Junius and Joseph

Presidential Politics and the Assassination of the First Mormon Prophet

Review

Robert S. Wicks and Fred R. Foister. Junius and Joseph: Presidential Politics and the Assassination of the First Mormon Prophet.

Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 2005.

In what has been called the Age of the Common Man, Andrew Jackson’s Democrats invented a new style of politics. The founding fathers, who were suspicious of political parties and omitted them from the United States Constitution, would have spun in their graves if they could have seen the parades, barbecues, and rallies that roused the party faithful for Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson. The Democrats’ opponents assembled themselves into a loose coalition of moralists, capitalists, and antislavery advocates so bereft of a unifying ideology that they had to borrow their name—Whig—from history. All they knew was that they could not stand Democrats and King Andrew. Elections became no-holds-barred battles for white male voters, who turned out in droves to cast their ballots. For the next two decades, Whigs would spar with the Democrats, winning only one decisive presidential victory and then fade into oblivion as the new Republican party formed in 1854.

It is against this backdrop of partisan warfare that the authors of Junius and Joseph stage their story. Previous works on the murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith have focused on the trial of their accused killers, the fate of the attackers, or the assassination as a pivotal event in the history of God’s chosen people. My own work analyzed the event from the point of view of Hancock County’s old settlers, particularly those in the rural areas who burned out the Mormons and drove them toward Nauvoo.

Junius and Joseph takes a new slant on an event that reveals the dark side of democratic rule, what Tocqueville is known to have called the tyranny of the majority. Ultimately, Wicks and Foister argue that it was party politics that killed Joseph Smith. Bit by bit the authors slowly lay out their argument—that political operatives present at events surrounding the charge on the jail had ties to Whig presidential candidate Henry Clay. Protagonists include George T. M. Davis, editor of the Whig Alton Telegraph; General John J. Hardin, Whig and commander of the Illinois militia assigned to keep order in Hancock County; and finally, the lowly drifter John C. Elliott, who is said to have shot the fatal bullet from a large-bore shotgun. It is an intriguing story, and putting the events in Hancock County in the context of state politics is long overdue. Thus this book is a welcome fresh look at events in 1844 that led to the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. The book’s argument, that conspiring Whigs were responsible for the death of the Mormon prophet, will join the annals of conspiracy theories so attractive to some Americans.

Readers may have trouble making their way back from political detours to the main argument, which is not sprung on the reader until page 260 in chapter 20. This rhetorical strategy of surprising the reader does generate suspense but runs the risk of driving away readers not patient enough to connect the dots. But back to the main question: Is the notion of a national-level Whig conspiracy to assassinate Joseph Smith believable? For me, the claim remains speculative because the evidence does not sustain the argument. First, the authors build their case by tracing the details of rhetoric in the party-sponsored newspapers of antebellum Illinois. Those newspapers are sharply partisan rags and are not to be taken at face value. Second, they rely on sources written decades after the event, such as a deathbed confession or biographical sketch. Third, their argument often lacks local context. For example, they claim that delegates from each state were present at a “star chamber” meeting the night before the attack. There may well have been men from many states, but because Hancock County was at a middle latitude of the nation, such an array occurred naturally as a result of migration flows. For me, the evidence is still weighted toward local concerns and political and economic jealousies that spurred a mob to form. In this dark period of democracy, many Americans viewed mobs as a legitimate solution to a problem they could not solve any other way. Because Hancock County lacked a reliable police force or militia, the Carthage and Warsaw militias had nearly free reign to impose their will.

In light of these factors, the authors assign too much weight to party affiliation as a motive in the murder plot. A Whig sold the press to William Law, but it does not follow that the Whig who sold it wanted Smith to die. And despite the efforts of men like Davis, the Whigs were not even close to winning Illinois for Henry Clay in the 1844 election, meaning the assassination (if indeed it was motivated by political rivalry) was all for naught. The Democrats won Illinois with a plurality of over thirteen thousand votes, resulting in part from the dramatic increase of over eleven thousand Democratic votes since 1840, compared to only an increase of 355 Whigs in the same four-year interval. In The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party, Michael F. Holt argues it was this surge in new voters that gave Democrats nine-tenths of their margin of victory in Illinois. Democrats took 54.4 percent of the vote in 1844, compared to 42 percent for the Whigs (the rest went to the Liberty party).1 Whigs held just one-third of the seats in the Illinois legislature; did that mean state party officials were willing to stoop to murder to put Henry Clay in the White House? Even if the one thousand or so Mormon voters had not switched their votes from Whigs to the Democrats, it would not have been enough to give Whigs the victory they so ardently desired. Making a case for murder gives little consideration for the broader context in which historical events occurred.

If historians of Mormonism are ever to join the historical mainstream, the events of Mormon history must receive more careful attention by those well trained in broader historical contexts. Only when we can show how the Mormon story matters to larger narratives will that story matter to anybody besides us.

About the author(s)

Susan Sessions Rugh is Associate Professor of History at Brigham Young University and is the author of Our Common Country: Family Farming, Culture, and Community in the Nineteenth-Century Midwest (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001).

Notes

1. Michael F. Holt, The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 197, 214.

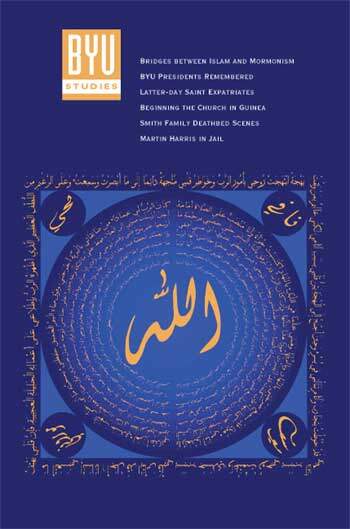

- Building Bridges of Understanding: The Church and the World of Islam

(Introduction of Dr. Alwi Shihab) - Building Bridges to Harmony through Understanding

- Alhamdulilah: The Apparent Accidental Establishment of the Church in Guinea

- “Strangers in a Strange Land”: Assessing the Experience of Latter-day Saint Expatriate Families

- Moritz Busch’s Die Mormonen and the Conversion of Karl G. Maeser

- Charting the Future of Brigham Young University: Franklin S. Harris and the Changing Landscape of the Church’s Educational Network, 1921–1926

- The Archive of Restoration Culture, 1997–2002

- The “Beautiful Death” in the Smith Family

Articles

- Astonishment

Poetry

- Sisterz in Zion

- States of Grace

- Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball

- Junius and Joseph: Presidential Politics and the Assassination of the First Mormon Prophet

- Black and Mormon

- Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet

- In All Their Animal Brilliance

- The Secret Message of Jesus: Uncovering the Truth That Could Change Everything

Reviews

- The Founders on Religion: A Book of Quotations

- The Mormon History Association’s Tanner Lectures: The First Twenty Years

- The Marrow of Human Experience: Essays on Folklore

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone