Being Latter-day Saints (1841–1857)

Four Matriarchs in the Centreville, Delaware, Branch

Article

-

By

Marie Cornwall,

Contents

After Joseph Smith established The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he began sending missionaries to the eastern states. It did not take long before small branches began popping up in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Delaware. While many of the new converts joined with the main body of the Saints, first in Missouri and later in Nauvoo, others remained in their communities. With few exceptions, much of the history of the Latter-day Saints focuses on the migrations to Nauvoo and settlements in Utah.1 Available histories offer few details about community life among Latter-day Saints who remained where they converted. This article is a case study of the Centreville, Delaware, branch and the women who maintained the continuity of the branch from its establishment in 1841 until 1857 when a large contingent of the branch finally headed west. Who were these converts and what might we learn about the early Church by focusing outside an organizational history and away from the work of missionaries and local male leaders?

This case study is possible because of a unique set of primary historical records: (1) branch records that detail membership, baptismal dates, and departures for Nauvoo; (2) the journal of Samuel A. Woolley, a missionary on his way home from a proselyting mission in Calcutta, India, who arrived the end of February 1855 and remained through December, keeping a detailed record of branch activities; (3) family histories and genealogies posted on FamilySearch.org and other genealogical sites; (4) census, emigration, and pioneer databases; and (5) civil birth, marriage, and death records.

First, a brief lesson in the geography of the Centreville area and a history of missionary work will set the stage for further analysis. Second, a description of four matriarchs and their families, which consisted mostly of daughters, explores the relationships that existed among the branch members. The four matriarchs were among the first converts in the area, and their stories make clear how important they were to the success of the branch. The women described herein left no accounts of their lives. But recovering their history tells us much about the small communities that emerged in the early years of the Latter-day Saint experience.

Centreville, Delaware

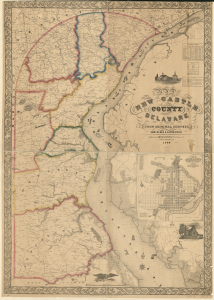

Centreville was located along the Kennett Pike in Christiana Hundred of New Castle County, Delaware (fig. 1),2 and remains an unincorporated subdivision of New Castle County today. A twelve-mile arc separates New Castle County, Delaware, to the southeast from Chester County, Pennsylvania, to the northwest. Centreville lies just a mile from that boundary on the Delaware side. By 1850, Centreville had become the regional center for the cattle trade and the transport of agricultural goods from the farms of Pennsylvania to Wilmington, Delaware. Farming dominated Christiana Hundred, but there was also work in the flour and cotton mills that came to populate the Brandywine Creek. Irenee du Pont bought land near the Brandywine in 1802 and established what became the Eleutherian Mill, which soon became the largest gunpowder producer in the country.3

Missionaries reported great success in the area beginning in the late 1830s and early 1840s. In a September 1839 letter, Elder Lorenzo Barnes, then a twenty-nine-year-old member of the First Quorum of Seventy, wrote of great interest in the gospel in Chester County, Pennsylvania, which was just a few miles from Centreville. He reported thirty new members and “many more . . . believing, whom I trust will obey the gospel soon.” Ten months later (July 1840), the new members numbered 107.4 In October, Erastus Snow wrote, “In Philadelphia and the country around, . . . the cause is onward with rapid strides: many sound, intelligent, influential, and wealthy men have embraced the gospel in that country. . . . All eastern Pennsylvania is literally crying out ‘come and help us,’ ‘send us preachers’ . . . and on the other side of the Delaware [River] it is the same.”5 By then, Elder E. Malin, a representative at an October conference of elders, reported 135 members in Chester County and the establishment of the Brandywine Branch no more than fifteen miles from Centreville.6 Outsiders began referring to the area as Mormon Hollow.7

By 1841, the gospel message had spread across the border into Christiana Hundred, and the Centreville Branch was created with William A. Moore as the presiding elder. Twenty-three-year-old Erastus Snow, who would become a member of the Quorum of the Twelve by the end of the decade, recorded accompanying Moore to Centreville in April where Moore had baptized nine persons. Soon four additional new members were baptized.8 By July 6, Moore reported at the Philadelphia conference twenty-seven new members in Centreville, of which nineteen were women.9

