the new road,” and thence to Albany by rail and down the Hudson River by boat to New York City. Oliver Cowdery to His Brother, August 3, 1836, on Board the Steamer Boston, Long Island Sound, Messenger and Advocate 2 (September 1836): 372–75.

In 1841, Mary Maughan traveled to Nauvoo from Quebec/Montreal by rail to White Hall, New York; by canalboat to Buffalo, New York; by Lake Erie steamer to Fairport; and by wagon to Kirtland and Nauvoo. That same year, William Appleby took rail and canalboats to Nauvoo. And in 1845, S. J. Raymond traveled from Long Island, New York, to Nauvoo by train, canalboat, and riverboat via Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Saint Louis.

41. Millennial Star 29 (January 19, 1867): 43.

42. Furthermore, by 1857 it was possible to reach Saint Louis by train on the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Saint Louis lines.

43. See the Contributor and the accounts of Matthew Rowan in 1855 and Thomas Evans Jeremy in 1855. Charles Shelton from Canada came this way and “jumped off” from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Territory; William Empey in 1854 returned home this way from his mission to England.

44. This was part of the Union Pacific system in 1994. See, for example, Samuel W. Richards, 1854. Beginning in 1859, some Saints also took the Missouri Northern Railroad from Saint Louis to an intersect with the H&StJ Railroad.

45. By 1854 the C&RI had reached the Mississippi at Rock Island, Illinois, a distance of 181 miles via Joliet and La Salle; and two years later, on April 21, 1856, it crossed the river to Iowa City.

46. James G. Willie Company, Journal, 1856; compare William Woodward, Journal. Samuel Openshaw took rail from Boston to Greenbush, New York; sailed the Hudson River to Albany; and took rail to Rochester and Buffalo, changing trains for Cleveland, then Toledo, then Chicago, then Iowa City.

47. LeRoy R. and Ann W. Hafen, Handcarts to Zion (Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark, 1960), 30. See also the “Thirteenth General Epistle of the First Presidency,” October 29, 1855.

48. During 1856–58, thirty-six hundred Saints, including the first seven handcart companies, took the C&RI railroad to Iowa City. See “Pioneer Companies Which Crossed the Plains, 1847–68,” 1976 Deseret News Church Almanac (Salt Lake City, 1976), G8–G22.

49. See, for example, the accounts of Mary Normington, Barbara White, Patience Rosa Archer, Thomas Durham, Peter Madsen, and William Woodward.

50. See accounts of Lucy Marie Canfield (1862) and George Cunningham (1861).

51. I have located sixty-three brief LDS accounts of this route. The CB&Q proceeded west via Princeton, Galesburgh, and Macomb, Illinois.

52. Thomas Memmott, Journal (July 1, 1862).

53. Randall H. Hewitt, Across the Plains . . . in 1862 (New York City: Broadway Publishing, 1906), 16–17.

54. Across the Plains in ’65 (Denver: Privately printed, 1905), 15.

55. Should anyone wish to follow this route today, there were twenty-nine stations along the line as follows: Hannibal, Barkley, Palmyra, Ely, Monroe, Hunnewell, Lakenan, Shelbina, Clarence, Carbon, Hudson, Bevier, Callao, New Cambria, Bucklin, Saint Catherine, Brookfield, Laclede, Meadville, Chillicothe, Utica, Breckinridge, Hamilton, Cameron, Osborn, Stewartsville, Easton, Saxton, Saint Joseph. Hannibal City Directory (n.d.), 176.

56. See accounts of Carl J. Fjeld, Henry Reiser, William Budge, Thomas C. Griggs, and William Yates.

57. Under normal conditions, which seldom pertained, the trip took eleven hours, including a thirty-minute lunch stop at Brookfield.

58. Hozial H. Baker, Overland Journey to Carson Valley and California (San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1973), 8.

59. Across the Plains in ’65, 16.

60. See, for example, Andrew Fjeld, A Brief History of the Fjeld-Fields Family (Springville, Utah: Art City, 1946) and, especially, an 1868 account by Joseph Tod Hunter, Utah State Historical Society.

61. At least 6,328 Saints went this way. See 1976 Deseret News Church Almanac. Among them were, in 1865, Joseph W. Young, Jesse Smith, Per O. Holmgren, and T. C. Grundwig (whose wife was later kidnapped by Indians); compare Kimball (see n. 4); Christian Hansen (1866); William E. Gooch; William Grant (1866); and William Mulder, Homeward to Zion: The Mormon Migration from Scandinavia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1957).

