Rebaptism in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Article

Contents

The first day of November 1847 brought Patty Sessions a snowstorm that blew her tent down and shredded it. But life in Winter Quarters was never easy, and Sessions maintained her regular schedule despite the disruption. She was a midwife and had a central position among the women of the city. Over the next week alone, she delivered four babies and attended four meetings. She also sewed for hire, and she anointed and blessed in faith. And on Friday the 26th, as she wrote in her diary, “I was baptized.”1 In this short three-word entry, Sessions documented one of the most distinctive beliefs and practices of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: the repeat baptism of believers.

There are few clues to help us discern the reason Patty Sessions stepped out into the cold to be immersed in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. What is clear, however, is that Sessions was already a baptized member in good standing. Like all Latter-day Saints who lived at that time, she was rebaptized and certainly would be again, perhaps multiple times, before she passed away. And while dramatically different today, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints maintains rebaptism practices that distinguish it from nearly all other Christian groups.

Whether it is an 1893 monthly fast meeting in which “the time was all taken up confirming persons who’d been baptized—many of them rebaptized,”2 or a missionary in 1877 Ohio who rebaptized as many people as he baptized,3 documentation for the practice throughout the nineteenth century is ubiquitous. Rebaptism of Church members was practiced in four core modalities: (1) for healing, (2) as a function of Church discipline, (3) voluntarily for the remission of sins, and (4) for the renewal of covenants.4 Kristine Wright and Jonathan Stapley have written on baptism for healing in detail elsewhere, tracing its trajectory from its formal beginnings in Nauvoo in 1841 to its termination in the 1920s.5 This article briefly explores how early Latter-day Saints approached the question of what constitutes valid baptism and then documents and analyzes the three other modes of rebaptism in the Church. Evident from this analysis is that rebaptism was prominent within the development of Latter-day Saint covenant theology and its resulting distinctions from other Christian traditions.

Valid Baptism

The Book of Mormon includes many accounts of baptism of the penitent by immersion before the coming of Jesus Christ at the volume’s apex. When the narration brings the reader to that moment, Jesus bestows authority upon his New World disciples to baptize by immersion and gives them a prayer to use in doing so (3 Ne. 11:21–27). In 1829, Oliver Cowdery gathered ecclesiastical and liturgical instructions from the Book of Mormon and created a document to govern the small band of believers in New York—the “Articles of the Church of Christ.” God had directed Cowdery to write, and the words were, in his words, “unto me as a burning fire shut up in my bones.”6 Upon formation of the Church of Christ the following year, Joseph Smith produced “Articles and Covenants” for the Church. This document included material from Cowdery’s “Articles” and appended to it several statements of belief, thus earning it the title of the “Mormon Creed” from antagonistic observers. Smith’s Articles and Covenants declared that the humble believers who desire baptism, and who witness to the Church that they are penitent and “willing to take upon them the name of Christ, having a determination to serve him unto the end, and truly manifest by their works that they have received the gift of Christ unto the remission of their sins” should indeed be “received unto baptism into the church of Christ.”7

Aside from affirming the inspiration of the Book of Mormon’s origins, the material in these Articles and Covenants was not particularly controversial within the Protestant culture of nineteenth-century America. One of the statements of belief even paralleled the Apostle’s Creed, and the ecclesiology of the Church was not particularly distinctive when compared with American contemporaries. However, not long after the document’s creation, and perhaps in response to the questions of believers, Joseph Smith approached God to clarify the rules of the Church in regard to baptism. And as he uttered the word of the Lord to his nascent Church, he ruptured not only the American religious landscape but also the topology of Western Christianity.8

For the better part of fourteen hundred years, Christians in the Western tradition had accepted “valid” baptisms, regardless of which church, if any, the baptizer belonged to.9 Then valid baptism became a prominent and contested issue during the Reformation with the rise of Anabaptists, or “credobaptists.”10 These people believed that only the baptism of a person who was accountable and capable of faith in Jesus Christ (believer’s baptism) was valid, and polemicists readily controverted those with opposing views of what constituted valid baptism. But whether churches held infant baptism or adult believer’s baptism by immersion as valid, they still accepted all valid baptisms (in their view) performed outside of their particular denominations. Thus, Methodists accepted the baptisms of Catholic converts, and Campbellites accepted the baptisms of Separate Baptists.11 The rise of credobaptists was so wildly controversial precisely because believer’s baptism repudiated the validity of countless baptisms throughout Christian history. “Rebaptism” of anyone was thus offensive to pedobaptists (believers in infant baptism).12 But credobaptists made the exact same argument, with shifted definitions for valid baptism, declaring that “re-baptizing believers is making void the law of Christ.”13 As the Westminster Confession summarized, “The Sacrament of Baptisme is but once to be administred unto any person.”14

On April 16, 1830, Joseph Smith dictated a revelation declaring that all Christian baptisms—what many Protestants viewed as the sign of God’s covenant with the elect—were like the law of Moses, representative of an “old covenant” and “dead works.” It is unclear whether this revelation took Protestant covenant theology seriously or turned it on itself, but the text had to have stung anyone who viewed his or her baptism as a sign or seal of God’s covenant.15 The revelation placed all Christians in the same space they had put Jewish people, and the voice of God declared “a new and everlasting covenant” and that “this church” was “built up unto me.” This last covenant described in the revelation was accessible only by the “straight gait” of a new baptism.16 Joseph Smith announced that the only valid baptism on the planet was necessarily performed by priests or elders ordained under his hand.17 This revelation situated the Church of Christ closer to Eastern Orthodoxy, which had long rejected “heretical baptism,” than to its immediate neighbors. Soon Smith alienated even this proximity. Just as Christian believers had to be “rebaptized” to join Smith’s Church of Christ, the Church soon found occasion to rebaptize its own members—something essentially distinct in Christianity. Over the ensuing decades, some Church members would be baptized upward of a dozen times.

Rebaptism and Church Discipline

In August 1834, William McLellin traveled through Indiana, preaching, laying hands on the sick to heal them, and baptizing. The Church had been previously established in the area, and McLellin regularly met with members and interested observers alike. Eden Smith and his wife, Elizabeth, lived in the area. They had both once been Church members—Eden had served an evangelizing mission of his own—but they were no longer part of the Church. We don’t know whether the Smiths left the Church or were removed by Church discipline. Another couple, Catrin and Elisha Hill—both excommunicants—also lived in the area. Over a period of three weeks, in response to McLellin’s preaching, all four “manifested their willingness to take upon them the name of the Lord” and “wished to return.” McLellin led them, along with others who wanted to join the Church for the first time, down to the river, where he baptized them by immersion. After the baptisms, McLellin wrote that “we then united in prayr and while brother Levi was praying I laid my hands on and confirmed those who had been baptized—We then partook of the ‘supper.’”18

Many churches in Antebellum America enforced discipline on their members, some more strictly than others. Church leaders across denominations regularly doled out judgments upon their members for infractions spanning a wide array of moral and social offenses, with the ultimate threat of excommunication being a possibility in the most serious cases. Though it took a few years for Joseph Smith to reveal the ecclesiastical structures to formally adjudicate and enforce Church discipline, Latter-day Saints regularly used terms like “cut off,” “excluded from fellowship,” and “excommunicated” to describe the status of those removed from Church membership.19 For the early Latter-day Saints, however, the prospect of excommunication was not merely a separation from the worship and association of other members. For the early Saints, salvation was a social affair. They were trying to build the city of Zion—a land of promise to possess “while the Earth shall stand” and “again in eternity no more to pass away.”20 Those who “apostatized” were stricken from the records of the Church, and as Joseph Smith wrote, they “shall find none inheritance” in the land of Zion.21 There was no salvation—spiritual or temporal—outside of the Church.22

Excommunication in Christian churches has generally indicated that the recipient is, as the term indicates, outside of communion, but there is no way to cancel valid baptism in traditional Christianity. Excommunication is a tool of church discipline wielded to encourage repentance and a return to fellowship. Excommunicants are typically barred from the Lord’s Supper and other aspects of church community and worship, but their baptisms are unaffected. There are no early Latter-day Saint records explaining a theology of excommunication, but just as converts from other churches had to be rebaptized in order to join the Saints or, as Hyrum Smith declared, come “into the visible kingdom of god” and “in to the visible Church of Christ,”23 so too were the penitent “apostate” Latter-day Saint required do the same in order to return.24

The two couples that McLellin baptized in Indiana are potentially reflective of two different practices of Church discipline. McLellin noted that the Hills were clearly “cut off” from the Church. Alternately, of the Smiths he only wrote that Elizabeth “had once been a member.”25 The Smiths may very well have left the Church of their own volition.26 While the Church required formal excommunicants to be rebaptized upon return to the Church, leaders also regularly required rebaptism for the disaffiliated or reprobate when no excommunication had taken place. Many people in the early Church, including prominent disaffected Church leaders, were rebaptized with no records of excommunication. For example, in 1843, Elisha Davis confessed his sins during a local conference in Freedom, Illinois, and asked to be rebaptized. Because he “acknowledge his sins without trial,” and because “the hand of fellowship had not been withdrawn from him,” his elder’s license remained in force.27 Moreover, with time, the frequent verdict of formal Church discipline was, if the subjects were penitent, a requirement of rebaptism without excommunication.28 For example, one missionary in 1855 who profaned the name of God was disciplined, rebaptized, and continued his service.29 In Southern Utah, when one particularly belligerent individual had made threats and assaulted some community members in 1866, the local bishop asked, “Shall we cut [him] off & throw him away?” After some discussion, the acting bishop’s counselor wrote the response: the man “should Make a Public acknowledgement & be rebaptized for the remission of sins & begin a New again; this was the feelings of all Presant.”30 Similarly, in 1891, several boys in Cardston, Alberta, who belonged to the Church stole pocketknives in a neighboring town. Their bishop subjected them to Church discipline. After he directed them to make restitution, they were all rebaptized.31

At other times, formal disciplinary meetings were not even held. For example, when one missionary in 1889 was pained with guilt over previously hidden sin, he wrote and confessed to Church President Wilford Woodruff, expecting to be relieved of his ministry. However, the Church President erred on the side of mercy, writing back and instructing him “to get rebaptized and have all my priesthood and former blessings resealed upon me, but not to be in a hurry in doing so; meantime to apply myself diligently in magnifying my calling as a missionary.”32

While Church leaders debated the relationship of excommunication to the other liturgies of the Church over the years,33 the requirement of rebaptism to rejoin the Church persisted from the earliest records to the present (though the terminology changed from excommunication to “withdrawal of membership” in 2020).34 The practice of rebaptizing people who weren’t formally excommunicated, however, was deprecated by Church leaders in the early twentieth century, which is discussed later in this article.

