Charting the Future of Brigham Young University

Franklin S. Harris and the Changing Landscape of the Church’s Educational Network, 1921–1926

Article

Contents

Education is deeply embedded in the theology and religion of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Formal educational systems began to develop soon after the establishment of the Church in 1830. The first of these formal systems was the School of the Prophets, established in Kirtland, Ohio, in December 1832 to prepare selected members for missionary work.1 Nearly a decade later an attempt was made to establish a university in Nauvoo, Illinois. After the move to Utah, the Church continued its involvement in formal education with the establishment of “common schools, stake academies, and colleges and universities.”2 The curriculum of these early frontier schools was heavily influenced by Church attitudes and teachings. To the growing non-LDS population in Utah this intermixing of religion and education was offensive, and Utah education became a source of conflict as each group sought to influence the educational curriculum.3 This conflict influenced Church leaders to “organize experimental church schools” to educate the youth of the Church.4 This experiment assumed more urgency with the passage of the Edmunds-Tucker Act in 1887. The Edmunds-Tucker Act accelerated the growing “secularization of the public schools.”5 This, in turn, led the Church to expand its network of stake academies and colleges and begin investigating the need for a vehicle to deliver religious education to those LDS children attending public schools.6

By 1911 the Church had established a network of twenty-two high-school level academies.7 Although not formally accredited as colleges, three of these academies were authorized to conduct college work: Brigham Young University in Provo, Brigham Young College in Logan, and Latter-day Saints University in Salt Lake City.8 Eight years later the appointment of Elder David O. McKay of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles as Church Commissioner of Education (1919–1922) set in motion the first of a series of reviews of this educational network. These reviews were conducted through most of the 1920s and resulted in important policy changes that dramatically remade the Church’s educational network. The most pronounced policy change was a shift away from the academy network and toward the growing seminary program. By the end of these reviews, nineteen of the Church’s twenty-two academies had been either closed or transferred to the states of Arizona or Utah.9

Brigham Young University was fortunate to have Franklin S. Harris at the helm during this turbulent time. He successfully envisioned a new mission for BYU and changed the university’s focus from solely producing teachers for the Church’s educational network to enabling students to become leaders in the arts and sciences, government, and academia. His vision and effective advocacy for this new mission enabled the university to retain its place as the flagship of Church education at the end of the 1920s.10 Franklin S. Harris played a critical role in establishing a solid foundation that enabled BYU to survive the changing landscape of the Church’s educational network in the 1920s. This paper will examine the structures Harris put into place between 1921 and 1926 that enabled BYU to broaden its programs from teacher training to include all the disciplines associated with a first-rate university.

Changes in the Church’s Educational Policy

The new shape of the Church’s educational network began to emerge with the appointment of Elder McKay as Church Commissioner and his selection of Elder Stephen L Richards as his first counselor and Elder Richard R. Lyman as his second counselor. They recommended that outgoing Superintendent of Church Schools Horace H. Cummings be replaced by Adam S. Bennion.11 The new Commission of Education operated under the direction of Church President Heber J. Grant.12 It promptly set about evaluating the Church’s educational network. A number of concerns prompted the Commission to submit a letter to the General Church Board of Education on March 3, 1920, outlining its recommendations on the direction that Church education should take. A major concern was financial—the educational programs of the Church were becoming an increasing drain on the Church’s budget. The Commission said, “The problem of maintaining the present number of schools is a most difficult one, especially so in the light of the absolute necessity of increasing teachers’ salaries in much greater proportion than either the Church or the State has hitherto done.”13 Another major concern was the sense of duplication between academies and state-sponsored high schools.14 The steadily improving state-sponsored high schools were gaining favor with many Church members, and attendance was declining at the Church academies.

To answer those concerns, the Commission proposed that the focus of Church education shift away from the academy network in favor of the developing seminary program and that the Church close several of their academies or transfer them to the state.15 The Commission further recommended that two-year teacher training programs be established at Brigham Young University, Brigham Young College, Weber Normal College, Snow Normal College, Ricks Normal College, and Dixie Normal College. This recommendation recognized that two-year teacher training programs were already in place at some of these institutions and authorized the others to begin programs. Finally, the Commission recommended that “there should be one institution in the system at which a complete college course leading to a degree is offered and we recommend that this be the BYU at Provo. For this school, all the other normal colleges should be feeders.”16 The General Church Board of Education adopted these recommendations as policy on March 15, 1920, and began the slow process of implementing them.17

News of the policy change was upsetting to members of the communities where the academies were located. Although many of the community leaders understood the financial reasons for wanting to close selected academies, they were convinced that the academy in their community should not be closed. Superintendent Bennion worked tirelessly over the next year to convince communities that the policy was a necessary change and that the seminary program would benefit their communities even more than the academies had. He met with little initial success and had managed to convert only three academies to state-run high schools by the end of 1921.18

One community that did not need much convincing that the new policy was a good idea was Provo, home of BYU. The university had achieved the status of flagship of Church education in the late 1880s, and the new policy further solidified its position. Former BYU Presidents Cluff and Brimhall had long labored to have BYU named as the Church’s teachers’ college, and their efforts were rewarded in 1909 when the General Church Board of Education announced that “there be no college work done in the Church Schools, except what is necessary to prepare teachers, and this be done in the Brigham Young University, also that the Church Teacher’s College be established at the Brigham Young University.”19 Franklin S. Harris’s 1921 appointment as university president further bolstered confidence in BYU’s future.

A New President for BYU

The search for a new Brigham Young University president had begun in 1920 when George H. Brimhall was released. President Brimhall wanted to dedicate more time to the growing seminary program and felt he couldn’t do that and continue to serve as president of BYU.20 In early March 1920, Commissioner McKay recommended that Dr. Milton R. Bennion, then dean of the School of Education at the University of Utah, be appointed president of BYU.21 He received permission to contact Dr. John A. Widtsoe, president of the University of Utah, about procuring Dr. Bennion’s services. Later that same month Commissioner McKay reported to the General Church Board of Education that he had spoken with Dr. Widtsoe and that Dr. Widtsoe had “abstained from making any definite answer as to whether he would feel all right about letting Brother Bennion go from the University, further than to say that if the brethren thought that Brother Bennion could do better work in another position he would not stand in the way.”22 In the discussion following Commissioner McKay’s report, several members of the General Church Board of Education questioned the propriety of taking Dr. Bennion away from the University of Utah. They decided to table the issue for the time being and authorized Commissioner McKay to “make further investigation to see if some other suitable man could be secured.”23

