The Book of Mormon Art Catalog

A New Digital Database and Research Tool

Article

Contents

You can learn much about a society from its religious art. Compare, for example, two images of Christ’s descent from the cross—one a Counter-Reformation Flemish painting and the other from just twenty years later in nearby Protestant Amsterdam. In the earlier piece, Peter Paul Rubens (fig. 1) creates a scene of movement, drama, vivid color, and swirling drapery and depicts the body of Christ as muscular and heroic. In the second, by Rembrandt (fig. 2), we see a somber, quiet, darkly monochromatic scene and Christ’s frail, sagging body. How might we account for such different visual interpretations of this pivotal biblical moment by two nearly contemporary artists? And what might these differences tell us about the religion, the people, and their values?

Rubens, working in Catholic Flanders and responding to the Reformation, created monumental, engaging art that sought to draw people back to the Catholic church. Christ’s body has the pallor of death yet is still heroic in its pose. Looking to ancient classical statues, Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo, and Italian Baroque innovators like Caravaggio, Rubens created a scene of dramatic courage.1 The placement of figures creates a strong pyramidal shape that draws the viewer’s eye upward.

Rembrandt’s painting employs many of the same elements, but in a rather different way. Here, everything appears to sink into a pool of dark despair in the lower part of the canvas. The figures each retreat into their own grief, as opposed to the unified heroism in Rubens’s grouping. The white body of Christ looks small and weak. Compared with Rubens, Rembrandt presented a scene that is less dramatic, more earth-bound, and more pitifully human. This is in part due to the impact of Reformation theology, with its emphasis on the miracle of God’s grace through faith, even in a fallen world.2

This quick comparison provides only the briefest interrogation of these paintings, but it gives an idea of the enormous influence religion and culture can have on artistic expression. Moreover, it indicates the power of art to shape a certain response in the viewer and to affect belief. Similarly, what might art based on the Book of Mormon tell us about the beliefs and cultures of those connected to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints? It has been difficult to get a clear view of how Latter-day Saints have been engaging artistically with the Book of Mormon because the sources were so widespread and many artworks were inaccessible to the public. This lack of access was problematic for not just scholars but also artists. In many cases, patterns established in the most-viewed Book of Mormon art influenced later artists. Meanwhile, alternative approaches or styles from outside our specific religious visual world are largely forgotten or unexplored. This trend influences not just artists but members of the Church too, who tend to turn to known, easily accessible artworks in their scripture study and teaching.

For centuries, religious leaders have understood art’s ability to bring religious text and doctrine to life in the viewer’s mind, as well as the unique emotional effect of visual art. Likewise, leaders of the Church have long encouraged members to be active in the arts. Even in the nineteenth century, the Church commissioned artists to illustrate Book of Mormon scenes,3 appointed artists to paint murals in temples,4 and called artists on missions to Europe specifically to further their art training.5 Somewhat more recently, in his “Gospel Vision of the Arts” message, President Spencer W. Kimball famously said, “We are proud of the artistic heritage that the Church has brought to us from its earliest beginnings, but the full story of [The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints] has never yet been written nor painted nor sculpted nor spoken. It remains for inspired hearts and talented fingers yet to reveal themselves.”6

Religious art has the potential to teach and inspire in powerful ways. However, to some degree, religious art is inherently problematic, since artists are often guessing at details, there may be multiple competing yet valid interpretations of a scripture passage, and visual art is simply a different medium than scriptural text and therefore communicates differently. Access to a broader variety of art helps address these issues because it creates more space for diverse interpretations and personal responses.