Rebaptism for “the Remission of Sins”

Late in his life, Brigham Young reminisced about his time as a missionary in England in 1840 and 1841: “In my traveling and preaching, many a time,” he said, he “stopped by beautiful streams of clear, pure water, and have said to myself, ‘How delightful it would be to me to go into this, to be baptized for the remission of my sins.’” In his retelling, when he arrived back in Nauvoo, Joseph Smith told him that “it was [his] privilege” to be rebaptized. He remembered that there was a “revelation, that the Saints could be baptized and re-baptized when they chose,” along with being baptized for their deceased friends and families.35 Joseph Smith committed very few revelations to writing in the Nauvoo era. His revelation of baptism for the dead, for example, came by way of sermons and a few instructional letters. There are no extant revelation texts on rebaptism or baptism for the dead. However, when Brigham Young did return to Nauvoo after crossing the Atlantic, he saw what one antagonist of the Church described as seeing “the river foam” with rebaptisms.36 Further, what contemporaneous records do describe is that by April 1841 many Church members, including Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon, were rebaptized “for the remission of their sins,” often before being baptized as proxy for their dead relatives and friends.37

The question of what religious work baptism performed in the cosmology of Christian believers is important and complicated. For centuries, Christians had debated the precise relationship between the remission of sins (also termed regeneration or rebirth) and the ritual of baptism. Catholics had long held that the sacrament of baptism itself effected regeneration. Many Protestants hesitated to ascribe that sort of power to a human act and instead viewed the Holy Spirit as the agent of regeneration, which could occur at any time. The remission of sins was, in fact, a necessary requirement for the admission to many Protestant churches.38 Although the Articles and Covenants of the Church appear to reflect a similar perspective, Joseph Smith regularly turned to the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and his own revelations, which necessitated a “baptism of repentance for the remission of sins” or the “remission of sins by way of baptism”—a position similar to that of the German Baptist Brethren and, more famously, Alexander Campbell.39 Latter-day Saints proselytized carrying the message that all humankind could be saved by the ordinances of “1st, Faith in the Lord Jesus Christ; 2d, Repentance; 3d, Baptism by immersion for the remission of sins; 4th, Laying on of hands for the gift of the Holy Ghost.”40 The injunction to rebaptize Christian converts, disciplined members, and “apostates” was a powerful antecedent of nontraditional approaches to baptism. While his precise logic isn’t clear in the documentary record, Joseph Smith concluded that all Church members could find a remission of sins through repeated baptisms.

On March 20, 1842, Joseph Smith delivered a Sunday sermon on baptism. As reported by Wilford Woodruff, Smith declared: “God hath decreed & ordained that man should repent of all his sins & Be Baptized for the remission of his sins.” At the end of his sermon, Smith “informed the congregation that he should attend to the ordinance of Baptism {in th}e . . . river near his house at 2 o-clock.” Woodruff witnessed the riverbank humming with people. Smith waded into the water and baptized “with his own hands about 80 persons for the remission of their sins.”41 At least one of these individuals was baptized for the first time—Emma Smith’s nephew Lorenzo Wasson. As Woodruff’s own experience shows, however, many of those baptized that day were certainly members in good standing. The following Sunday, Joseph Smith spoke again, this time on baptism for the dead. And again the Saints gathered as he went into the river and “Baptized all that Came unto him.” This time, however, Woodruff was not content to be a mere observer. He wrote: “I considered it my privilege to be Baptized for the remission of my sins for I had not been since I first Joined the Church in 1833.”42 Then, along with Apostle John Taylor, who was also rebaptized, Woodruff and the others walked to the temple and were reconfirmed.

While some like Woodruff and Taylor were rebaptized because of their personal desire for the experience, others appear to have had specific mandates for the ceremony. Just as some people were rebaptized before performing proxy baptisms, at least some people experienced rebaptism before participating in the newly revealed temple ceremonies. For example, before being sealed in marriage on August 27, 1842, Newell and Elizabeth Whitney were baptized “for remission of sins.”43 And once the temple font was completed, the Saints used it for “Baptizing for the dead, for the remision of Sins & for healing.”44 At the April 1842 conference, Joseph Smith clarified that “baptisms for the dead, and for the healing of the body must be in the font,” but “those coming into the Church, and those rebaptized may be baptized in the river.”45 Practically, however, the font remained a regular place for baptizing for the remission of sins, at least while it was open. The month after that conference, Wilford Woodruff noted that in one day at the font he had baptized “about 100 persons mostly for the dead.”46

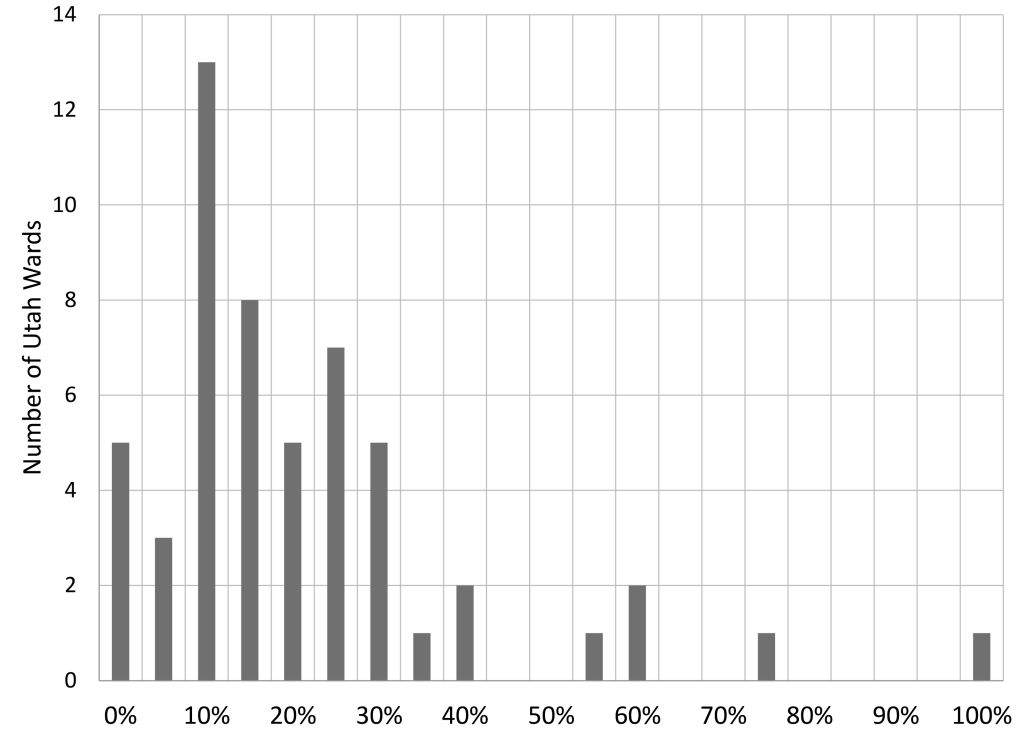

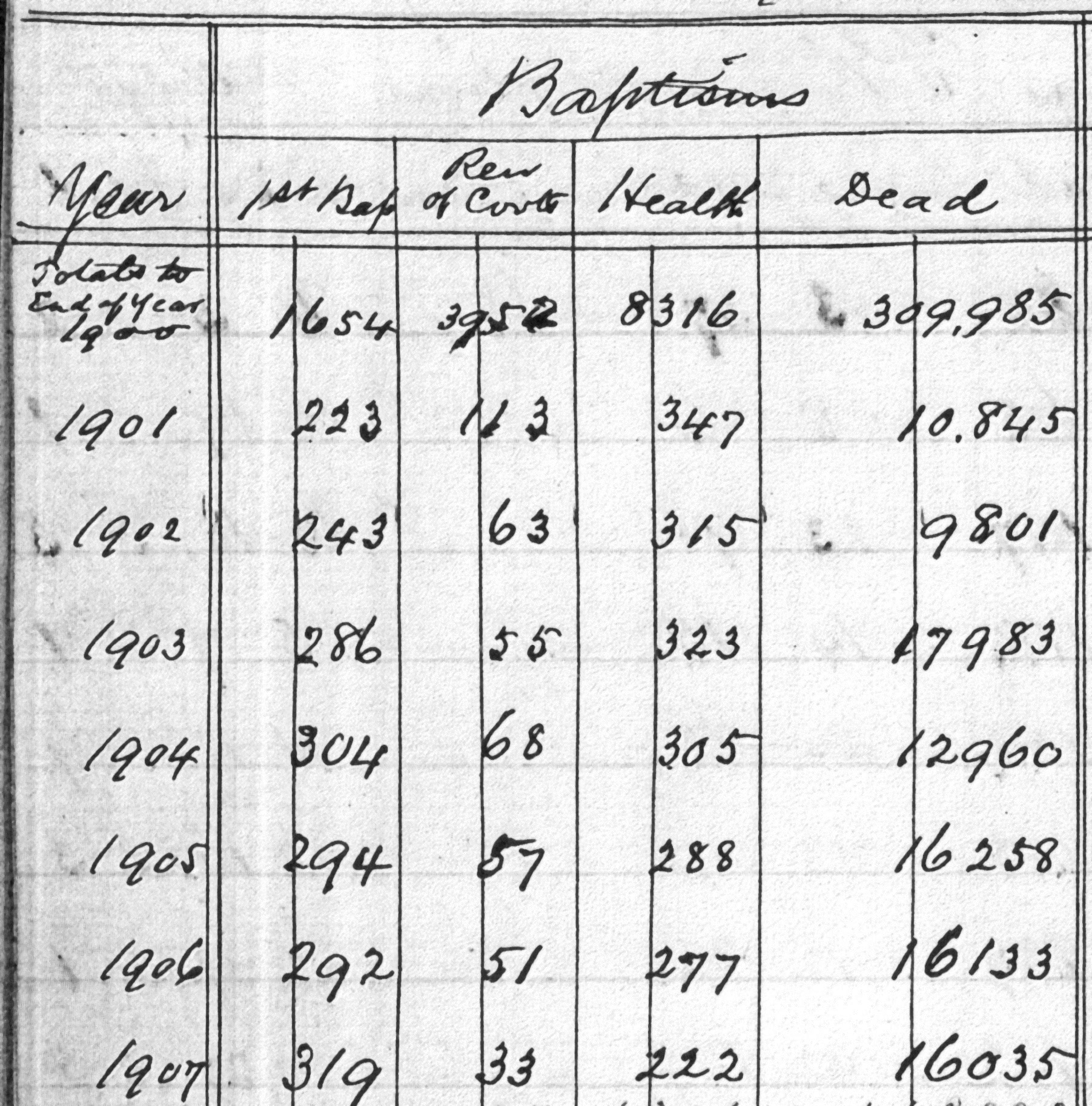

The Saints continued the practice of rebaptism for the remission of sins beyond the Nauvoo period. For example, in Winter Quarters, Wilford Woodruff sought rebaptism “for the remission of my sins” from Apostle Willard Richards. After being baptized, Woodruff then baptized Richards and several members of his household.47 Rebaptism of Church members continued along the trail west,48 into the Great Basin, and then throughout the world wherever the missionaries traveled.49 As discussed in the following section, eventually all immigrants who arrived in the Great Basin were rebaptized.50 Rebaptism was sufficiently common that in 1853, seventeen percent of all Church members in Utah had been rebaptized within the preceding twelve months, with one ward rebaptizing all its members (see fig. 1).51

Baptism for the Renewal of Covenants

A central message of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the twenty-first century is that the Church exists to help people “make and keep sacred covenants” on the path to exaltation. Church leaders introduced this phrase in 1985 as part of the “Young Women Values,” and it has since grown to occupy a place of primacy, being repeated in general handbooks, lesson manuals, general conference sermons, and even employment descriptions.52 When Latter-day Saints speak of covenants today, they largely mean the promises members make when participating in the liturgies of the Church.

In addition, Latter-day Saints have not only made the promissory covenants; they have also renewed them. In contemporary Church practice, the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper is the primary means by which Church members “renew” their covenants. However, in the nineteenth century, covenant renewal among Latter-day Saints was largely mediated by rebaptism, Brigham Young having introduced the practice upon entry into the Salt Lake Valley. However, before approaching this mode of baptism, it is important to understand how Latter-day Saints developed an understanding of covenants and their renewal that is distinct from other Christian traditions.

Covenants

Because covenants are featured prominently within the narratives of the Bible, scholars have long made them a focus of study. In the ancient Near East, covenants were the legal, religious, and ethical means to extend the “duties and privileges of kinship” to others, within various categories of relation and degrees of bilaterality. Individuals entered into covenants in liturgical ceremonies in which they made solemn oaths (or nonverbal oath-signs) and assented to the obligations of the specified relationship.53 Readers will likely be familiar with God’s grant-type covenants with Abraham and Israel and the language of redemption within Christian soteriology drawn from them.54 While Christians have also largely believed that Jesus Christ introduced a new covenant by which God saves humanity, precisely how they have related this covenant to those of the Hebrew Bible, and God’s salvific work more broadly, has varied. Early Latter-day Saints largely spoke, wrote, and published about covenants in ways that resonated with the Bible but contradicted many traditional Christian theologies. Joseph Smith revealed that Christ’s new covenant was everlasting and was the same covenant in force throughout human history.55

Joseph Smith also framed the covenant of Church membership as God’s renewed covenant with Israel. This is seen in the revelation on baptizing all Church members discussed at the opening of this article. Joining Israel in God’s covenant was adoptive—a transformation of the status of an individual to being part of the family of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.56 One did not make a new covenant with God; one joined the existing covenant.57 There were, however, other types of covenants. Essentially all Protestants focused on God’s salvific covenant, but Puritans, along with many Baptists and some Presbyterians, also created congregational articles of faith and church covenants that required church members, as one Scottish divine wrote, “to come under solemn, voluntary obligations unto the Lord” by promising to serve him and follow the rules outlined in the covenants.58 The direct analogy for Joseph Smith’s followers was their formal acceptance of the “Articles and Covenants”—a document that, like Protestant church covenants, laid out Church beliefs, structure, and membership obligations—after the organization of the Church of Christ in 1830.59 To reiterate, formally, Protestants did not use the term “covenant” to describe these membership promises, preferring words like “obligations,” “vows,” and “promises.” Instead, they reserved “covenant” to describe the relationship between God and his people and between the people of the Church.

Americans also regularly entered into legal covenants. Informed by ancient antecedents, within the western legal tradition, contracts had been relationship- or status-based agreements between parties, and covenants were a type of agreement formalized during land and property transactions (and in other contractual relationships as well).60 In fact, attorneys frequently used the paired synonyms, or legal doublet, “covenant and agree” in transactional documents. During the nineteenth century, legal scholars grew to view contracts and covenants as the legally enforceable promises of independent agents.61 Joseph Smith and other Latter-day Saints were clearly familiar with legal covenants. For example, Joseph Smith covenanted to fulfill certain obligations as part of a land transaction with his father-in-law in 1830.62 While Protestants were generally more theologically fastidious in how they used the term, both Methodists and Latter-day Saints occasionally used the language of covenant, drawn from both their religious and legal dealings, to mean a solemn promise, typically to God.63

There are scattered examples of Latter-day Saints using covenant language in places where traditionally words such as “promises,” “vows,” or “oaths” would typically have been used. In 1830, several Church elders witnessed that they “most solemnly covenant before God” to fulfill a mission to “the Lamanites.”64 In 1836, after a period of alienation between Joseph Smith and his brother William, they reconciled and “covenanted with each other in the Sight of God and the holy angels and the brethren, to strive from henceforward to build each other up in righteousness.”65 In these examples, Joseph Smith and other Church members used the secular contractual language of covenant to make a solemn religious promise. In some cases, Church members similarly made promissory covenants to obey God’s commandments, sometimes quite specifically. In 1833, Hyrum Smith stood at the shore of Lake Erie and preached to fifty men and women while referencing both the older and newer conceptions of covenant. He preached about the “knew [sic] covenant” that required industry, cleanliness, sacrament, and the ordination of elders. He then called upon his listeners to covenant to “keep the commandments of god & Be faithful.”66 In the Kirtland Camp—the group of approximately five hundred Saints that traveled from Kirtland to Far West in 1838—all members covenanted to “strictly to observe the laws of the camp and the commandments of the Lord.”67 And in 1843, in Freedom, Illinois, a Church elder covenanted at a local conference that he “would never be overcome again with liquor.”68

It was in Nauvoo that Joseph Smith redefined individual religious promises as covenants within the Church’s formal liturgy. Where others made vows, promises, and oaths, Joseph Smith asked Church members to make covenants. For example, instead of marital “vows,” Smith revealed a sealing ceremony that required participants to “covenant” to follow certain behaviors.69 Moreover, when Smith revealed the endowment ceremony, he used the method of teaching that he found in Freemasonry. And where the masonic presentation required initiates to make solemn promises in order to progress through the ritual, Latter-day Saints used the language of covenants in the temple endowment. Thus, during Joseph Smith’s lifetime, Church members used both the older and newer understandings of covenants. They looked to join Israel in God’s covenant, and they also participated in liturgies where they individually made solemn promissory covenants to keep specific commandments.

Renewal

As discussed above, Protestants viewed baptism as the sign (or seal) of God’s covenant, similar to how Israel saw circumcision as such.70 Puritan and Congregational church members brought their babies to the church to be baptized having God’s covenant sealed upon them. Later, as these children grew to be adults, they renewed (or reaffirmed) this covenant in ceremonies that allowed them access to the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. Covenant renewal grew to be a community-wide event, sometimes associated with fasting, and reaffirmed God’s bond to the individual and to the church.71 Puritans gathered together and made solemn promises in the “Presence of God, Angels and Men” to consecrate “our Talent; our Time our Estates, our Influence” to God, to avoid a litany of sins, and to follow specific expectations of righteousness.72 Though not universally held, some Puritans and Anglicans taught that the Lord’s Supper itself could be a means of covenant renewal.73 John Wesley, having been exposed to Anglican and Puritan covenantal theology, among other sources, readily turned to and ritualized covenant renewal for Methodists. They gathered—often annually at the beginning of the year, but also at camp meetings—to renew their covenants in ceremonies that usually concluded with the Lord’s Supper.74 This was a recapitulation of Israel’s covenant renewal in Exodus 19, Deuteronomy 29, and Nehemiah 9–10—a reaffirmation of and recommitment to God’s covenant. And whereas these ceremonies might include making specific promises or vows, such promises were part of the renewal process, not the covenants themselves.