The detailed information that enriches this study comes from the journal of Samuel A. Woolley.10 Returning from a two-year proselyting mission in Calcutta, India, Woolley arrived in Centreville at the end of February 1855. He had family in the area (both in Chester County and in New Castle County) and hoped to convince his relatives to give him his inheritance so he could complete the journey home to his wife and children. However, his extended family was reticent because they did not want him to use the money to further the work of his new religion. He stayed in Centreville until the end of the year.11 Because he had no money of his own, he depended on the branch members for all his needs. For nine months, he would drop in unannounced for a bite of supper and a place to sleep at one or another member’s home, with the hope of breakfast the next morning. Because he kept a detailed journal, we not only know about the support he received from the members but also the daily activities of many members.

The Matriarchs of Centreville

Woolley mentions four women most frequently in his journal. They all joined the Church within two years of the branch’s founding, remained faithful during the difficult years that followed the death of Joseph Smith, and were related in one way or another to all but one of the participating branch members.12 They were mature women, between fifty-three and sixty-one, with considerable life experience by 1855. Their names are Ann McMenemy Mousley, Eliza Ann Stilley McCullough, Elizabeth Lancaster Carpenter, and Theresa Raymond Crossgrove.13

Ann McMenemy Mousley

Ann Mousley was forty-one and the mother of ten when she was baptized on March 25, 1841, along with one of her sisters and a daughter.14 A second-generation Irish immigrant, she had been married to Titus Mousley for almost twenty-four years at the time of her baptism. Though Titus never converted, he supported his family in the affairs of their church. He owned a cooper shop that manufactured and sold wooden tubs and buckets for the gunpowder manufactured at the Eleutherian Gunpowder Mill. Ann and Titus Mousley were well-to-do and lived in a large stone home that frequently accommodated the entire branch for worship services.15 They also had a large family, and Woolley records the activities and visits of all their children, but particularly the four single daughters, the young Mousley sisters ranging in age from fifteen to twenty-seven.16

The Mousley family, with Ann as matriarch, functioned as the center of the Latter-day Saint community. Her oldest living daughter, Margaret Jane, was married to Joseph Foreman, the branch president.17 Two sons, who lived nearby, were active participants in the branch. While her husband was never baptized, he traveled west when the family decided to go, as did her mother and other extended family members who had converted.18 She was friends with Eliza McCullough, as suggested by McCullough’s frequent visits to the Mousley home. Ann frequently hosted branch members at her home after branch meetings, and she helped care for immigrants arriving in the area. She also frequently hosted Woolley at her home.

When he arrived in Centreville, Woolley described Ann Mousley in glowing terms. No other female Latter-day Saint living in Centreville is given such a detailed description in his journal: “She is a first rate woman & enjoys the Spirit. She has 3 sons & 5 daughters living[. T]wo sons belong to the Church & are married & I trust the other will obey soon[. T]he married daughter & 2 single ones belong to the church & all appear strong in the faith & possessed of a good spirit. Bro Foreman (her son in law) is strong. Sister Mousley was glad to see me although personally a stranger to each other even not so in spirit & faith.”19

Ann Mousley’s success with bringing her children into the fold and her generosity to everyone in the area created strong community bonds both among Latter-day Saints and in the larger community; she seems to have had a charisma that garnered the respect of everyone. Her obituary noted her generosity and strength of testimony:

Mother Mousley, as she was familiarly called by her acquaintances, proved to be one of the most valiant for the truth. . . . She so influenced her nine living children that they all followed her example. Her house was always open to the servants of the Lord, and her voice ever heard strengthening their testimony. Kind to the sick and generous to the poor, thousands have loved her for her womanly sympathy. . . . When taken ill last Monday evening, she said she would soon depart, and with patience and love towards all, she quietly fell asleep in the Lord.20

Eliza Ann Stilley McCullough

Eliza Ann McCullough was forty-one and the mother of four almost-launched children when she was baptized April 5, 1841.21 Her husband of twenty-three years, John McCullough, was a farmer, and the family lived on an average-sized farm in Christiana Hundred.22 Eliza’s mother died when she was twelve, and her father died when she was fifteen, leaving her an orphan. She had only one brother. But her husband came from a large family of five brothers and three sisters,23 and though he was not interested in the new religion, others in the McCullough extended family joined, perhaps under Eliza Ann’s influence. A sister-in-law (Ann Mousley’s sister) was baptized as well as two nieces, daughters of two of John’s brothers.24 There may have been some tensions in the family as a result, as suggested by comments in Woolley’s journal.25

Of English descent on her mother’s side and Swedish on her father’s, Eliza was several generations American. The McCulloughs were well-known and respected citizens in the area. She was educated and well-versed in religious ideas. Her daughter Margarett was baptized a few days after Eliza Ann26 and later married John Carpenter, the son of Elizabeth Lancaster Carpenter, and a Latter-day Saint. Another daughter, Lydia, married Carpenter’s oldest son, James. The double marriage between the McCullough and Carpenter siblings created a bond that may have accounted for later conversions among the Carpenters.27

Eliza was likely known by the Church leadership in Philadelphia since she felt comfortable seeking their support.28 She seems to have also encouraged other women to join—for example, a neighbor and the two McCullough nieces. She did not go west with the others in 1857, but eight years later, at age sixty-five, she began the journey to Utah.

Elizabeth Lancaster Carpenter

Elizabeth Carpenter was forty-seven and the mother of twelve children (eight sons and four daughters) ranging in age from six to twenty-six when she was baptized on March 16, 1843. She was already the grandmother of four. Elizabeth had married William Carpenter, a Quaker, in 1816.29 Their son John was the first in the family to join the Church; he was baptized in April 1842. Elizabeth and her daughter Rachel were baptized almost a year later. And then over the next couple of years, her husband, William, and another daughter Elizabeth Jane joined as well.30

Elizabeth had deep ancestral roots in America. Her paternal fourth-great-grandparents met on the Mayflower and were married in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Her mother, of Irish descent, died in childbirth when Elizabeth was sixteen. She was the oldest child and likely had responsibilities for raising her four younger siblings after her mother died, especially the infant brother. The Stilley and McCullough families were both well-known, prominent, long-time citizens of Centreville.

Elizabeth’s husband, William, died of cancer in 1849.31 Their oldest son, James, inherited the family property handed down from his grandfather Samuel.32 Given inheritance laws of the time, Elizabeth’s personal financial resources may have been limited after the death of her husband.33 According to census records, she was living with her daughter Rachel Crossgrove in 1850.34 By 1860, she had moved to the home of Rebecca Ann Lackey, her oldest daughter.35 Woolley mentions visits of “the Sisters Carpenter” (Elizabeth and her daughter-in-law Margarett Carpenter) to Rachel’s home.36 According to branch records, another daughter, Elizabeth Jane, “believed the work was of god [sic] and She had no desire to be cut off but her husband was not willing for her to attend the meetings.”37

Although her daughter Rachel Crossgrove and her daughter-in-law Margarett Carpenter were part of the exodus in 1857,38 Elizabeth did not gather with the Saints in Utah. She had many more children in the area who had not joined with the Latter-day Saints, and she had no means of her own to finance the trip. Had she left in 1857 when other members did, she would have said goodbye to twenty-six grandchildren.39 Sister Elizabeth Carpenter passed away at the age of sixty-eight in Centreville in 1863.

Theresa Raymond Crossgrove

Theresa Crossgrove40 was forty-one and the mother of five children under the age of twelve when she decided to become a Latter-day Saint in 1843. She and her husband were farmers, and her brother, who was thirty-eight, lived with them. Her brother joined the Church in February, and then Theresa was baptized just two weeks later. Her husband, Charles Wright Crossgrove, joined the very next week, and then several of his siblings converted the following year.41

Theresa Crossgrove was a first-generation immigrant from Switzerland. She arrived in the United States as a fourteen-year-old with her father and two brothers and soon became an indentured servant42 until she married Charles Crossgrove. According to the 1850 Census, Theresa and Charles owned an average-sized farm in Christiana Hundred and had a family of five girls and two boys.43 They had purchased the land just after they married and were newcomers in the area. Charles died in 1852, leaving Theresa to raise the children on her own.44 The oldest was twenty-one, but her two youngest children were only seven and four years old when her husband died. In her husband’s will, Theresa was named executrix (female executor of a will) along with her son James. Theresa and her brother Francis continued to run the farm together.

Theresa faced the trauma of losing her mother when she was just seven years old.45 Unlike the other three matriarchs, she likely never had the benefit of formal education in America and may not have learned to read or write in English until she was much older, if ever. Woolley described her as “from the old country, some place in Germany”46 and often visited her home and read to her and her brother Francis.47

Theresa Crossgrove’s baptism initiated the interest of her husband and several Crossgrove siblings and children. Her brother-in-law, Joseph Crossgrove, became a member in 1844 and later married Rachel Carpenter. Her children were young when she and Charles were baptized, and by the end of 1854, none of the children were baptized. By then, her two older daughters had married and were apparently uninterested. But Woolley was pleased to record the baptism of thirteen-year-old Sarah48 and sixteen-year-old Mary Ann in 1855.49 The next year, the oldest son, James, and the daughter Olive were also baptized. By the time Theresa Crossgrove’s family left for Utah in 1857, eight-year-old Josephine had also been baptized.50

Although she was executor of her husband’s will, her financial resources may have been limited, again by property laws. When she joined the others migrating to Utah, her brother Francis remained in Centreville to take care of the farm until it could be sold.51 Although the farm was eventually sold, problems with the title created an opportunity for the buyer to renege on the agreement. She and Francis were never able to receive full payment.52

In her obituary in the Deseret News, Theresa was described as an industrious woman who “passed through” forty-two years of widowhood, most of it in Bluffdale, Utah. The obituary continues: “She was ever sympathetic and hospitable to those suffering affliction or experiencing distress, never having been heard to complain during her eventful life. Her soul was ever Joyous in the knowledge that she had been permitted to receive the Gospel as restored through the Prophet Joseph Smith.”53

Latter-day Saint Religious Life in the Centreville Branch

Woolley’s meticulously kept journal offers clues to the everyday life of Latter-day Saints who did not gather with the body of the Saints. His journal also gives evidence as to how women converts contributed to the Latter-day Saint community.

Participation in Branch Meetings

Women participated fully in the regular “communion meeting[s],” as Woolley referred to them. Woolley describes his first meeting in the branch; he and Branch President Foreman spoke, “Sister [Eliza Ann] McCullah [sic] prayed, Sister Margaret Carpenter spoke, Sister Sarah Mariah Mousley sang a hymn, So all done as St. Paul said ‘if any have the spirit of exhortation, let them exhort, if any have a Psalm (Hymn) let [them] sing it.’” Sister Eliza Ann McCullough also spoke at a gathering at Rachel and Joseph Crossgrove’s home after a baptism in Brandywine Creek. Woolley opened with prayer, and “Sister McCullah [sic] made a few remarks.”54 Other entries merely note that both sisters and brethren spoke, without mention of exactly who. It is worth noting that in the 1850s, women were often not allowed to participate in church services, except among the Quakers. These women, however, both prayed and spoke publicly.

Baptisms, Blessings, and the Sacrament

In addition to participating in weekly meetings, the women of the Centreville Branch contributed to the members’ spiritual life by calling upon and recognizing the power of the priesthood. The Centreville families kept Woolley busy giving healing blessings to adults and children who were sick. The Crossgrove and Foreman women regularly requested blessings for their children. After Rachel and Joseph Crossgrove lost their two-year-old son, their four-year-old was suddenly taken ill. Rachel sent for Woolley to administer to him. Woolley recorded in his journal, “He was up in less than one hour, & playing about. [And] in the course of two hour eat [sic] a hearty supper. . . . [H]e had not eat any thing for two days his throat was very sore & much swelled [sic].”55

In November 1855, several members were sick or injured over the course of just two days. Woolley recorded the experience in his journal:

I administered to Sister Amanda Mousley three times during the day & evening as she is quite sick with fever, cold, & sore throat, etc. I administered to Bro. G. W. Mousley’s little son who is afflicted but is much better since I administered to him yesterday. Amanda felt better after being administered to. I administered to Sister Elizabeth Mousley (Wm’s wife) as she had scalded her hand pretty bad. Also to sister Crossgrove’s (the widow) little daughter (seven years old) Josephine, for her face as it is poisoned.56

Women requested priesthood blessings on other occasions as well. Elder Jeter Clinton was visiting in Centreville for a couple of days in September 1855. According to Woolley, during that time “Sister [Eliza Ann] McCullah [sic] & Pratt were here. Bro. J. Clinton & I blessed Sister McCullah [sic] by her request.” The next evening Sister Mousley, Martha Ellen, and Sarah Mariah Mousley also received priesthood blessings from Brothers Clinton and Woolley.57 Such requests were infrequent from the men in the branch.

When new converts were baptized during the summer of 1855, gatherings at the Brandywine River just below Chadd’s Ford brought branch members out in celebration. On Sunday, October 21, Woolley had performed three baptisms, including Ann Mousley’s daughter Wilhelmina.58 Two days later, Margarett Carpenter dropped by the Crossgrove home where Woolley had stayed the night to ask that her eleven-year-old son be baptized (grandson of Eliza Ann McCullough and Elizabeth Carpenter). Word spread, and the Saints gathered quickly. Soon there were four to be baptized: the Carpenter and McCullough grandson, Theresa Crossgrove’s daughter, and two more of Ann Mousley’s daughters. After confirming those baptized, the brethren administered to and blessed Sister Margarett Carpenter and Sister Sarah Taylor.59

Visiting among the Saints and Hosting Gatherings

Woolley frequented some households more than others, so his accounts are only of the visits he observed. But there are enough accounts to suggest that the women frequently visited in each other’s homes. He recorded that Eliza McCullough “was over to spend the afternoon [at Mousleys’], talked some to her & the rest . . . more pleasant than it has been for some time.”60 He noted an occasion when “the sisters Carpenter” (Elizabeth Carpenter and her daughter-in-law Margaret McCullough Carpenter) visited Rachel Crossgrove’s home,61 and another when the Mousley sisters visited and had supper with the widow Theresa Crossgrove.62 The women also sometimes traveled together to church conferences in Philadelphia and enjoyed dinners and informal gatherings.63

When the branch was first organized and small, sacrament and council meetings were convened at Rachel and Joseph Crossgrove’s home or the home of Ann and Titus Mousley. Church members also gathered informally for an afternoon or evening of food and gospel discussions. Joseph and Rachel Crossgrove often hosted these gatherings. Woolley describes a November 1855 gathering on a Tuesday afternoon at their home. The attendees included two missionaries, the two older Mousley sisters, the young widow Margarett Carpenter, two newly arrived English immigrants (both also single) and Eliza Ann McCullough’s neighbor who was widowed and would be baptized the next month.64

Subscriptions to Church Publications

Elder John Taylor launched the periodical the Mormon in the winter of 1855, instructing local leaders like Woolley to encourage the members to subscribe.65 Woolley notes that payment in support of the publication would be credited as tithing. Typically, payments to the Mormon were made by men, but Lydia Carpenter (Eliza McCullough’s daughter who married Elizabeth Carpenter’s son James) gave Woolley money for a six-month subscription.66 She was not a member, but she may have purchased the subscription for her mother.

Eliza McCullough had a subscription to the St. Louis Luminary. Woolley’s visits to her home during his ten-month stay in Centreville were always about reading the periodical; he never stayed for dinner or supper. Erastus Snow published the St. Louis Luminary to strengthen the Saints in the greater St. Louis area. Eliza Ann and her daughter Margarett Carpenter had heard Erastus Snow preach, and although he did not baptize Margarett, Snow was present at her baptism and likely confirmed her a member. The paper published epistles from the First Presidency, doctrinal treatises, and news from the Salt Lake Valley. Snow also republished Orson Pratt’s writings from the Millennial Star.67 While Woolley visited other homes and read to the occupants, he never mentions reading at the homes of Eliza Ann McCullough or Elizabeth Carpenter. They may have been the most educated of the matriarchs.

Generous Support for Missionary Efforts

The women of the Centreville Branch were particularly generous in contributing to the well-being of members in need. Because of his two-year missionary journey to Calcutta, Elder Woolley must have come to look particularly shabby. Although clean, his clothes had not been replaced for some time. Soon the sisters of the branch were gently taking care of him. Toward the end of March, Ann Mousley washed a shirt and garment and gave him “a nice white Linen Hdkf [handkerchief].” Her daughter Wilhelmina washed the new handkerchief and the one he already had. Two days later, Eliza Ann McCullough dropped by to spend the afternoon with Ann Mousley and while there gave Woolley “a silk pocket Hdkf.”68

At a May 1855 sacrament meeting, Brother Foreman read a letter from Brother Jeter Clinton announcing that Woolley would “take charge of the Church in [what would be called] the Delaware Conference.” Woolley then spoke to the group about sustaining and assisting one another: “The vote was carried unanimous by both the English & American Saints in the affirmative. . . . They all agreed to raise a fund, which they would do by weekly or monthly paying in a certain amount. This I was counciled [sic] to do by Bro Taylor & all the Branch were willing to carry it out.”69 The next Friday, Eliza Ann McCullough dropped by the Mousley’s to leave Woolley a shirt she had made him, likely her effort to sustain and assist him personally.70 On Monday, Ann Mousley gave him $1.50 to buy a new vest.71

In July, Ann Mousley collected $1.00 from Theresa Crossgrove and $1.00 from her brother and added $1.00 from herself. She instructed Woolley to buy a pair of pants with the $3.00 (equal to about $90 today). Their generosity touched him. He recorded in his journal that “[I] never intimated to her that I wanted any, but she see I kneaded [sic] them, & May the Lord God of Israel bless them & particularly Sister Ann Mousley for her kindness not only in this thing but many others yet unnumbered by me. I say may she & they be blessed, not only in this time, but also be rewarded over again in the resurrection of the just, & be saved & exalted in the Kingdom of God.”72

The sisters continued their generosity, with no indication that Woolley might be overstaying his welcome. Sister Pratt, an English convert, gave Woolley seventy-five cents to buy a handkerchief. Sister Eliza Ann McCullough gave him fifty cents for the fund to assist the members. He blessed them both in his journal. Toward the end of September, he received more gifts. Sister Eliza Ann McCullough gave him seven yards of white flannel to make garments. Once again, he was effusive in his journal:

I say in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ may the above blessing be hers also. I feel to thank these sisters, & also the Lord God of Israel, for their acts of kindness [toward me], for it is through His Goodness & blessing to me that I receive it. . . . I will testify before God in a coming day of those good deed for said our Lord & Savior, “if ye do it unto one of the least of my Servants ye do it unto me.” So they have administered to my wants as a Servant of God & “they shall in no wise loose [sic] their reward.”73

In October, as the weather began to turn cold, Sister Mousley and her daughter Sarah Maria organized the sisters, collecting $10.50 (equivalent to $320 today) for Woolley to buy himself a coat. He recorded the donations with the same precision he recorded subscriptions to the Mormon or the branch fund to assist members:

Ann Mousley ($2)

Sarah Maria Mousley ($1)

Martha Ellen Mousley ($0.50)

Eliza McCullough ($1)

Rachel Crossgrove ($1)

Margaret Carpenter ($1)

Sarah Taylor ($0.50)

Sarah [Langton] Lancton ($1)

Lucy & Emma Stradwick ($0.50)

Eliza Kemp ($0.25)

Selina Hodgins ($0.25)

Elizabeth Carpenter ($0.50)74

His gratefulness for the gifts was as effusive as previous entries that asked God to reward those who made these contributions. He wrote,

I pray our Father who art in heaven to bless them all & I bless them in the name of His Son Jesus Christ & by the authority of the Holy Priesthood, & say they shall be blest in time & eternity, & if faithful shall receive a hundredfold, & also be recorded in the Resurrection of the just, which may God grant for Christ’s, Amen. I feel to thank those who gave me this amount, & would say to others where the Elders are, “go & do likewise.” . . . The sisters done first rate, & my heart is full of blessing from them & I know God’s hands are full for them as soon as they are prepared to receive them.75

These contributions by Centreville’s women were repeatedly noted by Woolley. He acknowledged the importance of what they were doing, just as he acknowledged the contributions made by the men in the branch—subscriptions to the Mormon, gifts to the fund to assist members, and their willingness to travel to the homes of members to give blessings. However, the domestic work that sustained the community—preparing meals, offering shelter, caring for the sick, and more—was not reflected in Woolley’s records. As many have suggested, the domestic work of women was invisible to their contemporaries. The same holds today; invisible work, by definition, cannot be valued.76

Responding to Requests from Presiding Authorities

The route taken by Latter-day Saints emigrating from England and Europe changed in 1855. Before 1855, immigrants were landing in New Orleans and traveling up the Mississippi River. Cholera often broke out along the route, and so, in 1855, ships carrying Latter-day Saints began arriving in Philadelphia and New York.77 While many immigrants continued their journey west immediately, a few remained in the East for a season to acquire the necessary resources to continue their journey. John Taylor, presiding elder of the Eastern States Mission, was given the responsibility to oversee the Saints arriving on ships from England and Europe.78 Taylor delegated some of the work to Samuel Woolley. Woolley busied himself during April and May helping the newly arrived find accommodation and employment in and around Centreville.79 The Centreville Branch was soon welcoming weary travelers from England. The women of Centreville supplied food and shelter with little advance notice for when the immigrating Saints would arrive.