The Commission of Education was forced to find that “other suitable man” without Elder McKay’s participation in the process because Elder McKay had left on a world tour as part of his responsibilities as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.24 The Commission of Education presented their recommendations regarding the leadership of BYU to the General Church Board of Education in mid-April. Speaking on behalf of the Commission, Elder Stephen L Richards recommended that George H. Brimhall be granted the status of president-emeritus and that Franklin S. Harris of the Utah State Agricultural College be offered the presidency of the university.25

Franklin S. Harris’s Preparation for the Presidency

Franklin S. Harris began his academic career in earnest in 1903 at the age of nineteen when he commenced high school work at Brigham Young University. He completed his high school diploma in 1904 and returned home to Colonia Juarez, Mexico, where he taught school for a year. In September 1905 his passion for learning led him back to BYU, where he commenced his college studies under the tutelage of Dr. John A. Widtsoe. His association with Dr. Widtsoe would mark the trajectory of his academic career.26 He completed his college studies at BYU in 1907 and followed Dr. Widtsoe to the Utah State Agricultural College. After teaching at the Agricultural College for one year, Harris took his new bride, Estelle Spilsbury, and moved to Ithaca, New York, to pursue graduate work in agronomy at Cornell University. Upon completion of his degree, he returned to the Utah State Agricultural College as a professor of agronomy and an agronomist on the staff of the Experiment Station. He quickly rose through the academic ranks and eventually served as director of both the School of Agricultural Engineering and the Experiment Station. He was considered for the presidency of the Agricultural College in 1916. His administrative skills and close association with Widtsoe were among the factors the General Church Board of Education considered when offering him the presidency of BYU.27

Accepting the BYU presidency was not an easy decision for Harris. He enjoyed his agricultural work at the Utah State Agricultural College and was comfortable with the career path he was following at an institution that cared as deeply about agriculture as he did. He still hoped to be president of the Agricultural College at some day in the near future.28 Moreover, he was concerned about the nature of BYU—particularly its composition of high school students mixed in with college students.29 Harris consulted with Widtsoe and other trusted advisors until he was comfortable that BYU had the potential to be a fine university. He considered the decision for a week after it was first offered to him by President Heber J. Grant, and accepted on April 22, 1921.30 The BYU Board of Trustees unanimously approved the appointment of Franklin S. Harris as university president on April 26, 1921, and set July 1, 1921, as the date that the appointment would take effect. They felt strongly that they had “the right man in the right place.”31 It was a fortunate choice for BYU. Harris gained a compelling vision of the university’s potential and was able to persuade others to believe in that vision. He was also able to begin implementing pieces of that vision in a manner that demonstrated its practicality and achievability.

Harris’s Vision for BYU’s Future

On his first visit to campus, shortly after accepting the presidency, Harris stated, “The President of the Church Commission of Education, and all who have anything to do with Church schools are determined to make this ‘the great Church University.’”32 President Harris’s vision of what was meant by “the great Church University” differed from that of his predecessors. From its inception in 1875, BYU had focused on training teachers for the Church’s educational network. While Presidents Cluff and Brimhall and the BYU Board of Trustees had envisioned the university as the primary institution of teacher training for the Church, President Harris had another purpose in mind—a purpose that would give BYU a much more stable position in the Church’s educational network.

He outlined what that purpose was during that first visit to campus in April 1921. He told the assembled student body, “All Mormondom cannot be educated here but I hope to see the time when two of a city and two of a county will come here to become leaders.”33 The purpose of the “great Church University” was to equip students with the skills necessary to be leaders in whatever discipline or field they chose to study. Harris had an expansive view of leadership. In his inaugural address he stated, “It is our purpose therefore not only to train our students in the useful arts and sciences of the day, but also to fit them to lead in various civic, religious, and industrial problems that arise out of the complex conditions of modern life.”34 He wanted BYU to produce students capable of excelling in whatever field or discipline they chose to study. These students would make the world a better place to live and would spread the ideals of the Church worldwide.

President Harris recognized that if the university were to produce students capable of standing at the front of their chosen disciplines and become “the great Church University,” several things had to occur. “We are expected to render service and our people are destined to lead the world in all things good,” he said. “We want to make this institution the greatest on earth, as it is now in many respects. It doesn’t take a big plant to be great. We want more buildings, more equipment and a greater faculty; but first of all, we want to establish pre-eminent scholarship and leadership.”35 He encouraged the faculty and the student body to join with him in a cooperative effort to make BYU truly great.

President Harris recognized immediately that he needed a plan to achieve his goals. Harris’s broad concept of leadership as encompassing excellence in a chosen discipline or field had been developing since his early experiences at BYU under the mentorship of John A. Widtsoe.36 It continued to evolve at Cornell University and the Utah State Agricultural College, where he observed the workings of Farm and Home Weeks designed to give farmers information that would allow them to improve their crop yields.37 By the time he was appointed president of BYU, Harris had come to the conclusion that leadership involved enabling individuals to reach their full potential in whatever they chose to do in life. Leadership involved teaching but was much more than that. He explained, “I believe that a person should do all he can to spread education and promote industries and occupations that will tend to make humanity more free, and give them a desire to live properly. I believe the Gospel of Jesus Christ embraces all of these principles and is a perfect code of life.”38 This progressive view of education resonated strongly with Elder McKay.39 Shortly before Elder McKay became the ninth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he summed up his lifelong view of education: “Without further comment, I give you this definition: The aim of education is to develop resources in the child that will contribute to his well-being as long as life endures.”40 Harris recognized that his vision of leadership complemented and augmented that of President McKay and spent the twenty-four years of his presidency working to enable BYU to produce students capable of being leaders in all disciplines.

Harris’s vision of the university’s potential and his desire to increase its ability to enable students to become part of the solutions to the world’s problems found support with other Church leaders as well. Soon after President Harris began articulating his new mission for the university, Elder James E. Talmage, after expressing ideas for improving the university, wrote:

I shall be glad to know as to whether the foregoing suggestions are in accord with your plan and purpose; and I assure you again that the rendering of any assistance within my power to give will be a matter of real joy as it is one of actual duty. I am sure I may say of myself and my colleagues that we, your brethren, desire to uphold your hands and sustain you in every way in the high and very important position to which you have been called.41

Harris’s first efforts were to get Brigham Young University accredited—a process that involved restructuring the academic system of the university and improving the physical plant. The support of Elder Talmage as well as President Grant, Elder Widtsoe (newly installed as Church Commissioner of Education), and others42 allowed Harris to forge ahead with his new vision for the university; their support would prove crucial to BYU’s ability to survive the changing face of Church education in the mid-1920s.