Many Protestants also sought to renew some of their religious promises and vows. Following closer to the Roman tradition, the Church of England and, by extension, the Methodists maintained the practice of requiring baptismal vows—a series of four questions that in the 1824 Book of Common Prayer began with “Dost thou renounce the devil and all his works?” and ended with “Wilt thou then obediently keep God’s holy will and commandments, and walk in the same all the days of your life?”75 And while many Reformed traditions moved away from explicit vows toward catechesis, they nevertheless viewed baptismal vows as implicit to baptism.76 Anglicans could renew these vows, or promises, in certain services and through participation in the Lord’s Supper.77

The desire for renewal is a relatable impulse. Life is a persistent series of failures, large and small. This was true for Puritans, Methodists, and Latter-day Saints alike. However, when Church members talked about covenant renewal during Joseph Smith’s life, it was largely as a synonym for the Restoration, not as a personal recommitment to specific promises. For example, in 1837, a Church periodical discussed valid baptism throughout history, stating that no one had been authorized to perform it “till the renewal of the covenant and the restoration of the priesthood.”78

While Joseph Smith is not documented as teaching about personal covenant renewal, a few Church members did approach the idea. Writing from a small branch of believers in New Hampshire, Levi Wilder wrote to Kirtland in 1835, hoping to encourage proselytizing elders to visit his city and preach the gospel. He explained that “we have been in rather a cold state through the summer, but we have renewed our covenant, and find the Lord is ready and willing to bless us when we do our duty.”79

In the March 20, 1842, sermon that Joseph Smith delivered on baptism, discussed above, he appropriated Protestant language to describe baptism as “a sign ordained of God.”80 But instead of being a sign of God’s covenant, it was a sign “for the believer in Christ to take upon himself in order to enter into the Kingdom of God.” Protestants had described baptism as a sign of God’s covenant, while Joseph Smith largely framed baptism as the means God decreed to receive a remission of sins prerequisite to the reception of the Holy Ghost and to enter the Church. After Joseph Smith’s death, the way Church leaders discussed and taught about baptism shifted in two important ways. First, Church leaders opened the possibility of regularly renewing promissory Church covenants through rebaptism. Second and later, Latter-day Saints moved toward the idea of baptism being the method for the individual to make promissory covenants with God to serve him and keep his commandments in the first place.81

Rebaptism for the Renewal of Covenants

As mentioned above, Joseph Smith introduced the Nauvoo temple liturgy before his death. Before leaving Nauvoo, Church leaders spent day after day performing the endowment and sealing liturgies in the temple. They began to increasingly speak of “covenants” in the plural—meaning the promises Church members make to God and each other through Church liturgy. They also created opportunities to renew these covenants. As the Vanguard Pioneer Company wended its way west, Brigham Young became frustrated with the company’s “levity, dancing, checkers, cards, Swearing, &c.” He organized them into rows by priesthood office, and they each in turned manifested with uplifted hands that they would “serve the Lord, humble themselves, repent of their sins, cleave unto the Lord & renew their former Covenants.”82

The Vanguard company continued on to the Salt Lake Valley where they immediately set to work plowing, surveying, and making adobes. Two weeks after the first company members arrived, Brigham Young decided to dam up the small creek near camp and rebaptize first the Quorum of the Twelve and then the balance of the company. As Wilford Woodruff wrote, “We consider[e]d this A duty & privlege as we come into a glorious valley to locate & build a temple & build up Zion we felt like renewing our Convenant before the Lord and each other.” They baptized for three days, culminating on Sunday, August 8, 1847. Two hundred and eighty-eight were baptized in total, and Woodruff repeated, “We felt it our privilege to be baptized & to Baptize the Camp of Israel for the remission of our sins & to renew our covenants before the Lord.”83 From this point into the 1890s, Church policy was that every immigrant who arrived in Utah was to be similarly rebaptized.84 Some immigrants did question the practice and refused to be rebaptized. In response, Church leaders like Provo stake president James Snow reminded the Saints that rebaptism was revealed by Joseph Smith in Nauvoo and that those who were not rebaptized “are not consider [sic] in full fellowship.”85 And while rebaptism “for the remission of sins” remained common,86 the association between rebaptism and the renewal of covenants, what other Christians understood as renewing vows, grew inextricably from this point forward.

As with Brigham Young’s intercession in the Vanguard Company’s camp culture, the earliest and most prominent accounts of rebaptism for the renewal of covenants occurred during periods of revival and reformation. For example, in the summer of 1854, Apostle Erastus Snow traveled from Salt Lake City to St. Louis, where he presided over the Saints and started a newspaper. He found the Saints in many of the local branches to be “in rather a Lukewarm state” and consequently “endeavoured to stir them up” and to “commence a reformation.” As a result of Snow’s labors, he wrote that “nearly all the Saints in this city have renewed their covenants in Baptism and many who have been long on the back ground have come forward with renewed Zeal.”87 From Church leaders’ perspective, it was not just the far-flung branches of the Church that needed reform, however. The most significant reformation in Church history was centered in Salt Lake City two years later.

The “Mormon Reformation” of 1856 and 1857 was a period of intense introspection and recommitment for the Church.88 Church leaders withdrew the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper during the winter89 and drew up a list of questions—a “catechism”—for all members to submit to, with inquiries ranging from personal morality to personal hygiene. Even bishops struggled to live up to the standards.90 Leaders like Jedediah Grant and Brigham Young preached with fervor and sometimes invoked violent imagery to persuade the Saints to reform. The start of the Reformation coincided with the dedication of the stone-lined font near the Endowment House at the beginning of October. The dedicatory prayer included supplications to “feel the power of God and have power to work a great Refermation [sic] among this people.” The font was dedicated “to Baptize the Living & the Living for the dead.” At the close of the dedicatory prayer, the First Presidency rebaptized each other and several members of the Quorum of the Twelve.91 Brigham Young described how, after general conference, which over ten thousand Saints attended, “many are going forward” to the font and “renewing their covenants before the Lord.”92 The Reformation expanded out from Utah93 to Idaho,94 San Bernadino,95 St. Louis,96 New York City,97 Britain,98 and even South Africa99 where nearly every practicing Church member was rebaptized for the renewal of his or her covenants.

In this reformation, ward members often prepared for and then participated together in mass baptisms. In American Fork, the ward gathered at the water’s edge, and “Prest John Young gave some good instructions on the nature of covenants.” Everyone then entered the water and were rebaptized.100 “Some may think it strange,” Provo stake president James Snow confessed to a leadership meeting after the October conference, “that we should be required to renew their Covenants & do their first works over again.” Snow then listed ways the Saints had fallen short—from lying and eating too much to speaking against the Lord’s anointed and not bathing. “We have the privilege of being thrown into the batch & being ground over before we are baked (i.e) We have the privilige of going into the waters of Baptism & doing our first works over again.”101

The prayers for these baptisms were, however, not the same as when they were first baptized. During the Reformation, Brigham Young authorized that the baptismal prayer be changed to explicitly indicate the purpose of the ceremony.102 The revised prayer began, “Having been commissioned by Jesus Christ, I baptise you for the renewal of your covenant and remission of your sins.”103 The use of altered baptismal prayers remained in practice long after the Reformation, and when asked about the propriety of it, Young responded simply that “when an Elder baptizes any one, it is proper for him to say what the object of the baptism is.”104 This was the case for first baptisms as well as rebaptisms,105 and altered baptismal prayers appear to have been used for the renewal of covenants until the 1890s, as discussed below. Specific prayers for baptism for health endured until Church leaders deprecated the practice in the 1920s. Rebaptism for the remission of sins and the renewal of covenants was a normative practice from the Reformation forward. Individuals, entire wards,106 newly called local leaders,107 and far-flung missionaries108 all sought covenant renewal in the waters of rebaptism. There were, however, two special cases where it was required beyond the newly immigrated: before attending temple ceremonies and before joining a United Order.

Rebaptism and the Temple

Once the Endowment House font was dedicated, it was used for baptisms for the dead, in which case records were kept. It was also regularly used for rebaptisms, though no records were kept for these baptisms, and some suggested that “a cold running stream” was preferable.109 Regardless of where the rebaptism was performed, as John Taylor reaffirmed after the death of Brigham Young, “no person will be eligible to receive” any temple ceremonies “except they have been rebaptized.”110 Before Taylor’s daughter Ida could be sealed in marriage to John M. Whitaker in 1886, they were both baptized by “Brother J. Leatham, who has charge of baptisms at the Tabernacle.” Whitaker remembered that “it was necessary to get rebaptized to prepare” for the temple, ensuring that they were as “pure and clean as possible.”111 These rebaptisms were to occur before patrons arrived at the temple, as Joseph F. Smith wrote to one stake president. When people arrived without being rebaptized, the work in the temple was disrupted and delayed as workers were “compelled to re-baptize” candidates on the spot. Rebaptisms, Smith instructed, were to be performed before the issuing of temple recommends.112 The Saints were rebaptized before being endowed and before being sealed in marriage.

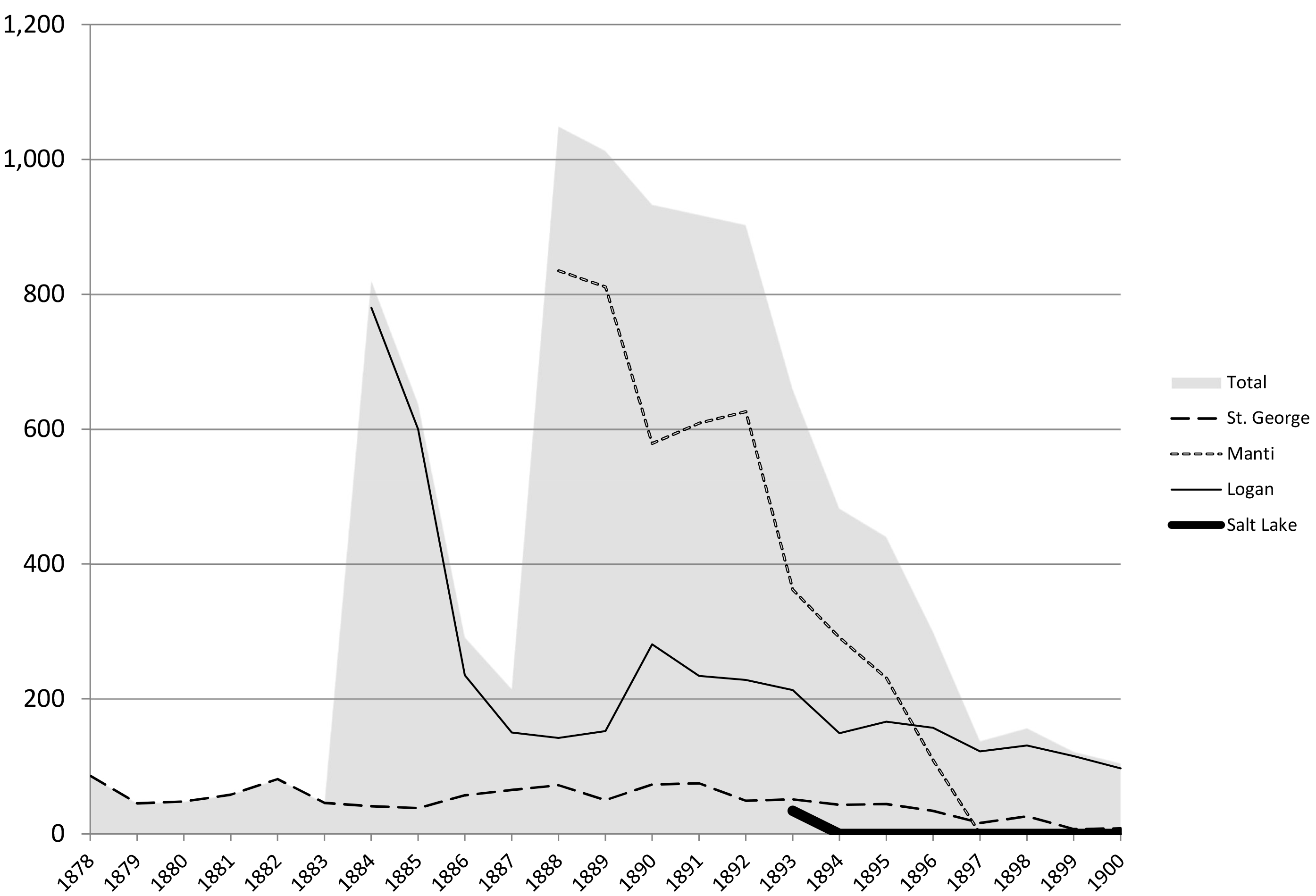

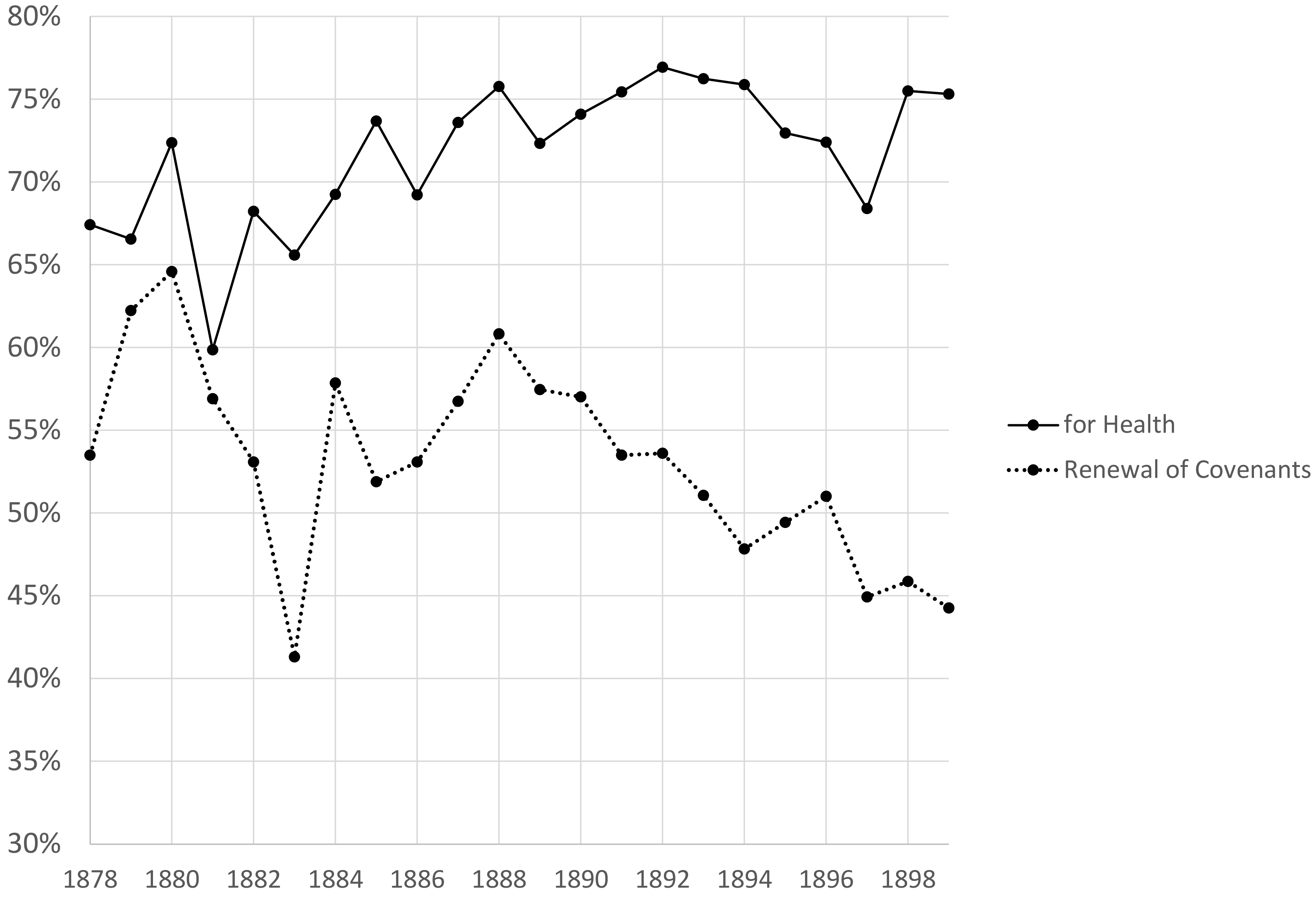

As the pioneer temples were constructed, their fonts were used for first baptisms, baptisms “for the renewal of covenants,” baptisms for health, and baptisms for the dead. While the first year of rebaptisms wasn’t recorded in the St. George Temple, subsequent records for all of the temples are available, and unlike the Endowment House, the temples kept records of living baptisms and rebaptisms. In the first years after opening each temple, people rushed to be rebaptized. And as the reports created by the Logan Temple recorder Samuel Roskelley show, rebaptisms were formally reported as being for the “renewal of covenants.”113 Because rebaptisms in Salt Lake City generally occurred at the Endowment House or Tabernacle fonts, rebaptisms for the renewal of covenants were uncommon in the Salt Lake Temple. In contrast, rebaptism for the renewal of covenants was common at all the other temples.

Rebaptism and the United Order

In the final years of his life, Brigham Young reintroduced the idea of the communitarian United Order to the Church—his “Order of Enoch.” Young required members to join United Orders, but in practice these organizations were never implemented. Members did create articles of associations for each ward, which included fourteen rules and prohibitions for members to follow spanning behaviors as varied as taking “the name of Deity in vain”; “refraining from adultery, whoredom, and lust”; and returning borrowed items to their proper owners.114 These rules were similar to the items in the catechism used during the Reformation. And like that earlier period of reform, the Saints were to be rebaptized, the prayer being altered for the occasion. Specifically, participants were to make “covenants by Baptism to observe the rules of the United Order.”115 Various versions of the prayer are documented, all with similar elements. For example, in Toquerville, Utah, one participant recorded it: “Having been commissioned of Jesus Christ, I baptized you for the remission of your sins; for the renewal of your covenants with God and your brethren, and for the observance of the rules that have been read in your hearing in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost; Amen.”116 In St. George, someone else recorded it: “for the Observance of the Rules of the Holy United Order.”117 And Apostle Brigham Young Jr. recorded: “and to observe the rules of [the] U[nited]. O[rder].”118 At least in some cases, the rules were read out loud before the baptisms.119 These baptisms were a primary emphasis. As one Richfield, Utah, resident wrote of a sacrament meeting in 1875, “members of the church should renew their covenants and be rebaptized was the main Text.”120 During the same period, the Cedar City, Utah, ward teachers canvassed their districts to gauge the preparedness of ward members to renew their covenants by rebaptism.121

As with the consecration efforts of the 1850s, the urban Saints who joined these orders never formally put the principles of the United Order into practice.122 Nevertheless, most Church members took their introspection seriously and realized spiritual blessings from reform. The women of the Salt Lake Nineteenth Ward held a regular prayer and testimony meeting during this period. People were understandably concerned that they might not be able to live up to the communitarian commitments. One member heard Brigham Young say that “he was in no hury for the people to be rebaptised but to think and consider and when we renew our covenants to keep them.” Penelope Goodrich remarked, “I hope I shall be willing to go into the Order when I am called,” saying that she was “willing to go into the waters of baptism and renew my covenants.”123 Others testified that “we shall have more blessings after being baptized.”124 The Salt Lake wards gathered at the Endowment House with hundreds being baptized at a time.125 A few months after the recommitment, one woman declared, “When I came home from being baptized I felt my sins were all forgiven me,” and another said, “Since I was baptized I have felt to rejoice, our afflictions are for our good.”126 A third described how “I have experienced many blessings since my rebaptism,” and a fourth celebrated how she was able to “draw nearer to God since I was rebaptized.”127

Reconsideration of Rebaptism

Bishop Frederick Kesler of the Salt Lake Thirteenth Ward kept a detailed diary, regularly documenting how rebaptism practice featured in the worship patterns of his community. He had lived through Nauvoo and the trek west, and in subsequent decades he rebaptized new immigrants and those preparing to go to the temple. Nearly every Thursday fast meeting, he helped confirm rebaptized Church members. He baptized in City Creek and in the Endowment House font—family members and ward members. Rebaptism was an integral feature of Latter-day Saint life, with adult members often having been baptized at least a half dozen times, if not more (including first baptism, then baptisms at emigration, during the Reformation, before being endowed and sealed, and then at the instigation of the 1875 United Order). Kesler was himself rebaptized—the first person to be baptized in the Salt Lake Temple font.128 In the first three weeks of January 1894, Kesler sent his son Alonzo with the monthly company to be rebaptized and saw him ordained an elder by the elders quorum president, endowed in the Salt Lake Temple, and then ordained a seventy and set apart as a missionary.129 At this same time, Church leaders were reevaluating baptism practice, often in the same temple, in a process that ultimately ended most rebaptisms of Church members.

Baptismal Prayers

The first aspect of rebaptism critically evaluated by Church leaders was the prayer. As shown previously, Brigham Young directed that the baptismal prayer be altered to state the reason for the baptism. After Young passed away, John Taylor first led the Church as the President of the Quorum of the Twelve, and together the Quorum immediately sustained the use of rebaptismal prayers that incorporated “for the remission of your sins, and for the renewal of your covenants.”130 Nine years later, however, Taylor began to revise his position. In December 1886, now as President of the Church, he responded to a local Church leader in Idaho, explaining that “the ceremony of baptism given in the Doctrine and Covenants can be used in re-baptism as well as in the first baptism.”131 A month later, he wrote to fellow Apostle John Henry Smith even more explicitly: “The only form of baptism of which we know anything is given by the Lord in the Book of Covenants to his church.” The canonical prayer “should be used,” he added, for all rebaptisms.132

Taylor’s instructions were delivered while he was hiding as part of the “Underground”—a fugitive during the antipolygamy “Raid.” As a result, his directives were largely unknown, and there remained a wide diversity in baptismal practice. However, First Presidency member George Q. Cannon remembered the letters John Taylor had written on the topic when they were on the Underground.133 In April 1891, Cannon responded to questions in the Juvenile Instructor about the form of baptism, because “some of the Elders insert in the form ‘for the remission of your sins,’ others ‘for the renewal of your covenants.’” Cannon concluded that “it is always safe, however, for those who officiate in baptisms to confine themselves to the written word.”134 In September 1891, Cannon responded to similar questions in the Juvenile Instructor, again giving the same response.135

A few weeks later, the Salt Lake City stake president inquired of the First Presidency about the same topic. They all recognized that multiple prayers were in use and that they “might not be objectionable,” but that any deviation from the canonical prayers was to be at the discretion of the Church President.136 When a member of the Quorum of the Twelve brought up the topic during a meeting the following November, after “considerable discussion” the conclusion was to use the canonical prayer “except where the president of the Church directs otherwise.”137 However, the temple had always been a source of normative practice for the Saints, whether for healing or baptism,138 and on December 3, 1891, the First Presidency decided to write to the temple presidents before a “decisive conclusion” could be made.139 They wanted to know “the precise form[s]” of baptismal prayer used for all baptisms in the temple, in addition to who authorized them.140

The First Presidency learned that the written rebaptismal prayers in use at the temples included the words “for the remission of sins and for the renewal of their covenants.” They also learned that it was Brigham Young who had apparently formalized these prayers for use. President Woodruff advocated for using the canonical prayer, except for baptism for health, but he believed that a final decision should be made when a full Quorum of the Twelve was present.141 While it appears that a consensus was reached mid-year,142 the topic arose in several meetings of the First Presidency and Twelve over the subsequent years.143 A letter changing the prayers used in the temples was not drafted until May 7, 1896.144 This letter directed the use of the canonical prayers for all rebaptisms except those for health.145

The Deprecation of Rebaptism

In the 1890s, as Church leaders interrogated the various prayers used for baptism among the Saints, they also reconsidered the various baptismal practices themselves. At the beginning of 1892, George Q. Cannon responded in the Juvenile Instructor to a question about the propriety of rebaptizing someone “guilty of profanity.” In his response, Cannon noted that “there have been many occasions in the Church when the Prophet of God who held the keys has counseled the Saints to renew their covenants by baptism.” However, Cannon also turned to the Doctrine and Covenants, which he suggested taught about proper confessional practice. The observance of confession and reconciliation made it “not necessary for men and women who transgress to always be re-baptized.”146 Still, Cannon adhered to the standard practices of the Church. A few months after writing this article, several of his children prepared to go to the temple for their marriage sealings, and Cannon rebaptized them himself at the Tabernacle.147

In 1891, the First Presidency had asked James E. Talmage—geologist, theologian, and future president of the Deseret University—to deliver a series of “theological lectures” to clarify Church teachings and core beliefs. The lectures were popularly attended and reprinted in the Juvenile Instructor. Talmage worked with a committee of Church leaders, including Apostle Abraham H. Cannon, to revise the lectures into a book for publication by the Church. Talmage systematized Latter-day Saint beliefs and practices in important ways, and the product of this labor—The Articles of Faith—became an instant classic, widely read to the present. In fall 1893, Talmage brought a number of questions to the First Presidency that the committee was unable to answer. First, he proposed revising Joseph Smith’s Articles of Faith to conform to the then-current understandings of theological terms, a change agreed to by the First Presidency.148 Next he asked about the baptismal prayers, and he summarized the answer in his journal that “any additions to the revealed form, or any other departure therefrom is unauthorized, and to be deprecated.” Talmage then wrote that he asked about rebaptisms more generally and that “the authorities were unanimous in declaring that rebaptism is not recognized as a regularly constituted principle of the Church; and that the current practice of requiring rebaptism as a prerequisite for admission to the temples, etc. is unauthorized.” Additionally, Talmage noted that “to require baptism of those who come from foreign branches to Zion” was “at variance with the order of true government in the Church.” These were strong policy statements that were reflected in his publication six years later. However, for the time being, things were not as formalized as Talmage indicated. Abraham Cannon’s summary of the meeting noted simply that “it was also decided that frequent baptisms will not be allowed, and that this sacred ordinance is becoming too common.” Moreover, Talmage noted himself that “nothing should be put in the way of anyone renewing his covenants by rebaptism if he feels the necessity of so doing.”149

As mentioned above, several months after this meeting, Alonzo Kesler was rebaptized before going to the temple and serving a mission. It appears that it took some time to implement stricter rebaptism rules Churchwide. In a priesthood leaders’ meeting of the April 1895 general conference, Joseph F. Smith spoke, and as summarized by an attending stake president, he indicated that some people in the Church wanted to be baptized “for every little thing” and that this was improper. Smith exhorted that people should confess their sins. He also told the Church leaders present that immigrants and people going to the temple for the first time would no longer be rebaptized. Rebaptism was to be reserved for who have “sinned especially.”150 At the same time, George Q. Cannon published an editorial in the Juvenile Instructor which suggested that rebaptism be reserved to those who had spent a significant amount of time not practicing their faith and those who had sinned against the brothers and sisters in their ward in disruptive manners. He noted that “it is far better for the Latter-day Saints to live day by day, so as to not be under the necessity of renewing their covenants” by rebaptism. He explained that “if the Church observes the sacrament properly, sins are confessed and forgiveness is obtained before partaking of the bread and the contents of the cup.”151 This placed the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper in the position of reconciliation between the Saints and God, and between the Saints themselves.

Church practice is difficult to change without a public and concerted effort. In 1897, Apostle Mariner Merrill spoke at the Cache Stake conference about, among other items, rebaptism being too common. He exhorted the Saints who had sinned to “repent and seek forgiveness, and that is all that is necessary.”152 George Q. Cannon made a similar point in the following general conference: “The First Presidency and the Twelve have felt that so much re-baptism ought to be stopped.” Church members must, if they commit sin, “repent of the sin, confess it, and make the confession as broad as the knowledge of the sin.”153 By the end of the century, the Church had published James Talmage’s Articles of Faith, which clearly stated that “there is no ordinance of ‘re-baptism’ in the Church,” and that “repeated baptisms of the same person are not sanctioned in the Church.”154 Nevertheless, the Logan Temple continued to rebaptize for the renewal of covenants for another decade. Church President Lorenzo Snow required rebaptism for the renewal of covenants of those who had participated in the temple liturgy, ceased to participate in the Church, and then returned before they were authorized to wear the temple garment.155 Church President Joseph F. Smith maintained this practice and also established a policy that those who were guilty of sexual sin but were penitent should not be excommunicated but should be privately rebaptized “for the renewal of covenants,” with no record of the baptism kept.156 After his administration (1901–1918), rebaptisms appear to have been limited to penitent excommunicants.

Rebaptism’s trajectory of declension mirrors in some ways the decline of baptism for health.157 Both baptismal practices were rooted in Joseph Smith’s teachings and were a prominent feature of the lived experience of Church members during the nineteenth century. As Church leaders critically evaluated teachings and practices with a focus on rooting them in the canonical texts, both rebaptism and baptism for health became incongruous with the outlook of Church leaders. However, whereas some forms of rebaptism are uncontroversially maintained within the tradition (in the case of former members), baptism for health has not been practiced at all since the Grant administration.

Conclusion

Patty Sessions, whose journal entry describing her rebaptism in Winter Quarters opened this article, joined the Church in 1834 when traveling missionary Daniel Bean immersed her in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Technically, this was also her first rebaptism, because she had been baptized a Methodist nearly twenty years earlier.158 In this way, she shares experiences with generations of Latter-day Saint converts to the present. Latter-day Saints are not alone in requiring the rebaptism of converts who have not had what they perceive to be valid baptism. However, Sessions was also a witness to rebaptism practices that are exceptional within the Christian tradition.

According to family tradition, her son-in-law had been excommunicated and rebaptized in Nauvoo.159 Besides her own rebaptism at Winter Quarters, she noted the rebaptisms of her daughter, granddaughter, and other family members over time.160 She wrote after being rebaptized again during the Reformation that “I never felt so weel [sic] in my life.”161 These sorts of distinctive Christian rebaptisms were a regular feature of her religious life, just as they were for all Latter-day Saints who lived at the time, regardless of where they lived. And though members of the Church in good standing are no longer rebaptized today, the practice played a central role in the development of the Latter-day Saint covenant theology that animates the contemporary Church.

In the nearly two hundred years since the early Restoration, some Christians have drifted from theological commitments that prohibit rebaptism. Today Christians of every denomination make pilgrimages to Israel and visit the Jordan River. There, many Evangelical Protestants enter the water to be rebaptized.162 Though Apostle George Smith traveled to Israel in 1873 with several other Church leaders and was rebaptized “where it is said John baptized the Savior,” today Latter-day Saints do not join them.163

Analyzing the patterns and purposes of rebaptism among Latter-day Saints helps historicize the most prominent beliefs and practices of the Church. Church members strive to follow the “covenant path” and seek to regularly renew their covenants.164 Rebaptism was the first liturgical method to renew covenants in the Church. This history helps us see that Latter-day Saints largely view covenants in terms of what other Christians see as promises and vows and helps distinguish important theological differences between traditions.

About the author(s)

Jonathan A. Stapley is a historian and scientist. He is the author of the award-winning The Power of Godliness: Mormon Liturgy and Cosmology (Oxford, 2018).

David W. Grua is a historian in the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He co-edited multiple volumes in the Documents Series and serves as the lead historian of the online Legal Series of the Joseph Smith Papers. He holds a PhD in American history from Texas Christian University, as well as history degrees from Brigham Young University. David is the author of the award-winning Surviving Wounded Knee: The Lakotas and the Politics of Memory (Oxford, 2016).

Notes

1. Donna Toland Smart, Mormon Midwife: The 1846–1888 Diaries of Patty Bartlett Sessions, Life Writings of Frontier Women, vol. 2 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1997), 102–3.

2. Charles M. Hatch and Todd M. Compton, eds., A Widow’s Tale: The 1884–1896 Diary of Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, Life Writings of Frontier Women, vol. 6 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2003), 537 (March 30, 1893). Whitney noted that there were also two baby blessings.

3. Orson F. Whitney, Diary (August 1, 1877, to September 6, 1877), COLL MSS 188, box 6, fd. 19, Merrill-Cazier Library, Utah State University, Logan, Utah.

4. D. Michael Quinn first documented these forms of baptism in his “The Practice of Rebaptism at Nauvoo,” BYU Studies 18, no. 2 (April 1978): 226–32. In contrast to Quinn, we have not found any evidence for rebaptism for the renewal of covenants until after the Nauvoo period.

5. Jonathan A. Stapley and Kristine L. Wright, “‘They Shall Be Made Whole’: A History of Baptism for Health,” Journal of Mormon History 34, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 69–112.

6. “Appendix 3: ‘Articles of the Church of Christ,’ June 1829,” [3], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 7, 2022.

7. “Articles and Covenants, circa April 1830 [D&C 20],” [4], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 7, 2022.

8. Ryan Tobler, “‘Saviors on Mount Zion’: Mormon Sacramentalism, Mortality, and the Baptism for the Dead,” Journal of Mormon History 39, no. 4 (Fall 2013): 207–10.

9. For the history of this practice, see Lynn Mills and Nicholas J. Moore, “One Baptism Once: The Origins of the Unrepeatability of Christian Baptism,” Early Christianity 11, no. 2 (2020): 206–26.

10. Bryan D. Spinks, Reformation and Modern Rituals and Theologies of Baptism: From Luther to Contemporary Practices (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 83–100.

11. Early on, John Wesley argued that valid baptism necessarily was performed by the episcopally ordained. He grew to accept lay baptism, and Methodists more broadly followed. Karen B. Westerfield Tucker, American Methodist Worship (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 84–85, 93–94. See also E. Brooks Holifield, The Covenant Sealed: The Development of Puritan Sacramental Theology in Old and New England, 1570–1720 (1974; Eugene, Ore.: Wipf and Stock, 2002), 66–69.

12. For excellent context and analysis of this debate as it played out between Methodists, Baptists, and Latter-day Saints, see Christopher C. Jones, “Mormonism in the Methodist Marketplace: James Covel and the Historical Background of Doctrine and Covenants 39–40,” BYU Studies Quarterly 51, no. 1 (2012): 86–90. It should also be noted that lay believers did sometimes seek out rebaptism despite institutional rejections. Baptists sometimes had their babies baptized, hoping that they would be baptized again as adults, and sometimes people baptized as infants sought baptism as adults. Jones, “Mormonism in the Methodist Marketplace,” 86–90; Janet Moore Lindman, Bodies of Belief: Baptist Community in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 117; William Pitts, The Gospel Witness (Catskill, N.Y.: Junius S. Lewis, 1818), 83, microfiche, 080 Sh64a 45343, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah (hereafter cited as HBLL).

13. Thomas Campbell, “The Mormon Challenge,” Painesville Telegraph (February 15, 1831), [2]. There are, of course exceptions to this broad consensus. English Separatist John Smyth rejected the sacraments of the Anglican church and was rebaptized. Holifield, Covenant Sealed, 66. In 1848, the German Baptist Brethren in the U.S. reaffirmed, in response to questions about accepting credobaptist converts into the church, that “it would be better to admit no person into the church, without first being baptized by the brethren.” Minutes of the Annual Meetings of the Brethren (n.p.: n.p., 1886), 124; Carl F. Bowman, Brethren Society: The Cultural Transformation of a “Peculiar People” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 212–17.

14. The Humble Advice of the Assembly of Divines, Now by Authority of Parliament Sitting at Westminster, Concerning a Confession of Faith: With the Quotations and Texts of Scriptures Annexed (London: Evan Tyler, 1647), 49.

15. For examples of such views, see Holifield, Covenant Sealed, 14, 26, 51, 76–77, 89, 96–98, 142–45, 151, 172–73. On Protestant covenant theology more broadly, see Guy Prentiss Waters, J. Nicholas Reid, and John R. Muether, eds., Covenant Theology: Biblical, Theological, and Historical Perspectives (Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway, 2020).

16. “Revelation, 16 April 1830 [D&C 22],” [4], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022.

17. Eleven years later, Joseph Smith recognized “sectarian” objections to Latter-day Saints not accepting other Christians’ baptisms, saying that it would be like putting old wine in new bottles. “Minutes of a Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Held in Nauvoo, Ill., Commencing Oct. 1, 1841,” Times and Seasons (October 15, 1841), 578. On ordination, see “Revelation, 9 December 1830 [D&C 36],” 48–49, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022.

18. Jan Shipps and John W. Welch, eds., The Journals of William E. McLellin, 1831–1836 (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies; Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 133, 135–36.

19. For an example document that includes all three terms, see “Letter to Wilford Woodruff, circa 18 June 1838,” [4], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022. Occasionally members were also “excludid from the church.” George Burket, journal, September 28, 1835, MS 10340, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City (hereafter cited as CHL). On Latter-day Saint discipline and context, see Nathan B. Oman, “Preaching to the Court House and Judging in the Temple,” BYU Law Review 2009, no. 1 (2009): 157–224.

20. Joseph Smith, in “Revelation, 2 January 1831 [D&C 38],” [51], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022. (Note as well the changes introduced in the 1833 printing.) See also “Revelation, 30 August 1831 [D&C 63],” Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022.

21. “Letter to William W. Phelps, 27 November 1832,” 3, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022.

22. Jonathan A. Stapley, Power of Godliness: Mormon Liturgy and Cosmology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 60–61. This exclusivity was tempered by developing Latter-day Saint universalism.

23. Hyrum Smith, Diary, November 29, 1832, and January 20, 1833, MSS 774, series 1, box 1, fd. 4–6, Special Collections Miscellaneous, Digital Collections, HBLL. On antecedent ideas of baptism and the visible church, see Holifield, Covenant Sealed, 42–43, 96–98.

24. See, for example, Vermillion Branch Conference Minutes, 1832 November to 1833 July, March 18, 1833, LR 5552 21, CHL; “Letter to J. G. Fosdick, 3 February 1834,” [23–24], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022; Orson Hyde, Ein Ruf aus der Wüste (Frankfurt: n.p. 1842), 75. Jonathan Green published an English translation of the latter: “Ein Ruf aus der Wüste 4.8: Orson Hyde on Confession and Disfellowship,” Times and Seasons (blog), March 28, 2021, https://www.timesandseasons.org/index.php/2021/03/einf-ruf-aus-der-wuste-4-8-orsond-hyde-on-confession-and-disfellowship.

25. Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 133, 136.

26. For example, on September 27, 1835, Edward Partridge rebaptized a penitent man “who had once belonged to the church, & had been an elder, but had withdrawn from the church.” Edward Partridge, Diary, September 27, 1835, MS 892, CHL.

27. Freedom [Illinois] Branch Conference Minutes, July 20, 1843, Historian’s Office Minutes and Reports (Local Units), 1840–1886, CR 100 589, CHL. These minutes also indicate that Davis was “restored to his former standing” during the reconfirmation.

28. See, for example, “Minutes, 30 January 1836,” [137], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022.

29. Salmon River Mission Journal, March 8 and 9, 1856, MS 4955, CHL.

30. Robert Glass Cleland and Juanita Brooks, eds., A Mormon Chronicle: The Diaries of John D. Lee, 1848–1876, 2 vols. (1955; Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983), 2:22. See also the case of two men who were tried by the ward for unruly conduct, with the verdict that they “repent of their sins be rebaptized forthwith and make a satisfactory confession to the brethren and sisters of the ward or be cut off from the church.” Tenth Ward General Minutes, 1849–1977, vol. 6, 1849–1866, October 28, 1853, LR 9051 11, CHL.

31. Donald G. Godfrey and Brigham Y. Card, eds., The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years 1886–1903 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1993), 180–81 (March 14, 1891).

32. William B. Smart, Mormonism’s Last Colonizer: The Life and Times of William H. Smart (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2008), 63, 67.

33. Stapley, Power of Godliness, 54–55.

34. General Handbook: Serving in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2020), 32.11.4; Larry D. Curtis, “After Changes to Handbook Terminology, LDS Church Members No Longer ‘Excommunicated,’” KUTV, February 19, 2020.

35. Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1855–86), 18:241 (June 23, 1874). No manuscript or shorthand version of this sermon is extant.

36. Oliver H. Olney, The Absurdities of Mormonism Portrayed (n.p., 1843), 8.

37. William Clayton, Diary, April 8 and May 9, 1841, MSS 47, Mormon Missionary Diaries, Digital Collections, HBLL; William Huntington, Journal, April 11 and 27, 1841 [p. 41], holograph, MSS 272, HBLL; Franklin D. Richards, Journals, typescript, April 11–May 2, 1841, holograph, MS 1215, CHL. Baptism for the dead records from this early period do note several cases of “first baptisms” and rebaptisms interspersed with the baptisms for the dead. See Nauvoo Baptisms for the Dead in the Mississippi River, 5, 11, 14, 38, 63, and 85, document 227681, FamilySearch Library, accessed September 9, 2022; Correspondence Baltimore Patriot, “Nauvoo,” New-York Spectator (August 23, 1843), 4.

38. Holifield, Covenant Sealed, 5; Westerfield Tucker, American Methodist Worship, 90–93, 105–6; David W. Bebbington, Baptists through the Centuries: A History of a Global People (Waco, Tex.: Baylor University Press, 2010), 188–89; Thomas L. Humphries Jr., “St. Augustine of Hippo,” in Christian Theologies of the Sacraments: A Comparative Introduction, ed. Justin S. Holcomb and David A. Johnson (New York: New York University Press, 2017), 49–50.

39. Luke 3:3; Acts 2:38; Moroni 8:11; “Revelation, circa Summer 1829 [D&C 19],” 42, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022; “Revelation, 7 May 1831 [D&C 49],” 82, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022; “Revelation, 14 June 1831 [D&C 55],” 91, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 9, 2022. On Baptists, see Minutes of the Annual Meetings of the Brethren, 56–57, 123, 207, 219, 226; E. Brooks Holifield, Theology in America: Christian Thought from the Age of the Puritans to the Civil War (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2003), 290, 299, 303–4. Some contemporaneous observers suggested that Smith was borrowing this emphasis from the Campbellites. “Candor,” letter to the editors, Christian Advocate and Journal, March 6, 1840, 115. For antecedent debates, see Holifield, Covenant Sealed, 80. It appears that the Reformed Methodists may also have advocated for baptism for the remission of sins. Pitts, Gospel Witness, 74. The remission of sins was included in prayers during the early Methodist baptism liturgy, but they were later removed. Westerfield Tucker, American Methodist Worship, 87, 92, 106.

40. “Church History,” Times and Seasons (March 1, 1842), 709. Smith frequently preached on faith, repentance, baptism for the remission of sins, and the Holy Ghost in Nauvoo.

41. Wilford Woodruff, The Wilford Woodruff Journals, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Benchmark Books, 2020), 1:499 (March 20, 1842), braces in original.

42. Woodruff, Journals, 1:500 (March 27, 1842).

43. “Revelation, 27 July 1842, in Unidentified Handwriting–A,” [2], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 15, 2022.

44. Woodruff, Journals, 1:483 (November 21, 1841).

45. “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 12 (April 15, 1842): 763.

46. Woodruff, Journals, 1:506 (May 15, 1842).

47. Woodruff, Journals, 2:133 (August 8, 1846).

48. For example, Bathsheba W. Bigler Smith, Diary, June 29 and September 2, 1849, MS 36, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City; John Oakley, Journal, June 19, 1856, microfilm of holograph, MS 1996, CHL.

49. At least some early missionaries were rebaptized before being blessed and set apart, while others were rebaptized when they arrived in their service areas. Juanita Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844–1861, vol. 2 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1964), 454 (October 16, 1852); Las Vegas Mission Record Book, June 3, 1855, LR 5691 21, CHL; Salmon River Mission Journal, July 8, 1855, and May 18, 1856. For examples of rebaptism for the remission of sins in the Pacific Islands, see George Q. Cannon, Journal, April 19, 1851, and May 28, 1852, The Journal of George Q. Cannon, Church Historian’s Press, accessed September 7, 2022; S. George Ellsworth, ed., The History of Louisa Barnes Pratt: Mormon Missionary Widow and Pioneer, Life Writings of Frontier Women, vol. 3 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1998), 144; Edward Leo Lyman, Susan Ward Payne and S. George Ellsworth, eds., No Place to Call Home: The 1807–1857 Life Writings of Caroline Barnes Crosby, Chronicler of Outlying Mormon Communities, Life Writings of Frontier Women, vol. 7 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2005), 134. For examples in Britain after 1847, see Cheltenham Conference Historical Record, 1850–1855, 9, 12, 15, 19, 22, holograph, LR 1631 21, CHL; Glasgow Conference General Minutes, 1840–1856, 1840–1846, pp. 175–81, holograph, LR 3194 11, CHL.

50. Many of the rebaptisms in the first decades in the Great Basin are documented in “Historian’s Office Rebaptism Records, 1848–1876,” holograph, CR 100 591, CHL.

51. Data drawn from “Report of the Bishops,” Deseret News, October 15, 1853, 179. Note that this report does not distinguish between modes of rebaptism.

52. “Young Women Values,” Young Women Special Issue [New Era] (November 1985): 27. See also Janice Kapp Perry, “I Walk in Faith,” Young Women Special Issue [New Era] (November 1985): 14–15. For more information on the development of these values and the Young Women’s program introduced in 1985, see the forthcoming history of Young Women to be published by the Church Historian’s Press in 2024.

53. See Scott W. Hahn, Kinship by Covenant: A Canonical Approach to a Fulfillment of God’s Saving Promises (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), 1–33.

54. See T. Benjamin Spackman, “The Israelite Roots of Atonement Terminology,” BYU Studies Quarterly 55, no. 1 (2016): 39–64.

55. See Terryl L. Givens, Feeding the Flock: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Church and Praxis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 14–44; Nathan B. Oman and Jonathan A. Stapley, “Covenant without Contract,” book chapter forthcoming. Note that Givens perhaps simplifies Reformed covenant theology, which views God’s covenant of grace in place throughout human history. See Waters, Reid, and Muether, Covenant Theology.

56. Samuel M. Brown, “Early Mormon Adoption Theology and the Mechanics of Salvation,” Journal of Mormon History 37, no. 3 (Summer 2011): 3–52.

57. See, for example, A Collection of Sacred Hymns, for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in Europe (Manchester: W. R. Thomas, 1840), nos. 160, 162, 166.

58. Archibald Mason, Observation of the Public Covenants, betwixt God and the Church: A Discourse (Glasgow: E. Miller, 1799), 14. Note that some in these groups also militated against such covenants of duty. See also David A. Weir, Early New England: A Covenanted Society (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2005).

59. “Minutes, 9 June 1830,” 1, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 15, 2022.

60. P. Brady Leigh, An Abridgement of the Law of Nisi Prius, vol. 1 (Philadelphia: P. H. Nicklin and T. Johnson, 1838), 602; Sir John Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 5th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 339.

61. Oman and Stapley, “Covenant without Contract.”

62. “Agreement with Isaac Hale, 6 April 1829,” [1], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 15, 2022. See also “Lease to Willard Richards, 4 January 1842,” Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 27, 2022; “Lease to John Taylor and Wilford Woodruff, between 8 and 10 December 1842,” Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 27, 2022.

63. Henry Moore, The Life of Mrs. Mary Fletcher, Consort and Relict of the Rev. John Fletcher (New York: J. Kershaw, 1824), 119; William O. Booth, “Memoir of William Fishwick, Esq., of Long-Holme,” Wesleyan-Methodist Magazine (July 1842): 548; M. M. Henkle, The Life of Henry Bidleman Bascom, D.D., LL.D., Late Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (Louisville: Morton and Griswold, 1854), 53. In 1827, Methodist Henry Tarrant created and signed “in the presence of God” a written covenant that delineated his relationship to God, including several promises and commitments. W. Frith, “Memoir of the Later Rev. Henry Tarrant,” Wesleyan Methodist Magazine (October 1845): 418–20. Two examples that are illustrative of how legal terminology was appropriated for religious promises among Latter-day Saints are the deeds of consecration used in the early Zion period of Missouri and Wilford Woodruff’s written consecration of property before he left on a mission on the last day of 1834. The early deeds were legal agreements and covenants between individuals and Edward Partridge to transfer property. Levi Jackman, Deeds of Consecration and Stewardship, MS 3103, CHL. Woodruff’s document is a religious declaration that he did “freely covenant with my God that I freely consecrate and dedicate myself together with all my properties and affects unto the Lord.” Woodruff, Journals, 1:28 (December 31, 1834).

64. “Covenant of Oliver Cowdery and Others, 17 October 1830,” [1], Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 15, 2022.

65. They then repeated the covenant a few weeks later with the Quorum of the Twelve. “Journal, 1835–1836,” 96, 124, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 15, 2022. See also “Revelation, 26 April 1832 [D&C 82],” 129, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 15, 2022; “Covenant, 29 November 1834,” 87–89, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed September 15, 2022.

66. Hyrum Smith, Diary, April 1, 1833.

67. Kirtland Camp Constitution and Journal, 1838 March–October, July 8, 1838, holograph, MS 4952, CHL.

68. Freedom Branch Conference Minutes, July 20, 1843. See also Freedom Branch Conference Minutes, September 3 and 4, 1843, holograph, CHL.