62. Among those who took this roundabout route were William Wood Sr. in 1862 and John Brown in 1868. The line later became the Wabash, then Saint Louis and Pacific, Norfolk and Western, and, currently, the Norfolk Southern. There were thirty-one stations along the 168 miles between Saint Louis and Macon: Saint Louis, Bellefontaine, Jennings, Woodstock, Ferguson, Grahams, Bridgeton, Section 16, Ferry Landing, Saint Charles, Dardeene, O’Fallon, Perseque, Wentzville, Millville, Wrights, Warrenton, Jonesborough, High Hill, Florence, Montgomery, Wellsburg, Martinsburg, Jeffstown, Mexico, Centralia, Sturgeon, Renick, Allen, Jacksonville, Macon. Hannibal City Directory, 176.

63. Joseph Tod Hunter, 1868.

64. See Zebulon Jacobs, Journal, 1868. Compare accounts by Brigham Young Jr., and Joseph S. Horn. Its route was via De Kalb and Dixon to Fulton, Illinois (just opposite Clinton, Iowa, on the Mississippi River), and thence via Cedar Rapids, Marshaltown, Ames, Carroll, and Denison to Council Bluffs.

65. The Union Pacific Railroad started west from Omaha in 1865, but the Mormons generally did not use this railroad until 1867 when the tracks reached as far west as North Platte, Nebraska. In 1868, Mormons took the Union Pacific to Cheyenne, Laramie, and Benton, Wyoming; thereafter, they took it all the way to Ogden.

66. Zebulon Jacobs, 1868 (July).

67. John Brown, for example, went this way in 1868 while traveling to Saint Louis to become the emigration agent there. As did William Hart Miles, Mormons, generally missionaries, also went east by railroad. Most of the time they followed the routes we have just noted, but occasionally they used some alternates. In 1856, Joseph Heywood traveled on the Oregon Trail to Atchison, Kansas Territory; took a riverboat to Saint Louis; then boarded the Chicago and Alton Railroad. In 1857, George Q. Cannon crossed Iowa by stagecoach to Burlington, where he picked up that branch of the CB&Q. Martin Luther Ensign followed the Mormon Trail in 1857 to Florence, took the steamboat to Saint Louis, and went by rail to New York City via Cincinnati and Philadelphia. In 1863, George M. Brown followed the Mormon Trail to Florence and took a stage to Des Moines, Iowa, where he caught the C&RI. Brigham Young Jr., going east in 1867, took the Union Pacific to Omaha, then rode the C&NW. Other typical accounts of going east by railroad are those of Samuel W. Richards, Jesse N. Smith, Hiram Spencer, Zebulon Jacobs, and John Brown.

68. The expressions of the day were “railway fatigue” and “railway spine.” See “The Pathology of a Railroad Journey,” in Wolfgang Schievelbusch, The Railway Journey (Berkeley: University of California, 1986), 113–23—an important, but rather quirky, book.

69. See accounts of B. H. Roberts, 1866; Henry Reisler; Thomas Memmott; and Joseph W. Young. Elijah Larkin tells of a child dying near Albany.

70. See Henry Stokes, 1864.

71. George Isom, 1862. See also William Yeates and Zebulon Jacobs.

72. F. W. Blake, 1861; William Yeates, 1861; John W. Southwell; and Jessie B. Martin, 1857.

73. Generally speaking, Mormons were little affected by the Civil War. In 1862, Fort Douglas was established in Salt Lake City to discourage the Mormons from possible rebellion against the Union and to protect the vital overland mail and telegraph systems linking the east and west coasts. Also in 1862, a 120-man LDS detachment guarded the mail route in central Wyoming for ninety days. The best account of Mormons and the Civil War is E. B. Long, The Saints and the Union: Utah Territory during the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1981).

On the wagon trails, immigration companies were seldom bothered by the war. There are occasional references in the sources to Mormons seeing troops guarding these vital lines of communication. Some claimed that the troops “stole cattle, swore, cursed and tried to get the young ladies.” See Miles P. Romney, Journal History, August 11, 1865. Some companies were searched for deserters and draft dodgers, and sometimes at Fort Bridger native-born males had to take an oath of allegiance to the Union, and all foreign male adults were required to swear strict neutrality. Most wagon immigrants, however, were generally little touched by the war. This was not so with the rail/trail immigrants. Their story and Civil War difficulties are a little-known chapter in Mormon history.

74. William Wood, June 1862.

75. Thomas C. Griggs, June 1861.

76. The number of Missouri engagements indicated on official records is 1,162. J. H. and Roberta Haywood, The Story of Hannibal (Hannibal, Mo.: Haywood and Haywood, 1970), 55. An excellent account of Missouri during the Civil War is Richard S. Brownlee, Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1958).

77. Margaret Louis Fitzsimmons, “Missouri Railroads during the Civil War and Reconstruction,” Missouri Historical Review 35 (October 1940): 190.

78. Fitzsimmons, “Missouri Railroads,” 193. It became a principal objective of the Union to protect the H&StJ railroad, and to this end it deployed ten thousand troops. “On every train at the major bridges, trestles and railroad facilities, soldiers were stationed. The confederates tried to destroy bridges, but were unsuccessful in other than temporary harassment of the line. The trains were frequently shot at by bushwackers, but little damage was done.” Haywood, Story of Hannibal, 55.

79. See Andrew C. Nielson, 1864, and Emma Hill, A Dangerous Crossing [Denver, 1924], 3–48; located in the Western Collection of the Denver Public Library.

80. Oliver R. Smith, The Journal of Jesse Nathaniel Smith (Provo, Utah: Jesse Smith Family Assn., 1970), 169.

81. See F. W. Blake, 1861, and Mary C. J. Soffe, 1863.

82. Mary Ann Webb, Autobiography.

83. See Thomas White, July 1863. I know of no Latter-day Saints who were actually so drafted.

84. Elizabeth Staheli Walker, Utah State Historical Society, 1861, 2. It is quite possible that Walker was mistaken in attributing their troubles to “anti-Mormons.” Many immigrants had to ride in non–passenger cars during the Civil War, and the bridge was undoubtedly burned for military reasons.

85. For those who might wish to follow some of the old rail routes west, their modern names are as follows:

• The Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad (CB&Q) is the Burlington Northern.

• The Chicago and Rock Island Railroad (C&RI) is several railroads, especially the Iowa Interstate.

• The Chicago and Northwestern Railroad (C&NW) is still the Chicago and Northwestern.

• The Chicago and Alton Railroad (C&A) is Illinois Central and Gulf.

• The Hannibal and Saint Joseph Railroad (H&StJ) is mainly part of the Burlington Northern.

• The Northern Missouri (NM) is now part of Norfolk Southern.

• The Pacific Railroad (PR) is now the Union Pacific.

Several of these railroads are now part of the Amtrak system and offer passenger service. It is possible today to ride the old Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy from Chicago to Quincy, Illinois; the old Chicago and Alton from Chicago to Saint Louis; and the old Pacific Railroad from Saint Louis to Jefferson City. A number of books and articles are available to inform the travel-minded amateur or professional about this interesting phase of travel history in western America and of the pioneer Saints.

For further information readers may wish to refer to Richard S. Jensen, “Steaming Through: Arrangements for Mormon Emigration from Europe, 1869–1887,” Journal of Mormon History 9 (1982): 3–23; Kate Carter, “People Who Came on the First Trains,” Our Pioneer Heritage (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1965); Dwight L. Agnew, “Iowa’s First Railroad,” Iowa Journal of History 48 (January 1950): 1–16; Dwight L. Agnew, “The Rock Island Railroad in Iowa,” Iowa Journal of History 52 (1954): 203–22; Homer Clevenger, “The Building of the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroads,” Missouri Historical Review 36 (1941): 32–47; Fitzsimmons, “Missouri Railroads,” 188–206; John F. Stover, Iron Road to the West: American Railroads in the 1850s (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978); Richard C. Overton, Burlington Route (New York: Knopf, 1965): Richard C. Overton, Burlington West (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1941); Robert J. Casey, Pioneer Railroad: The Story of the Chicago and Northwestern System (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1948); and Andrew M. Modelski, Railroad Maps of North America (New York: Bonanza Books, 1987). Especially helpful is a series of articles printed in 1891 in The Contributor, a Mormon monthly published in Salt Lake City.

- Sail and Rail Pioneers before 1869

- Secular Learning in a Spiritual Environment

- David White Rogers of New York

- How Large Was the Population of Nauvoo?

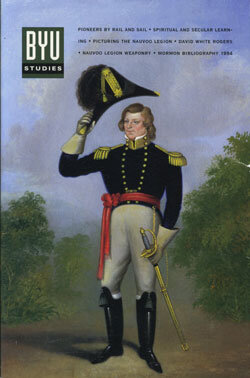

- Picturing the Nauvoo Legion

Articles

- Re-examining Baptismal Fonts (videocassette)

- The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism

- An Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton

- Eight volumes of talks from Women’s Conference at BYU

- The Angel and the Beehive

- Moral Perspectives on U.S. Security Policy

Reviews

- Historical Dictionary of Mormonism

- Catching the Vision: Working Together to Create a Millennial Ward

- The Radiant Life

- Crossing the Threshold of Hope

- Thy People Shall Be My People and Thy God My God: The 22d Annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium

- The Apostle Paul: His Life and Testimony: The 23rd Annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium

- The Father of the Prophet: Stories and Insights from the Life of Joseph Smith Sr.

Book Notices

- Mormon Bibliography 1994

Bibliographies

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X