During May and June 1921, President Harris focused considerable attention on the refinement and implementation of his plan for BYU. He consulted prominent Latter-day Saint scholars about how to improve scholarship on campus and how to implement an academic structure that would meet the needs of a growing university.43 Toward the end of May, Harris began publicizing his plan with an article in the student newspaper, White and Blue. He explained the core of his vision for the university:

It is impossible in a single institution to educate all the people of the Church; other agencies are available for training the great masses. What this particular university must aim to do is to train for leadership in its highest forms: leadership in the Church itself, leadership in social affairs, leadership in business, leadership in art, leadership in citizenship, in fact leadership in all that will contribute to the betterment of the world and the happiness of its people.44

He then explained the steps that needed to be taken to enable BYU to “train for leadership.” They included:

• the need to have faculty whose scholarship was the best in the world,

• the creation of a great library,

• the establishment of a research division to aid the faculty in improving their scholarship, and

• the need for an extension division to be established in order to extend the reach of the university beyond itself.

He explained that the growth of the university needed to be slow and steady so that it would be lasting.

In his inaugural address on October 17, 1921, Harris tied the future of the university to its ability to produce leaders. “It is with the full recognition of this responsibility that Brigham Young University is laying its plans for future development. It is conscious of the fact that unless it trains men and women for leadership in the various activities in which they engage, it has no excuse for existence.”45 In this speech, Harris foreshadows the vision that Church authorities would speak about in later years, such as President Spencer W. Kimball’s statement in 1976 that BYU should aim to lead the world in scientific, intellectual, and artistic endeavors.46

Faculty and Accreditation

Strengthening the university’s faculty was one of the first challenges tackled by President Harris. He targeted faculty recruitment as the best place to start and initiated a campaign to hire faculty who held doctoral degrees or who had established strong reputations in their fields of interest.47 As part of this new recruitment policy he further stipulated that “all new faculty hold at least a master’s degree.”48 Among the faculty hired by President Harris were Harrison Val Hoyt (MA from Harvard University), L. John Nuttall Jr. (MA from Columbia University), Carl F. Eyring (PhD from the California Institute of Technology), and Melvin C. Merrill (PhD from Washington University in St. Louis).49

To encourage existing faculty members to upgrade their educational qualifications, President Harris invited them to take sabbatical leaves to enroll in advanced degree programs.50 He offered them partial salary during such sabbaticals as an incentive.51 His programs were very successful and helped improve the quality of the faculty at BYU.

President Harris understood that faculty needed the support of a strong institutional structure if they were to be successful as scholars and teachers. He also realized that the ill-defined boundary between the high school and the college was preventing BYU from becoming accredited.52 Beginning in 1922, President Harris reorganized the academic structure of the university. He organized the university into five colleges, three divisions, and a high school. He also handpicked the men to lead those colleges into the future. The colleges were the College of Commerce and Business Administration, the College of Education, the College of Arts and Sciences, the College of Applied Science, and the College of Fine Arts. The three divisions were the Extension Division, the Graduate Division, and the Research Division.53

The reorganization of BYU’s academic structure was basically complete by 1925. The changes instituted as part of the reorganization of the academic structure enabled BYU to be accredited as a college by the Northwest Association of Secondary and Higher Schools, the American Council on Education, and the Association of American Universities. The Northwest Association of Secondary and Higher Schools accredited BYU in 1923, as did the American Council on Education.54 Accreditation was an extremely important step for the university. It enabled BYU to attract more highly qualified faculty, and it allowed graduates of the university to attend prestigious graduate programs more easily. It also demonstrated to the General Church Board of Education that the university was serious in its aspirations to become the “great Church University.” Furthermore, it enabled the university to begin meeting its stated goal of producing leaders in all aspects of life.

A New Library

President Harris lobbied for a new library from the outset of his administration. Harris felt that “the library is the heart of a University”55 and that BYU could never be “the great Church university” without it. He had ramped up his campaign to get a new library built on Upper Campus56 in February 1924 with a letter to Heber J. Grant, then President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He explained that the current location of library materials was susceptible to fire damage and that it was too small to house the university’s growing library collection. He also pointed out that the library collection “is one of the most valuable collections in the West. It is particularly valuable to our people. It could not be replaced for any amount of money.”57

In May 1924, Harris learned from Elder John A. Widtsoe58 that he had “seen President Grant and talked over with him the advisability of a Library building.”59 Elder Widtsoe also advised President Harris that he would take the “matter up before the Commission of Education.”60 On August 12, 1924, Adam S. Bennion wrote to President Harris to officially inform him that the General Church Board of Education had approved the construction of a library building on Temple Hill.61 The minutes of the Executive Committee of the BYU Board of Trustees noted that the General Church Board of Education had appropriated $125,000 for the construction of the library and that Joseph Nelson had been selected as the architect. They also noted that the university hoped to raise an additional $10,000 from alumni to cover the costs of beautifying the land around the library building.62

President Harris was thrilled that the library building had been approved, and he wasted little time in sharing the news with family, friends, and colleagues. He wrote to his mother, Eunice S. Harris, “This is something I have been working for ever since I came down and so it is quite a satisfaction to have the efforts bear fruit.”63 To Fred Buss, a colleague, he exclaimed, “We were all very much elated yesterday because Wednesday the Church Board of Education decided to build us a fine library building on the hill.”64 He told his brother, Sterling Harris, “You know we have an appropriation for our new library building and we want to make the hill one beautiful spot, so are raising $10,000 from all the students in this vicinity to carry on the work.”65 The excitement surrounding the new library is best reflected in a letter written to President Harris by Eugene L. Roberts, a faculty member, during the construction of the library. Roberts wrote, “A library upon the hill and a beautiful recreational and social center nearby surrounded with courts, lawns, fields—then the extra-curricula[r] life of the school will be held in the unified grip of an ideal college settting [sic].”66

Groundbreaking for the new library was held on October 16, 1924, and the building was dedicated one year later. It was named after President Heber J. Grant to honor his commitment to education and learning.67 The building was two stories high and contained office space and classrooms in addition to closed stacks for the library collections and a large reading room.68 The new library building was also used to house the university’s Ancient American Collection in an environment that was secure, yet still available to serious scholars.69 President Harris felt that the new library was a successful addition to the campus and that it boosted scholarship of both faculty and students. To Elder Melvin J. Ballard he wrote, “The spirit of the school has never been better than this year [1926] and our new library building adds a great deal to the general spirit of scholarship.”70

Harris’s Proposal for a New Building Program

Another signal of the strength of BYU’s aspirations toward greatness was President Harris’s plan to establish adequate physical facilities for the university. In the late fall of 1925, four years into his presidency, Harris put together a report entitled “A Program for the Brigham Young University.” Prepared at the request of Superintendent Bennion, the report outlined the steps President Harris felt were necessary to put the university on a more solid footing. The report highlighted the progress made in improving the university and enunciated a plan for future development. Embedded within the plan were the structures Harris felt were needed to allow the university to become an institution capable of producing graduates who could reach the pinnacle of their chosen discipline or field. The report was favorably received by Church leadership and strengthened their commitment to helping Harris achieve his vision for the university.

President Harris used the report to highlight BYU’s progress toward becoming the “great Church University” and to explain the future needs of the growing institution. He tied the success of the university’s goals to the Church by writing that “the Brigham Young University is essentially a Church institution and it will probably always derive the greater part of its funds directly from the Church.”71 The rest of the report examined the university in five sections: organization, enrollment, greatest needs, building program, and annual maintenance.

Organization. President Harris explained that the university was now organized in three divisions and five colleges. He felt that “the Institution is in good condition in this respect and that the framework of colleges and deparments [sic] will need very little change for the next half dozen years.”72 The organizational structure had enabled the university to obtain accreditation and was handling the needs of the student body quite well.

Enrollment. President Harris highlighted the growth of the college student body: “In 1919–20 it was 428; whereas in 1924–25 it was 1204; and this year there seems to be about a 15 per cent increase over last.”73 He attributed the growth in student population to the growing excellence of BYU. He believed that the enrollment could double before the organizational structure of the university would need to be changed again.

Greatest Needs. Harris set goals for: “(1) An improved faculty, (2) More adequate scientific equipment, and (3) More books in the library.”74 He pointed out that faculty hiring was one of the most important things a university does, and he raised the question of increasing salaries to compete for better-qualified faculty.75 He believed that the “modern institution must have the apparatus of the modern world” and that BYU had made a good start in this direction but still had room to improve. He stated that “large sums” should be spent to improve BYU’s scientific equipment. He acknowledged that the Church had already generously paid for the construction of a library,76 but the library collection was inadequate and needed to triple in size.77

In order to increase the size of the library collections, Harris implemented a book drive in connection with the construction of the new library. The drive was highly successful. After just two months, over three thousand volumes had been donated to the university and over two thousand dollars had been contributed to purchase needed materials. The list of donors was impressive and showed the wide reach of the young institution, with donations coming from Oregon, Arizona, New Mexico, Idaho, New York, and Wyoming as well as Canada.78 The library continued to grow throughout Harris’s administration.

Building Program. According to President Harris, “Every growing institution must have a building program.” He felt that BYU’s building program needed to include: “(1) A library, (2) A thoroughly modern science building, (3) A gymnasium, (4) A women’s building, and (5) A class room building to house such subjects as English, History, etc.”79 Only the library building was built during Harris’s administration because of the financial situation of the Church.80 However, all of these buildings were completed following Harris’s administration as the financial situation of the Church improved and it was able to spend more money on its educational programs.81 Franklin S. Harris’s foresight and planning laid the groundwork for the successful expansion of BYU’s physical plant in the 1950s and 1960s.

Annual Maintenance. In this section of the report, President Harris argued that the appropriation for BYU needed to increase $16,000 a year for six years until it reached an annual appropriation of $300,000 a year.82 This would enable the university to meet its full potential. The Church’s poor financial position did not permit an increase to the appropriation, and it stayed flat at $200,000 a year for most of the 1920s and some of the 1930s—even as university enrollment continued to grow.

The 1926 Review of Church Schools

The rest of President Harris’s vision to make BYU the “great Church University” was put on hold for the duration of his administration because of circumstances beyond his control. A serious depression in Utah followed the end of World War I as both the mining and the farming industries collapsed due to decreased demand for their products.83 The financial struggles of the average Utahn created financial problems for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which derived much of its income from tithing revenues. The financial problems caused by the onset of the depression in Utah coupled with the economic advantage of switching from the academies to seminaries had led the Church to withdraw from high school education beginning in 1920. Continued economic problems and the growing success of the seminary program led to another review of the Church’s educational network in 1926.84 Early in the year the General Church Board of Education asked Superintendent Bennion to put together a report on the Church’s educational network. They also requested recommendations on potential directions the Church’s educational network could take.

Superintendent Bennion presented his report, entitled “An Inquiry into Our Church School Policy,” to the General Church Board on February 3, 1926.85 Bennion opened his report by noting that both the Brigham Young College in Logan, Utah, and Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho, had requested permission to expand their educational programs. He pointed out that the request of the Brigham Young College was the more reasonable one for financial reasons: “This institution can clearly extend the field of its service with a relatively nominal increase in its expenditures.” With respect to the request that Ricks College be granted four-year status from its current junior college status, Bennion wrote, “Were the Ricks College to become a senior college it would call for a substantially increased budget along with a building program of significant proportions.” He then pointed out that the “other schools in our system if they are to keep pace with similar institutions operated by the State will have to look forward to a considerable, continuing increase of outlay in the next ten years.” He made special reference to BYU and highlighted many of the elements of growth pointed out in Franklin S. Harris’s “Program for Brigham Young University.” He continued by briefly describing the history of the Church’s educational program and the gradual emergence of a competitive state-run educational system.86 The emergence of the state school system had led directly to the closure of twelve academies by 1924.87 It had also led to the growth of the seminary program. Bennion mentioned that by 1926 the Church was operating “59 seminaries, which to date are serving 9,231 students.”88

The General Church Board had a decision to make. Would they expand their network of higher education at the expense of the growing seminary program, or would they curtail the growth of their higher education program to allow the continued development of the seminary program? The seminary program was a better financial investment for the Church. It was reaching more students than the colleges for the same amount of money, and it had the potential to reach college students through the new institute program.89 Bennion suggested that the Church had three alternatives: (1) it could maintain the schools at their current level of funding and continue expanding the seminary program, (2) it could increase the funding level of the Church schools, or (3) the Church could “withdraw from the field of academic instruction altogether and center our educational efforts in a promotion of a strictly religious education program.”90 Superintendent Bennion favored the third plan because it would allow the Church to “complement the work of the entire public school system wherever our people are” and it had the potential to be considerably less expensive in the long run.91

The General Church Board carefully considered the three alternatives that Superintendent Bennion had presented. Members of the General Church Board raised several questions about the benefits of the seminary program as well as about the desirability of having a strong institution of higher education as part of the Church’s educational network. Among the questions raised were:

Does the Church receive benefit in returns from an 8 to 1 investment in Church Schools as against Seminaries?

Does there lie ahead in the field of the Junior College the same competition with State institutions that has been encountered in the high school field?

Can the Church afford to operate a university which will be able creditably to carry on as against the great and richly endowed universities of our land?

Will collegiate seminaries be successful?92

It was eventually decided that the issue was of such significance that the members of the General Church Board should be given time to seriously consider the implications of their decision and that they would continue the discussion at their next meeting.93

They next met on March 3, 1926, to consider the proposed budget for the Church schools. After Brigham Young College President W. W. Henderson presented his case that that institution should be allowed to become a four-year college, the General Church Board returned to their discussion of the general policy of the Church’s educational network.94 This discussion continued over the next several General Church Board meetings, including one in which the presidents of the various institutions that would be affected were invited to participate.95 The General Church Board spent most of the month of March debating the issue without coming to a resolution. Toward the end of the month the General Church Board asked Superintendent Bennion and the First Presidency of the Church to formulate a policy and implement it.96 On March 31, Bennion announced to the Board of Trustees of Brigham Young College that “in face of all developments, it is thought wise that we discontinue our academic program and turn our attention to religious education.”97 In April 1926, Superintendent Bennion reiterated the changing focus of Church education when he told the Board of Trustees of Snow College that “the Church had established a policy to eventually withdraw from the academic field.”98 It does not appear that Superintendent Bennion took this decision back to the General Church Board for ratification, and subsequent events indicate that the policy was not as inflexible as it first appeared.99 However, the initial implementation of the policy led many to assume that the Church truly was going to completely withdraw from the field of higher education.

The Closure of Brigham Young College in Logan

The Church began implementing the new policy in the spring of 1926 with closure of the Brigham Young College. The Brigham Young College had been founded in Logan, Utah, by Brigham Young on July 24, 1877. President Young had set aside almost 10,000 acres as an endowment for the new school.100 He hoped that the school would be established on this land and that students would work the land. The products produced by the students would then be sold to support the school. This plan never materialized, and by the opening of the 1884–85 school year the Brigham Young College was located in the “East Building” at 100 West and 100 South in Logan. Eventually other buildings were built in this same location and it became the permanent home of the Brigham Young College.101 The Brigham Young College offered a four-year baccalaureate degree from 1894 to 1909. In 1909 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints decided to eliminate upper division work at the Brigham Young College and turned it into a junior college.102 Because the legislature had prohibited the Utah State Agricultural College from offering teacher training beginning in 1905, the Church allowed the Brigham Young College to maintain a normal school along with its junior college offerings.103 The loss of the baccalaureate degree in 1909 in combination with competition from the Utah State Agricultural College proved fatal to the Brigham Young College when the Church decided to pull away from postsecondary education in 1926. President W. W. Henderson remarked at the closing of the school, “The total enrollment this year was 323. This is the lowest enrollment in twenty years. It must be remembered, however, that the policy of the college was reduced a few years ago to very unnatural and unreasonable limitations. It is now a two year school with limited preparatory facilities comparable to the fourth year of the high school.”104 He clearly felt that the loss of the baccalaureate degree in 1909 had played a major role in the Church’s decision to close the college.

Alumni and faculty attempted to make sense of the closing of their beloved school during the final commencement exercises held on May 23, 1926. President W. W. Henderson commented:

The institution is now to be permanently closed, not because of internal disintegration, but to give greater opportunity for the growth of the seminary movement. If this movement is worth enough to warrant the closing of an institution of such established value as the Brigham Young College it is most certainly one of the greatest movements in religious education.

Henderson went on to question whether the trade-off was really worth it.105 Dr. Joseph A. Geddes, a BYC faculty member, directed part of the blame at the Utah State Agricultural College. “Brigham Young did not know as President Grant does know that another large college would grow up in Logan. Those who are alive now perceive duplication and unnecessary expense in the maintenance of two colleges.” He also blamed the Church’s “policy of delimitation” that had led to a decline in the number of students, faculty, and courses offered at the Brigham Young College.106

Persistent Fears of BYU’s Closure

The news of the closing of Brigham Young College created considerable concern among faculty and others associated with BYU. Although BYU did not have to compete with a state-sponsored college in Provo, it did have to worry that Church education funds would be poured into the developing seminary program and the fledgling institute program.

President Harris worked diligently to calm the fears of faculty and others associated with BYU. Harris had good reason to believe that the new policy advocated by Superintendent Bennion was not as firm as it appeared. He realized that the new philosophy at BYU and the structures put in place to support it had strengthened the university’s role in the Church’s educational network. He also understood that members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles including John A. Widtsoe, James E. Talmage, and David O. McKay still strongly believed that the Church needed some representation in the field of higher education and that they had influential voices on the General Church Board. He wrote Melvin C. Merrill, a faculty member, expressing his optimism about BYU’s chances of survival. “There has been considerable discussing of the whole Church School System this year. This resulted in the closing of the B.Y.C. as you know and the whole thing has taken a good deal of time. It has therefore, delayed us in getting our own budget. Everything seems now in the clear for the B.Y.U. however.”107 Rumors persisted that BYU was to be closed, and, in June, Professor Merrill expressed his concerns to Harris: “From recent visitors from Logan I have understood that Dr. Adam Bennion made the statement to the B.Y.C. faculty that the new church school policy contemplates doing away with the Church schools and that the Ricks, the Weber, and the B.Y.U. are soon to go. I can’t believe that is true of the B.Y.U. How about it?”108 Harris responded to Merrill by saying:

Regarding these rumors about Institutions closing, it may be that one or two more of them will close but I think there is no chance of the B. Y. U. closing in my day or yours. Dr. Bennion did talk a little freely but he is not talking that way now and there is no sentiment among any of the general authorities (I am informed from the very best authority) to close the B. Y. U.109

The rumored closing still had legs in July as evidenced by a letter written from Harris to the editor of the Banyan:

I believe your slogan “This is the Place” for an edition of the Banyan would be unusually appropriate and as to the rumor of the closing of the B.Y.U. this is something that develops out of the closing of the B.Y.C. and I am sure from those who would know, that there is nothing definite in the rumor. The B.Y.U. is certainly in a more substantial place than it has ever been.110

The rumors were finally put to rest when Harris demonstrated his confidence in the university’s future by leaving on a yearlong tour of the world in August 1926.111

The Legacy of Franklin S. Harris

Franklin S. Harris’s ability to articulate a new vision for the university was certainly a major reason for the Church’s decision to not close Brigham Young University in 1926. By changing the focus of the institution from solely producing teachers for the Church’s educational network to enabling students to become leaders in the arts and sciences, government, and academia, President Harris gave new focus to BYU and ensured that it would always have a continuing purpose in the Church’s educational network. By demonstrating to Church leaders such as President Heber J. Grant, Elder David O. McKay, Elder James E. Talmage, Elder Joseph Fielding Smith, and Elder John A. Widtsoe that BYU was capable of fulfilling the new vision and by gaining their support, Harris ensured that the university would survive. A comment by Elder Widtsoe reflects the support Harris had garnered from Church leadership. He wrote, “Your candidates for the Bachelor’s degree, totaling about 168, as I counted them, is an indication of the complete change, during the last few years, in our educational endeavors in behalf of the public at large and of the new service which is being rendered by the Brigham Young University. If any man in our Church should be happy in the success that has attends [sic] such service, you should be that man.”112

Harris also tied the fate of the university to the growing seminary program by highlighting the university’s role in producing teachers qualified to teach seminary. In a 1930 article in the Deseret News, Church Commissioner of Education Joseph F. Merrill wrote that one of the reasons BYU had not been closed along with the rest of the schools in the academy network was that “[a] university [is] an essential unit in our seminary system. For our seminary teachers must be specially trained for their work. The Brigham Young university is our training school.”113

Equipping students to take the lead in solving world problems and producing teachers for the Church’s seminary program were not the only things President Harris did that enabled Brigham Young University to escape the fate of Brigham Young College. He also succeeded in getting the school accredited on a static budget—proving that the Church could afford to operate a successful university. Accreditation was the result of Harris’s efforts to strengthen the educational qualifications of the faculty and his reorganization of the academic structure of the university. It was also directly tied to Harris’s successful campaign to construct a library building. President Harris’s thoughtful “Program for Brigham Young University” illustrated ways that the university could meet its full potential and convinced Church leaders that maintaining a Church university was both achievable and desirable.

Franklin S. Harris was the right man at the right place, and his calm leadership enabled the university to survive the reorganization of the Church’s educational network. It also ensured that when the question of whether or not to close BYU came up again in 1929 and 1945, the answer was never in doubt—BYU would not close. His vision of the university’s potential as the “great Church University” and his actions to make that vision a reality put BYU on solid footing. The university’s current mission statement says, “All instruction, programs, and services at BYU, including a wide variety of extracurricular experiences, should make their own contribution toward the balanced development of the total person.”114 The purpose of Brigham Young University is to enable students to meet both personal and global challenges in creative ways that leave the world a better place. Brigham Young University still strives to meet the expansive definition of leadership first articulated for it by Franklin S. Harris.

About the author(s)

J. Gordon Daines III is the Brigham Young University Archivist and Assistant Department Chair, Manuscripts, in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections of the Harold B. Lee Library. He earned his BA from Brigham Young University, his MA from the University of Chicago, and did his archival training at Western Washington University. He wishes to thank Russell C. Taylor and Brian Q. Cannon for their insightful comments and thoughtful criticism of this article. Any errors are the responsibility of the author.

Notes

1. Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Knopf, 2005), 210–11.

2. Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930 (Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 157. Among the colleges and universities established were the University of Deseret (which became the University of Utah), Brigham Young College, and Brigham Young Academy.

3. For more information on the conflict between LDS and non-LDS perspectives on education and the development of the private educational system of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints see John D. Monnett Jr., “The Mormon Church and Its Private School System in Utah: The Emergence of the Academies, 1880–1892” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 1984).

4. Monnett, iv.

5. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 157.

6. The vehicle that the Church eventually decided on was seminaries and institutes. The seminary program had its genesis in 1911 with Joseph F. Merrill. Classes were first held in 1912 with completion of a seminary building next to Granite High School in Salt Lake City. Scott C. Esplin, “Education in Transition: Church and State Relationships in Utah Education, 1888–1933” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 2006), 137–39; Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 168.

7. Royal Ruel Meservy, “A Historical Study of Changes in Policy of Higher Education in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” (EdD thesis, University of California at Los Angeles, 1966), 265–66. There is no definitive answer as to how many academies the Church actually ran in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For purposes of this paper the academies counted are those with physical plants.

8. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 158.

9. Arnold K. Garr, “A History of Brigham Young College, Logan, Utah” (MA thesis, Utah State University, 1973), 75; Ernest L. Wilkinson, ed., Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years, 4 vols. (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 2:14.

10. The reorganization of the Church’s educational network and the divestment of the academy system in the 1920s are covered in Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years; and Janet Jenson, The Many Lives of Franklin S. Harris (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Print Services, 2002). Neither of these books ties the new mission for the university advocated by Franklin S. Harris to its ultimate survival during these trying times.

11. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:3.

12. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:5. The Church Commission of Education consisted of the Commissioner of Education, his two counselors, and the Superintendent of Church schools. The Superintendent of Church schools served as the executive officer of the Commission. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:4–13.

13. Minutes of the General Church Board of Education of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter General Church Board), March 3, 1920, in Kenneth G. Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion, Superintendent of L.D.S. Education, 1919–1928” (MRE thesis, Brigham Young University, 1969), 52. The minutes of the General Church Board of Education of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are closed to research currently. These minutes were available to Kenneth G. Bell in the 1960s, and excerpts are quoted from his master’s thesis.

14. Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 52–53.

15. These included Emery Academy, Murdock Academy, St. Johns Academy, Cassia Academy, Millard Academy, Uintah Academy, Gila Academy, Snowflake Academy, Fielding Academy, and possibly Oneida Academy. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:14.

16. Minutes of the General Church Board, March 3, 1920, in Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:14. The minutes of the General Church Board of Education of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are closed to research currently. These minutes were available to the research team writing the Wilkinson centennial history, and excerpts are quoted from this history.

17. Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 55.

18. Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 55–57. Those academies were Cassia, St. Johns, and Knight.

19. Minutes of the Executive Committee of the Brigham Young College Board of Trustees, May 21, 1909, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City (hereafter cited as Church Archives).

20. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:3.

21. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:16.

22. Minutes of General Church Board, March 31, 1920, in Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:16–17.

23. Minutes of General Church Board, March 31, 1920, in Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:17.

24. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:17.

25. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:17.

26. For more information on the life and career of John A. Widtsoe, see Alan K. Parrish, John A. Widtsoe: A Biography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003).

27. Jenson, Franklin S. Harris, 25–55.

28. Harris did become president of the Utah State Agricultural College in 1945 when he left Brigham Young University. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:402–4.

29. For the 1919–20 school year, Brigham Young University had 438 college students and a large number of conditional students (students not fully prepared for college work) as well as a sizeable group of high school students. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:47.

30. Franklin S. Harris, Diary, 1908–54, April 15–22, 1921, University Archives, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah (hereafter cited as Perry Special Collections).

31. Minutes of the Brigham Young University Board of Trustees, April 26, 1921, University Archives, Perry Special Collections.

32. “Dr. Harris, Pres.-Elect Visits School,” White and Blue, May 4, 1921, 1, University Archives, Perry Special Collections.

33. “Dr. Harris, Pres.-Elect Visits School,” 1.

34. Franklin S. Harris, “Inaugural Address,” in John W. Welch and Don E. Norton, eds., Educating Zion (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 1996), 7.

35. “Dr. Harris, Pres.-Elect Visits School,” 1.

36. Jenson, Franklin S. Harris, 28.

37. Jenson, Franklin S. Harris, 42, 46, 50, 74.

38. Franklin S. Harris, “Code of Life,” in Jenson, Franklin S. Harris, frontispiece.

39. For more information on the progressive nature of David O. McKay’s educational thought, see Mary Jane Woodger, “David O. McKay’s Progressive Educational Ideas and Practices, 1899–1922,” Journal of Mormon History 30 (Fall 2004): 208–48.

40. David O. McKay, Gospel Ideals: Selections from the Discourses of David O. McKay, Ninth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1998), 436. For more information, see Mary Jane Woodger, “Educational Ideas and Practices of David O. McKay, 1880–1940” (EdD diss., Brigham Young University, 1997); and Gregory A. Prince and William Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005).

41. James E. Talmage to Franklin S. Harris, June 10, 1921, Franklin S. Harris Presidential Records, 1921–45, University Archives, Perry Special Collections.

42. Heber J. Grant to Franklin S. Harris, November 22, 1921; John A. Widtsoe to Franklin S. Harris, July 20, 1922; Susa Young Gates to Franklin S. Harris, June 19, 1924, all in Harris Presidential Records.

43. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:32–35. Among those he consulted were John A. Widtsoe, president of the University of Utah, and Harvey Fletcher, a prominent LDS physicist.

44. Harris Writes on Future of School,” White and Blue, May 25, 1921, 1, University Archives, Perry Special Collections.

45. Franklin S. Harris, “Inaugural Address,” 7.

46. Spencer W. Kimball, “Second Century Address,” in “Climbing the Hills Just Ahead: Three Addresses,” in Educating Zion, 63–75.

47. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:32.

48. Gary James Bergera and Ronald Priddis, Brigham Young University: A House of Faith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1985), 15.

49. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:97–101.

50. Between 1924 and 1928, sixteen faculty members took advantage of the leave system to improve their academic credentials. Five completed doctoral degrees, and eleven completed master’s degrees. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:140.

51. Jenson, Franklin S. Harris, 77. Among the faculty who took advantage of the leave system were Florence Jepperson Madsen, Melvin C. Merrill, and Franklin Madsen.

52. From its establishment in 1875, Brigham Young Academy had focused primarily on elementary and high school education as well as teacher training. It was only in the 1920s that college work began to become the primary focus of the institution. One of the problems that Harris faced in getting the university accredited was the fact that the high school and college students were intermingled in the various classes offered by the university—there was no clear delineation about what were college courses and what were high school courses.

53. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:97–102, 117.

54. The Association of American Universities accredited Brigham Young University as a university in 1928. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:144.

55. Franklin S. Harris, “A Program For the Brigham Young University,” in Minutes of the Brigham Young University Board of Trustees meeting, December 11, 1925, 3; University Archives, Perry Special Collections. The report was given to Superintendent Bennion on November 12, 1925, 3.

56. “Upper Campus” refers to the buildings constructed on Temple Hill. “Lower Campus” refers to the buildings on Academy Square.

57. Franklin S. Harris and the Executive Committee of the Brigham Young University Board of Trustees to President Heber J. Grant, February 6, 1924, Harris Presidential Records.

58. Elder Widtsoe had become Church Commissioner of Education in 1922 when Elder David O. McKay had resigned. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:60.

59. Elder John A. Widtsoe to Franklin S. Harris, May 19, 1924, Harris Presidential Records.

60. Widtsoe to Harris, May 19, 1924.

61. Adam S. Bennion to Franklin S. Harris, August 12, 1924, Harris Presidential Records.

62. Minutes of Executive Committee of the Brigham Young University Board of Trustees, August 18 and September 10, 1924, University Archives, Perry Special Collections.

63. Franklin S. Harris to Eunice S. Harris, August 18, 1924, Harris Presidential Records.

64. Franklin S. Harris to Fred Buss, August 8, 1924, Harris Presidential Records.

65. Franklin S. Harris to Sterling Harris, August 25, 1924, Harris Presidential Records.

66. Eugene L. Roberts to Franklin S. Harris, May 30, 1925, Harris Presidential Records.

67. Augusta W. Grant to Franklin S. Harris, September 5, 1925; Franklin S. Harris to Augusta W. Grant, September 8, 1925, both in Harris Presidential Records.

68. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:64.

69. Franklin S. Harris to Professor G. Oscar Russell (Department of Romance Languages, Ohio State University), February 11, 1926, Harris Presidential Records.

70. Franklin S. Harris to Melvin J. Ballard, January 8, 1926, Harris Presidential Records.

71. Harris, “Program for the Brigham Young University,” 1.

72. Harris, “Program for the Brigham Young University,” 1.

73. Harris, “Program for the Brigham Young University,” 2.

74. Harris, “Program for the Brigham Young University,” 2.

75. In 1921, Brigham Young University employed seventy-four individuals, two of whom were classified as administrators. By 1930 there were 109 individuals employed at the university, and there were still only two classified as administrators. Of the seventy-two faculty members in 1921, only one had a doctoral degree and approximately eleven had master’s degrees. By 1930, 15.5 percent of the faculty had doctoral degrees. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:113, 125, 260–61.

76. Harris, “Program for the Brigham Young University,” 4.

77. Harris, “Program for the Brigham Young University,” 3.

78. A. Rex Johnson to Franklin S. Harris, September 28, 1925, Harris Presidential Records.

79. Harris, “Program for the Brigham Young University,” 3–4.

80. Utah was in the midst of an agricultural depression that would eventually encompass the entire United States and become known as the Great Depression. Dean L. May, Utah: A People’s History (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), 173.

81. For detailed coverage of the building program under Howard S. McDonald, Ernest L. Wilkinson, and Dallin H. Oaks, see Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, vols. 2–4.

82. Harris, “Program for the Brigham Young University,” 4.

83. May, Utah: A People’s History, 173.

84. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:68.

85. Adam S. Bennion, “An Inquiry into Our Church School Policy,” Minutes of the General Church Board of Education meeting, February 3, 1926, in Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 81–86.

86. Bennion, “Inquiry into Our Church School Policy,” 82–86.

87. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:69.

88. Bennion, “Inquiry into Our Church School Policy,” 84.

89. According to Bennion’s report, the Church schools cost $204.97 per capita and the seminaries cost $23.73 per capita. This is nearly a 9 to 1 ratio in favor of the seminary program. Bennion, “Inquiry into Our Church School Policy,” 85.

90. Bennion, “Inquiry into Our Church School Policy,” 85.

91. Bennion, “Inquiry into Our Church School Policy,” 86.

92. Minutes of the General Church Board, February 3, 1926, in Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 86–87.

93. Minutes of the General Church Board, February 3, 1926, 87.

94. Minutes of the General Church Board, March 3, 1926, in Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:72.

95. Minutes of the General Church Board, March 3, 1926; March 10, 1926; March 18, 1926; and March 23, 1926, in Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 87–91; Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:73.

96. Minutes of the General Church Board, March 23, 1926, in Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:76.

97. Minutes of the Executive Committee of the Brigham Young College Board of Trustees, March 31, 1926, Church Archives.

98. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:76.

99. See the General Church Board minutes available in Bell and Wilkinson. Although a number of schools were closed or transferred to state governments, Brigham Young University was not the only school to escape closure. Both LDS Business College in Salt Lake City and Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho remained open.

100. Garr, “History of Brigham Young College,” 5.

101. A. J. Simmonds, Register to the Papers of Brigham Young College, 1877–1960, ca. 1969, Special Collections and Archives, Merrill-Cazier Library, Utah State University, Logan, Utah.

102. Garr, “History of Brigham Young College,” 46–47.

103. Simmonds, Register; see also Alan K. Parrish. “Crisis in Utah Higher Education: The Consolidation Controversy of 1905–07,” Utah Historical Quarterly 62, no. 3 (1994): 208.

104. W. W. Henderson, “The President’s Report,” Brigham Young College Bulletin Final Volume Final Number, 18, Papers of Brigham Young College, 1877–1960, Special Collections and Archives, Merrill-Cazier Library.

105. W. W. Henderson, “The President’s Report,” Brigham Young College Bulletin Final Volume Final Number, 18.

106. Joseph A. Geddes, “History,” Brigham Young College Bulletin Final Volume Final Number, 59.

107. Franklin S. Harris to Melvin C. Merrill, May 6, 1926, Harris Presidential Records.

108. Melvin C. Merrill to Franklin S. Harris, June 10, 1926, Harris Presidential Records.

109. Franklin S. Harris to Melvin C. Merrill, June 14, 1926, Harris Presidential Records. From comments made in Harris’s journal and correspondence in Harris’s presidential records, it appears that the “very best authority” is John A. Widtsoe.

110. Franklin S. Harris to Julius V. Madsen, July 13, 1926, Harris Presidential Records.

111. Wilkinson, First One Hundred Years, 2:77–85. President Harris had been invited to speak at the third Pan-Pacific Science Congress in Japan in the fall of 1926 and decided that this would be a good opportunity to do a world tour visiting educational institutions to gain ideas for improving Brigham Young University. He was given permission to go by the General Church Board of Education as long as he conducted Church business along the way. He left in August 1926 and returned in August 1927.

112. John A. Widtsoe to Franklin S. Harris, June 15, 1928, Harris Presidential Records.

113. Joseph F. Merrill, “Brigham Young University, Past, Present and Future,” Deseret News, December 20, 1930, 3.

114. “BYU Mission Statement,” http://unicomm.byu.edu/about/mission/ (accessed November 17, 2005).

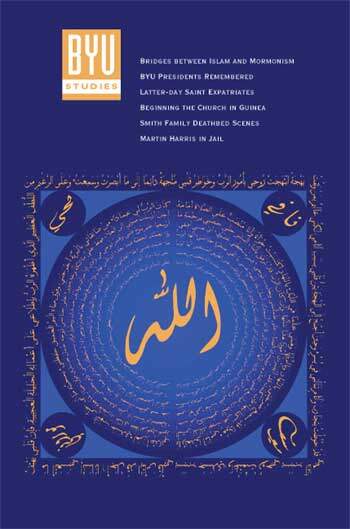

- Building Bridges of Understanding: The Church and the World of Islam

(Introduction of Dr. Alwi Shihab) - Building Bridges to Harmony through Understanding

- Alhamdulilah: The Apparent Accidental Establishment of the Church in Guinea

- “Strangers in a Strange Land”: Assessing the Experience of Latter-day Saint Expatriate Families

- Moritz Busch’s Die Mormonen and the Conversion of Karl G. Maeser

- Charting the Future of Brigham Young University: Franklin S. Harris and the Changing Landscape of the Church’s Educational Network, 1921–1926

- The Archive of Restoration Culture, 1997–2002

- The “Beautiful Death” in the Smith Family

Articles

- Astonishment

Poetry

- Sisterz in Zion

- States of Grace

- Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball

- Junius and Joseph: Presidential Politics and the Assassination of the First Mormon Prophet

- Black and Mormon

- Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet

- In All Their Animal Brilliance

- The Secret Message of Jesus: Uncovering the Truth That Could Change Everything

Reviews

- The Founders on Religion: A Book of Quotations

- The Mormon History Association’s Tanner Lectures: The First Twenty Years

- The Marrow of Human Experience: Essays on Folklore

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X