The Book of Mormon Art Catalog

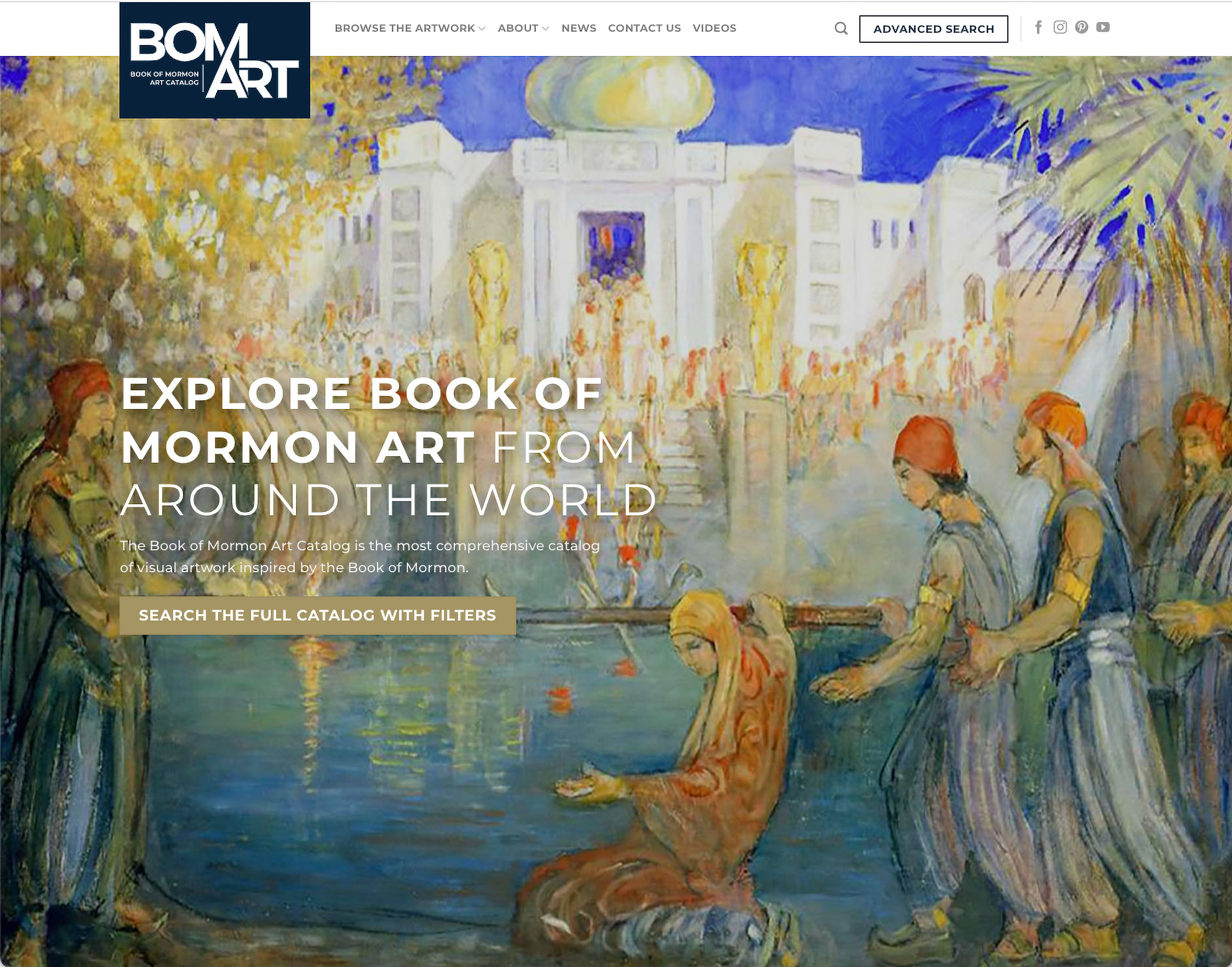

The Book of Mormon Art Catalog aims not only to recover the full history of art based on this book of scripture but also to inspire new and varied artistic production to further illuminate the scriptures and bring viewers closer to Christ (fig. 3).7 The catalog is a comprehensive, open-access, searchable, and growing digital database of more than three thousand images, providing unprecedented access to visual imagery inspired by the Book of Mormon. It brings together for the first time Book of Mormon art from a range of public and private collections, museums, galleries, studios, exhibitions, and publications. In this role, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog supports research and education, promotes greater knowledge of artists worldwide, highlights the diversity of Latter-day Saint art and artists, and provides a study and devotional resource for members of the Church and other interested individuals. The project is funded by a grant from the Laura F. Willes Center for Book of Mormon Studies, part of the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship at Brigham Young University.

In addition to familiar images, the catalog includes many artworks that are difficult to locate. Artist Kathleen Peterson, for example, allowed the inclusion of her Book of Mormon art series, which can’t be found anywhere else online. Peterson’s work often highlights the experience of women in the scriptures, making her series a welcome addition to the catalog. For instance, although there are numerous depictions of Helaman’s stripling warriors, Peterson’s depiction is one of only a handful to consider the role of their mothers.8 Her Mothers of the Stripling Warriors exudes a tender fortitude as a mother prepares to send her son into battle (fig. 4).9

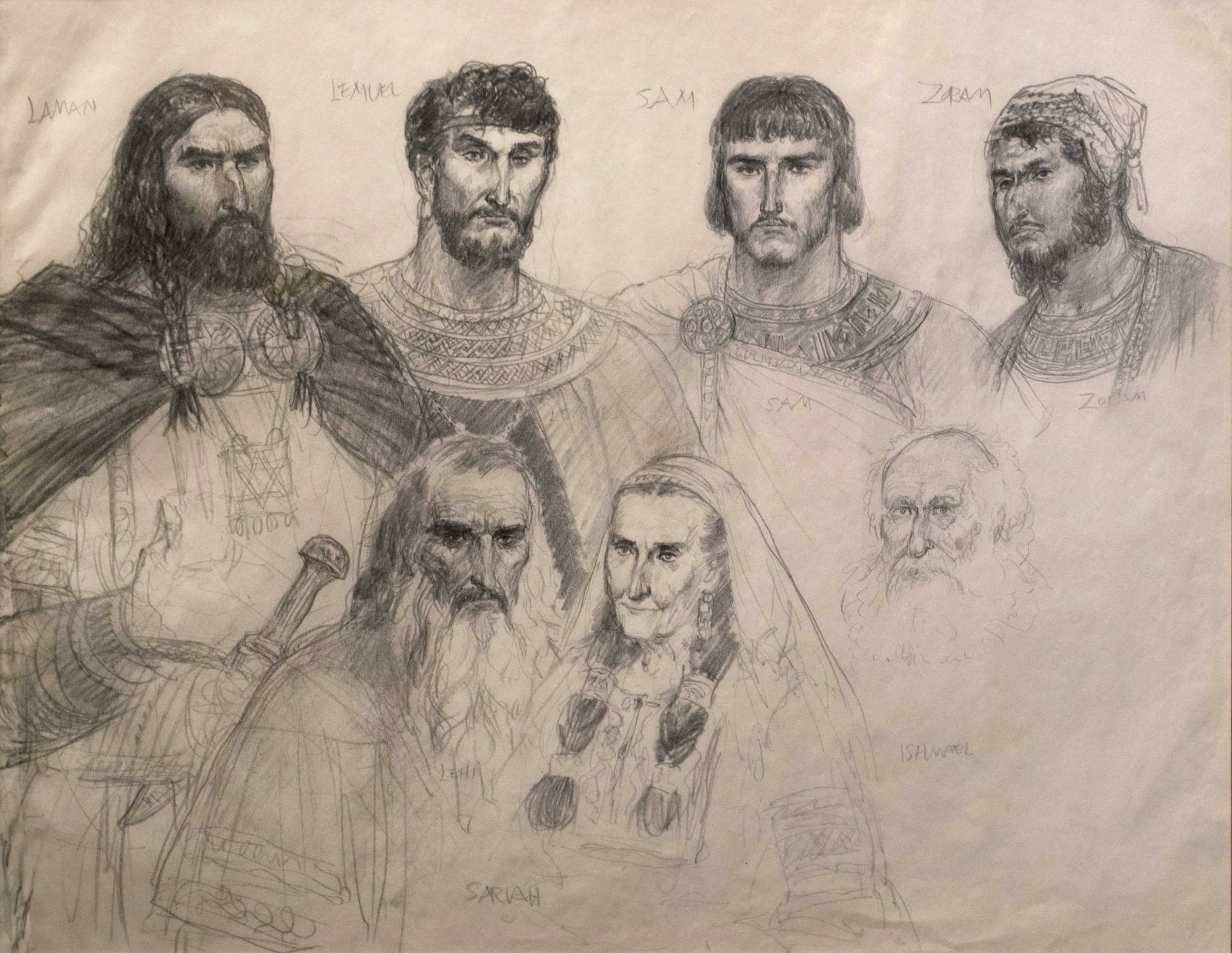

Private collections of art are also represented in the catalog. Anthony’s Fine Art and Antiques allowed us to include its vast collection of drawings by Arnold Friberg.10 Rarely seen publicly, these sketches give greater context for Friberg’s famous series of twelve paintings done in the 1950s. Friberg sketched a number of scenes and figures that were never realized as finished paintings, including a representation of Lehi’s dream and a group portrait of Nephi’s family (fig. 5).11

The collection of the Church History Museum of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints includes hundreds of Book of Mormon artworks, many of which have never been publicly documented before. The Book of Mormon Art Catalog team identified these artworks in the Church History Museum, requested permission from the Church to include them, and then worked to secure image files, giving the public access to many of these images for the first time.12 One example is a rug weaving by Diné artist Leta Keith depicting 1 Nephi 8 (fig. 6).13 Keith lived in Arizona on a Navajo reservation. She began weaving when only seven years old and continued to create rugs throughout her life, while serving for many years as the Relief Society president of the Chilchinbito Branch. In this weaving, Leta portrayed a traditional Navajo village combined with elements of Lehi’s dream, such as the tree of life and the great and spacious building.

Book of Mormon art can also be found in various Restoration branches, and this project brings them all together. For example, the Community of Christ owns one of the very earliest visual depictions of a Book of Mormon scene. It was painted by David Hyrum Smith, the youngest son of Joseph and Emma Smith. As the earliest known image of Lehi’s dream, it draws on the tradition of European history painting to depict Lehi and his heavenly guide in classical poses within the landscape (fig. 7).14

Research Possibilities

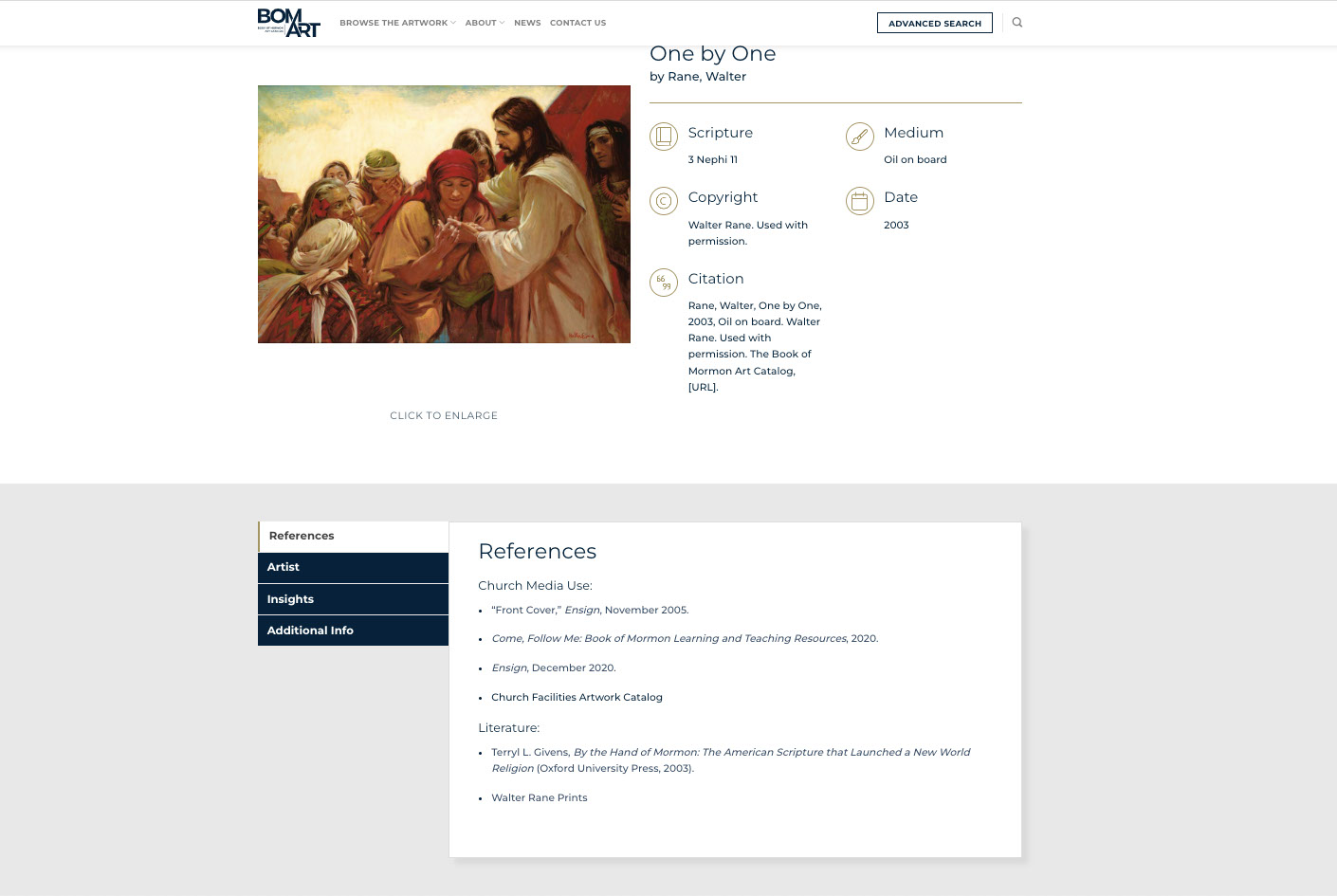

More than just a list of artworks, the Book of Mormon Art Catalog also includes extensive research. Each artwork entry includes primary information such as artist, title, date, medium, dimensions, copyright information, and scripture reference (fig. 8). Several tabs below the entry organize additional data about the artist, use of the image in Church media, references in publications, exhibition history, awards, style and technique, the inclusion of figures and symbols in the work, and the physical location of the piece. Each category utilizes a structured vocabulary for indexing to facilitate search retrieval. The site includes as much information as possible about copyright, location, links to the artists’ websites, and links to commercial galleries to protect the artists and to help users know where to secure image permissions for their own projects or where to purchase artworks or prints.

With this data now attached to the artwork, users can browse the site in two main ways. First, they can use six broad browsing categories organized into lists: artist, date, scripture reference, nationality of the artist, topic, and style and technique (fig. 9). Second, they can conduct specific, advanced, multivariable searches of the database (fig. 10). This powerful research tool makes possible a more thorough analysis and understanding of Book of Mormon art than has ever been available before. For instance, a scholar can compare how female and male artists have portrayed Nephi. Or an artist can review scenes of King Benjamin that are included in official Church media versus those that are not. Or a Sunday School teacher can find art about the Savior’s visit to America that was done by a South American artist.

To provide a sense of the types of analysis available through the Book of Mormon Art Catalog, this short study will briefly review two broad trends that have begun to emerge from the data. First, the production of Book of Mormon art has increased substantially over time, not as a steady growth but rather in fits and starts. And second, the bulk of Book of Mormon imagery concentrates on just a handful of topics or figures.

Production Patterns over Time

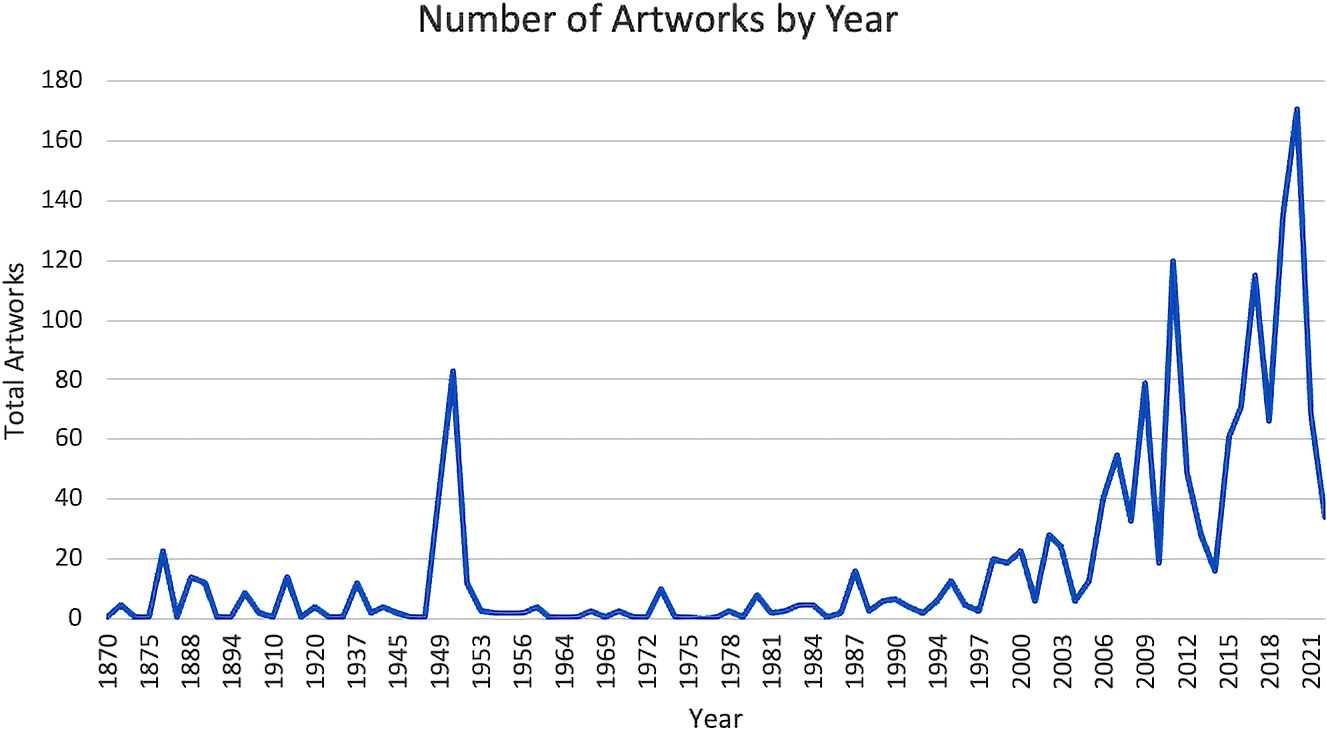

First, a consideration of production trends (chart 1). After a flurry of initial artistic activity in the late 1880s, resulting in seventy known images from 1870 to 1903, only forty-four known Book of Mormon images originated from 1904 to 1948.15 Activity picked up again in the early 1950s with the work of Minerva Teichert and Arnold Friberg, although they appear to be the only two artists working in earnest on the Book of Mormon during this time.16 The 1970s saw an increase in Book of Mormon images, as the Church was commissioning Book of Mormon art for its correlated manuals and materials. Much of this was in the style of straightforward, comic strip–style illustrations that appeared in the Church’s Book of Mormon Stories, first published in 1978.17 Then Book of Mormon artwork production doubled in the 1980s and almost doubled again in the 1990s, largely due to the interest of Church History Museum (formerly known as the Museum of Church History and Art) curators like Richard Oman in commissioning art on Lehi’s dream and soliciting art from a broader international pool of artists. After 2010, there was an explosion of Book of Mormon art. The upward trend appears to continue, with more than 270 Book of Mormon–inspired artworks produced in the three years from 2020 to 2022, which is a greater volume of art than was produced (or at least that we know of) in the first 120 years combined after the publication of the Book of Mormon.

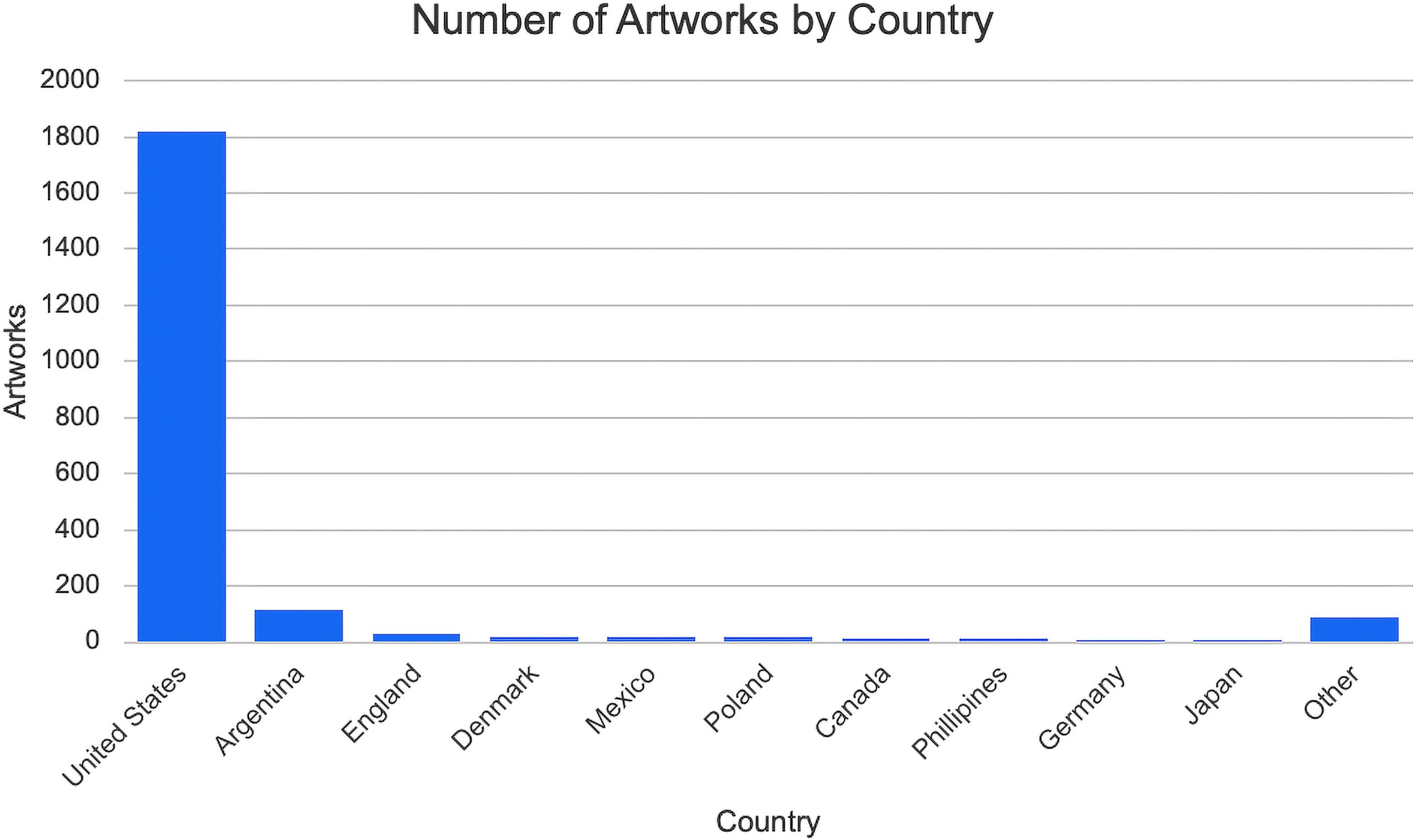

Artworks in the catalog originated from fifty-one different countries, but 85 percent of Book of Mormon art has been created by artists from the United States (chart 2). Except for nineteenth-century pieces made by pioneer immigrants from England and Denmark, Book of Mormon art from outside the United States is unknown until 1979, with two pieces from northern European countries produced that year. It was not until the later 1980s and 1990s that there began to be documented Book of Mormon art from Asian, Latin American, Middle Eastern, and African countries. This data confirms that competitions like the Church’s International Art Competition and Scripture Central’s annual art contest (formerly known as Book of Mormon Central), as well as recent initiatives at the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts, have done much to increase the production and visibility of artists and artworks outside of the United States. The data also demonstrates, however, that there is still room for growth for art originating internationally.

Concentration of Topics

One way to browse the Book of Mormon Art Catalog is with a list of one hundred topics that grew organically from the documented artworks. Yet not all topics have received the same attention in art. In fact, the sixteen most popular topics account for about half of all Book of Mormon imagery (chart 3). Lehi’s dream is far and away the most frequently depicted topic or scene from the Book of Mormon and is depicted almost twice as often as the next most popular topic, which is Christ in ancient America.

|

Topics |

Number of Artworks |

|

Lehi’s dream |

236 |

|

Jesus Christ in ancient America |

124 |

|

Abinadi and King Noah |

75 |

|

Stripling warriors |

69 |

|

Nephi and brothers |

55 |

|

Moroni (Captain) and title of liberty |

54 |

|

Brother of Jared |

54 |

|

Nephi obtains the plates |

52 |

|

Ammon and King Lamoni |

51 |

|

Nephi preaches |

49 |

|

Alma (son of Alma) preaches |

48 |

|

Liahona |

47 |

|

Nephi’s ship |

47 |

|

Jesus Christ blesses Nephite children |

46 |

|

Alma (father of Alma) baptizes |

45 |

|

Samuel the Lamanite |

44 |

|

Total |

1,096 |

|

All other topics |

1,115 |

Chart 3. The sixteen most frequently depicted topics account for almost half of all Book of Mormon art. Lehi’s dream is the most popular topic to be visualized in art.

More study is needed to understand why these are the most frequently depicted scenes. Could it be that they are scenes that best lend themselves to narrative art? Is it important that many of them were among the earliest to be illustrated? Some scenes, such as Lehi’s dream, Nephi preaching, Nephi’s ship, Nephi with his brothers, and the Liahona appear earliest in the Book of Mormon, so perhaps that has an effect. It would be interesting to examine which of these topics have been discussed the most by Church leaders. It is also worth noting that all of these most popular scenes are focused on male figures. Many depictions of women from the Book of Mormon did not appear until recently. The first image of Abish, for example, appeared in the year 2000. And except for a 1950 sketch by Arnold Friberg, the wife of King Lamoni was not visualized until 2003.

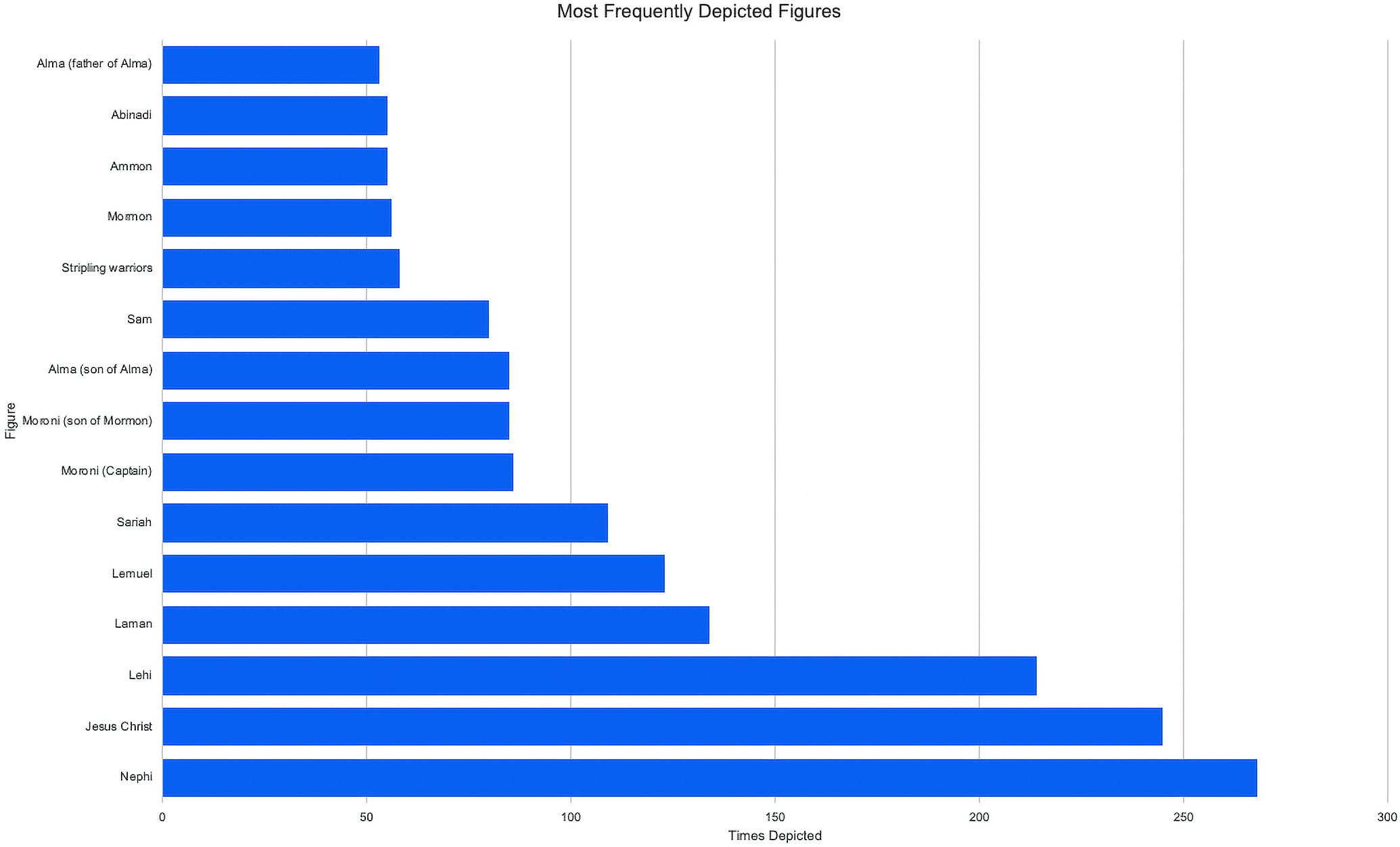

Similarly, certain individuals from the Book of Mormon get much more attention in the art than others (chart 4). The most frequently depicted figures are Nephi, Christ, and Lehi. Laman and Lemuel are depicted about half as frequently as Nephi but still more than the next most popular figures, which are Sariah, Moroni (the Captain), Moroni (the son of Mormon), Alma (the son of Alma), Sam, the stripling warriors, Mormon, Ammon, Abinadi, and Alma (the father of Alma). On the other hand, there are some topics and figures that have been depicted very few times, including Morianton’s maidservant, Hagoth, Corianton, the daughters of Ishmael, Giddianhi, Mosiah, Pahoran, and Helaman (although there are many artworks of his stripling warriors, there are only a handful of Helaman). And there are certainly others that do not show up in the art at all. Having this data will help artists and scholars consider why certain topics have received artistic attention while others have not and may even lead to the development of art based on less-common topics, figures, and interpretations.

Conclusions

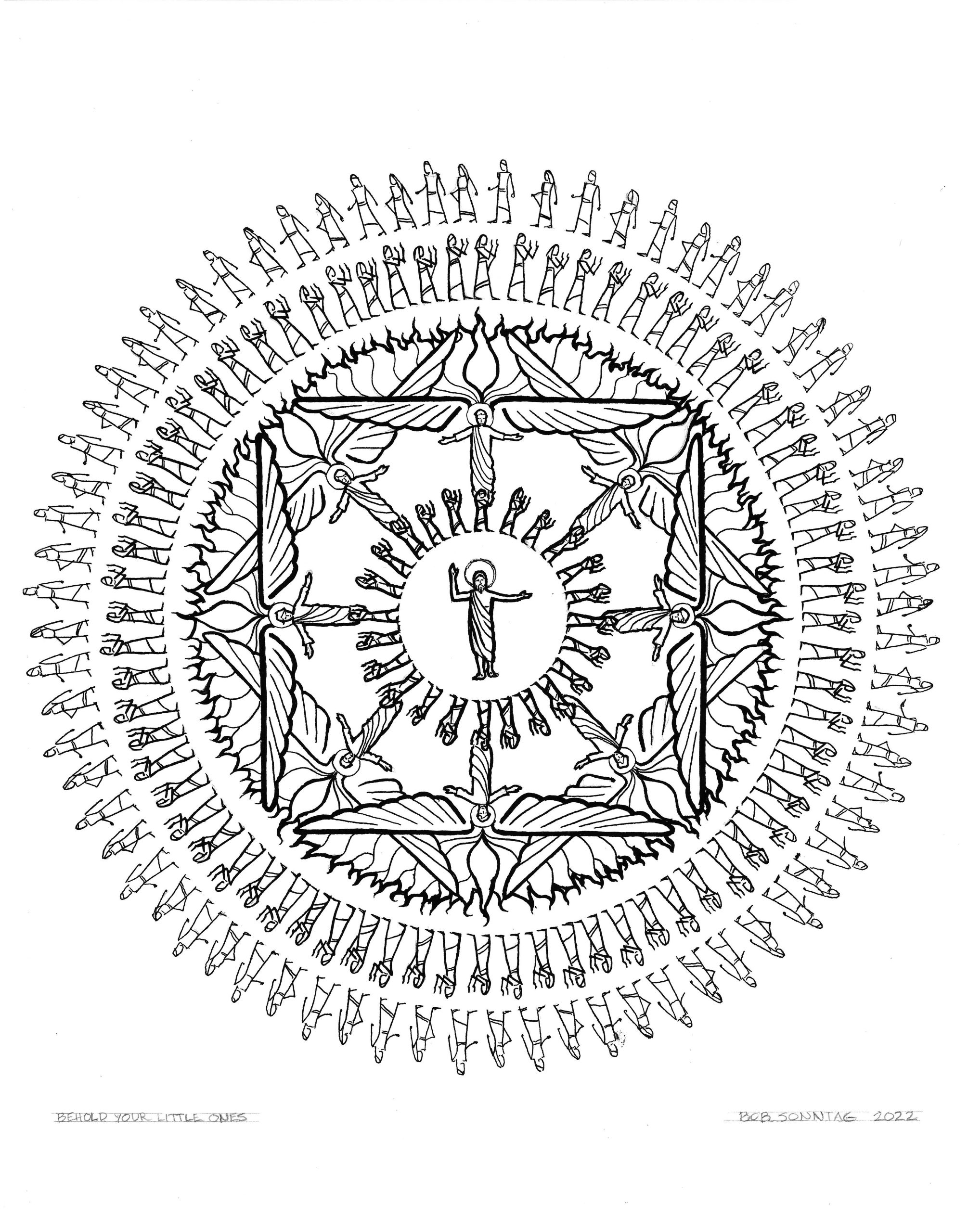

This data from the Book of Mormon Art Catalog unlocks many potential research topics, and the data observations presented here are just the tip of the iceberg. Moreover, the data will likely shift as the catalog expands. This is an ongoing, collaborative repository for Book of Mormon art—one that will continue to grow over time. There is a contact form on the website where users can suggest new artwork or additional information. Already, since the site launched in October 2022, many new artworks have been submitted and added. One example is the innovative drawing shown here by Robert Sonntag of Christ ministering to the Nephite children in 3 Nephi 17 (fig. 11).18

Apart from the catalog’s scholarly uses, it is a groundbreaking devotional tool for members of the Church to engage with the Book of Mormon and be inspired by it. The catalog’s website and social media pages include weekly posts with artwork and messages to supplement the Come, Follow Me curriculum. Users can even browse the artwork through these Come, Follow Me posts.19 Additionally, we are creating and sharing short video interviews with artists and scholars that help contextualize the artworks in the catalog and make them even more accessible to the public.20

On a personal note, building this database has allowed me to immerse myself in the Book of Mormon and the artwork based on it. As I looked at each image to catalog the various figures, symbols, and scripture references, I often had the scriptures open at the same time, and the process helped me explore the Book of Mormon in a new and fruitful way. In 3 Nephi 11, when Christ appeared in ancient America, the Nephites “heard a voice as if it came out of heaven; . . . and notwithstanding it being a small voice it did pierce them that did hear to the center” (3 Ne. 11:3). And with this piercing, still voice, God commanded, “Behold my Beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased, in whom I have glorified my name—hear ye him” (3 Ne. 11:7). For me, the painting His Marks by Jorge Cocco Santángelo, with its fractured space and flat planes of color, captures this feeling of sacred stillness (fig. 12).21 As the Savior reveals the wounds in his hands and feet, the crowd responds with awe and reverence. I imagine a kind of deafening silence as the people take in the moment. Looking at this painting makes me wonder, in my own busy life, if I can find ways to make time for quiet and awe. Like these Nephites, do I sit still and pay attention and listen to the promptings of the Spirit? Or in what ways could I better allow space for God to reveal himself in my life?

Work on this project has also facilitated rewarding interactions with generous scholars, artists, curators, and collectors. I am inspired by the ways in which artists are engaging with the Book of Mormon to illuminate its message and meaning. One goal of the catalog website is to help artists reach a broader audience. In the early stages of the project, artist Annie Poon provided feedback on how the site could best meet the needs of artists, and she continued to support the endeavor in a variety of ways. She also allowed us to publish her recent series of fifty Book of Mormon prints, making them available to the public for the first time.

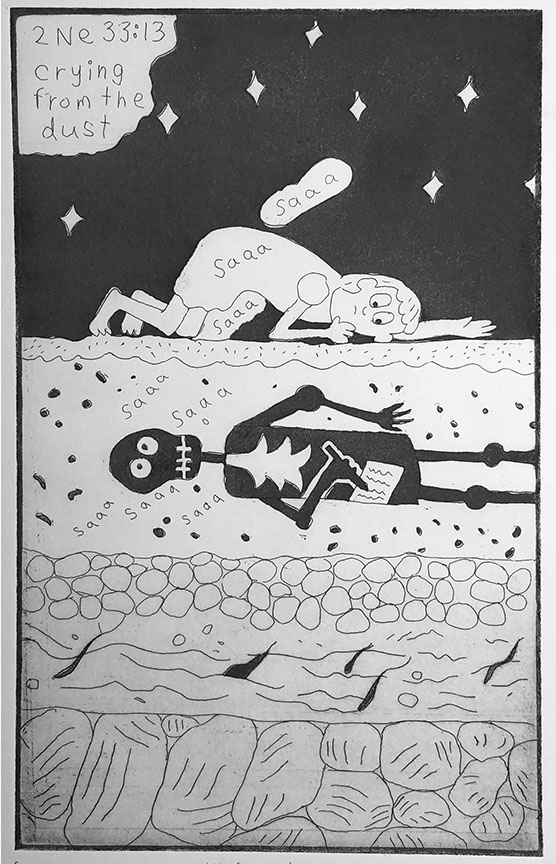

One of these etchings is Whispers, which visualizes Nephi’s declaration that through his written record he speaks “unto you as the voice of one crying from the dust” (2 Ne. 33:13, fig. 13).22 Poon’s light-heartedly macabre image shows Nephi—now a skeleton long since dead and buried underground—still clutching a stylus and writing away. Nephi’s whispers of “saaa, saaa, saaa” float up from him to reach the listening ear of a living girl. With one ear pressed to the ground, the girl strains to hear this voice from the dust. In some ways, this image is emblematic of the Book of Mormon Art Catalog’s mission to recover the past, index the present, and pave the way for the future. The work of translation is typically understood as dealing strictly with text. Yet in the thousands of images in the catalog, I see works of translation too. I see people wrestling with scripture, making decisions about how to understand a scene or idea, and finding novel and creative ways to express their beliefs.

Visual art has a powerful impact on how we think about scripture stories, doctrine, and history. As Richard Oman has remarked, “The visual image helps reinforce gospel teachings, helps sink the message into the mind and the heart.”23 Art can be a wonderful method of communication and a medium for revelation and understanding. There are two sides to this coin, though, since art has the potential to constrain interpretation and connection when only one kind of art, one kind of figural depiction, or one kind of reading is viewed. Access to a greater variety and volume of art through the Book of Mormon Art Catalog provides an opportunity for scholars, artists, and members of the Church to be enriched both aesthetically and spiritually, to consider familiar scenes with fresh eyes, and to find inspiration in the scriptures.

About the author(s)

Jennifer Champoux is an art historian and the director of the Book of Mormon Art Catalog. She lives in Colorado with her husband and three children. She is deeply grateful for the generous financial and institutional support of the Laura F. Willes Center for Book of Mormon Studies, part of the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship at Brigham Young University, and particularly for the support of Spencer Fluhman and Jeremy King. Grant funding allowed for several fantastic BYU student research assistants: Noelle Baer, Emma Belnap, Candace Brown, Elizabeth Finlayson, and Aliza Keller. This project would not be what it is without their hard work and great ideas.

Notes

1. See Kristin Lohse Belkin, Rubens (London: Phaidon Press, 1998), 109–19.

2. See Mariët Westermann, Rembrandt (New York: Phaidon Press, 2000), 101–7.

3. George Q. Cannon, “To the Artists of Utah,” Deseret Weekly, March 8, 1890, 367.

4. Doris R. Dant, “Minerva Teichert’s Manti Temple Murals,” BYU Studies 38, no. 3 (1999): 6–32; Paul L. Anderson, “A Jewel in the Gardens of Paradise: The Art and Architecture of the Hawai‘i Temple,” BYU Studies 39, no. 4 (2000): 164–82.

5. See Linda J. Gibbs and Doris R. Dant, “Harwood and Haag Paint Paris,” BYU Studies 33, no. 4 (1993): 754–56; Dawn Pheysey, “Testimony in Art: John Hafen’s Illustrations for ‘O My Father,’” BYU Studies 36, no. 1 (1996–97): 58–82; Travis T. Anderson, “Seeking after the Good in Art, Drama, Film, and Literature,” BYU Studies 46, no. 2 (2007): 243; and Rachel Cope, “‘With God’s Assistance I Will Someday Be an Artist’: John B. Fairbanks’s Account of the Paris Art Mission,” BYU Studies 50, no. 3 (2011): 133–59.

6. Spencer W. Kimball, “The Gospel Vision of the Arts,” Ensign 7, no. 7 (July 1977): 5, emphasis original.

7. The catalog can be found at https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/.

8. Helaman recounts of his two thousand sons, “Yea, they had been taught by their mothers, that if they did not doubt, God would deliver them. And they rehearsed unto me the words of their mothers, saying: We do not doubt our mothers knew it” (Alma 56:47–48).

9. Kathleen Peterson, “Mothers of the Stripling Warriors,” Book of Mormon Art Catalog, https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/catalog/mothers-of-the-stripling-warriors/.

10. With thanks to Micah Christensen.

11. Arnold Friberg, “Nephi’s Family,” Book of Mormon Art Catalog, https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/catalog/nephis-family/.

12. I am grateful to Laura Paulsen Howe, art curator at the Church History Museum, for helping me locate and research Book of Mormon art in their collection, and to Carrie Snow, manager of collections care at the Church History Museum, who arranged for photography and image files of items.

13. Leta Keith, “Tree of Life,” Book of Mormon Art Catalog, https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/catalog/tree-of-life-34/.

14. David Hyrum Smith, “Lehi’s Dream of the Tree of Life,” Book of Mormon Art Catalog, https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/catalog/lehis-dream-of-the-tree-of-life-2/.

15. It should be noted that there may have been additional artworks during this period that are no longer extant. But it’s interesting to consider why there was a relative decline in artistic interest in the Book of Mormon during that time. While there are probably many explanations, it’s notable that the Church in that period encouraged Latter-day Saint artists to train and work in contemporary European approaches, particularly landscape painting, rather than narrative religious art.

16. The exceptions are one painting of Lehi’s dream by Avon Smith Oakeson and one of Christ with the Nephites by Mabel Pearl Frazer. Also, a series of comics based on the Book of Mormon by John Philip Dalby was published in the Deseret News from 1947 to about 1953. The Dalby series is currently being researched and added to the catalog. For more information on Dalby, see Ardis E. Parshall, “Dalby’s ‘Stories of the Book of Mormon,’ Table of Contents,” The Keepapitchinin (blog), April 9, 2020, https://keepapitchinin.org/dalbys-stories-of-the-book-of-mormon-table-of-contents/.

17. Book of Mormon Stories, 3rd ed. (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1997), https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/book-of-mormon-stories?lang=eng. For purposes of this study, out of these hundreds of illustrations, only the thirty that are also used in the Come, Follow Me manuals are included in the numbers.

18. Robert Sonntag, “Behold Your Little Ones,” Book of Mormon Art Catalog, https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/catalog/behold-your-little-ones-6/.

19. “Come, Follow Me,” Book of Mormon Art Catalog, https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/category/come-follow-me/.

20. Book of Mormon Art Catalog, Home [YouTube Channel], https://www.youtube.com/channel/UClTBj7npnhS8KWyg6KqiYoQ.

21. Jorge Cocco Santángelo, “His Marks,” Book of Mormon Art Catalog, https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/catalog/his-marks/.

22. Annie Poon, “Whispers,” Book of Mormon Art Catalog, https://bookofmormonartcatalog.org/catalog/whispers-book-of-mormon-series-12/.

23. “Mormon Art Portrays History, Doctrine and Beliefs of Church,” Newsroom, March 27, 2009, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/article/mormon-art-portrays-history–doctrine-and-beliefs-of-church.

- It Takes Two: What We Learn from Social Science about the Divine Pattern of Gender Complementarity in Parenting

- “Show Them unto No Man”: Part 1. Esoteric Teachings and the Problem of Early Latter-day Saint Doctrinal History

- Recorded in Heaven: The Testimonies of Len and Mary Hope

- Charity as an Exegetical Principle in the Book of Mormon

- The Book of Mormon Art Catalog: A New Digital Database and Research Tool

- “He Is God; and He Is with Them”: Helaman 8:21–23 and Isaiah’s Immanuel Prophecy as a Thematic Scriptural Concept

Articles

- That They May Be Light

Cover Image

- Salad Days

- After Anger

Poetry

- Joseph Smith and the Mormons

Reviews

- Every Needful Thing: Essays on the Life of the Mind and the Heart

- Perspectives on Latter-day Saint Names and Naming: Names, Identity, and Belief

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

After Anger

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X