Woolley gave only passing attention to the ways the Centreville sisters cared for the arriving converts. However, he offers many clues as to their contributions—for example, how many English Saints arrived and where they were staying and who he called upon in emergencies. In addition to their domestic tasks, the women were ready to help in whatever way they could, although care for their own families sometimes got in the way. The week the first group of Saints arrived, Margaret Jane Foreman (Sister Mousley’s daughter) likely wanted to help her mother care for the travelers, but she had three children down with the whooping cough.80

The first group of immigrants arrived in the latter part of April 1855. Woolley delivered sixteen adults and five children to Wilmington. Titus Mousley met them in the Dearborn81 and brought a wagon for their luggage. The travelers had to walk the eight miles to Centreville. Sister Ann Mousley and her daughters greeted them kindly. They had prepared supper for all with less than twenty-four hours’ notice. Woolley makes no mention, but it is likely that other sisters in the branch delivered additional food to help feed the group. While Woolley, Foreman, Mr. Mousley, and his sons William and Washington looked for housing and jobs for the immigrants, the sisters of the branch fed them and gave them a place to sleep.

The second group arrived two weeks later, this time seven men, six women, and six children. When everyone gathered for services on Sunday, there were more English Saints than American. Another four women arrived on the 23rd. This time, Brothers Foreman and Crossgrove met the group in Wilmington and delivered them to Rachel and Joseph Crossgrove’s home.82 Theresa Crossgrove had loaned her Dearborn carriage and horse to manage the luggage belonging to the English Saints. Ann and Titus Mousley sent two English families “a fine piece of pork . . . &tc. as a present & sent them on loan 4 chairs a tea kettle, Duch [sic] oven, two pichers [sic], tin pan &tc.”83

Initially, much of the hosting was done by the Mousley family. As more immigrants arrived, other members of the branch provided space and meals. Woolley wrote in his journal that he had made his home at the Mousley’s, but just two weeks later he found there was little room for him, and he more frequently called in at the home of his Aunt Sarah, who lived in Wilmington, or Rachel Crossgrove or Theresa Crossgrove for his meals and a place to stay the night. By the end of May, forty-four English Saints and sixteen of their children had arrived in the area. The women of Centreville Branch were likely busy during the first few weeks making sure the visiting Saints had what they needed—whether it was food, cooking tools, or provisions to cook for themselves.

The sisters also assisted Woolley when emergencies arose. In mid-May, Woolley had discovered one English sister “had had nothing to eat for near 2 days except a little rice.” Elizabeth Mousley (wife of Washington Mousley), though not yet a Latter-day Saint, was tasked with sending the sister something that would stay down and calm her stomach.84 When it was discovered that an English couple was unable to provide for themselves, the widowed Theresa Crossgrove agreed to allow them to board with her. The husband was so unwell that he was unable to work. What was to be a few days, became several weeks.85

On May 31, Sister Margaret Jane Foreman found herself caring for twelve-year-old Emma Stradwick who ran into trouble at her housekeeping job:

This morning after breakfast Sister Stradwick’s daughter Emma came down and told me [Woolley] that her Mistress, Mrs. Nickles said she must leave them to day & that she had charged her with stealing money & giving it to me. So I went up to see what was wrong. I found that she had been guilty of stealing, for which I gave her a sharp reprimand for, but it was falce (sic) about her giving me any money at any time. So I took her away brought her down & left her in Sister Foreman’s care. I then got Father Mousley’s horse & Dearborn to go to Wilmington to meet the Brethren & Sisters from Phila[delphia].86

By the end of May, Woolley was feeling a bit overwhelmed, as he reported in his journal: “Just after I got here, I was consoling my self with having finished my job of getting places for and taking the Brethren to it, up walked 5 more which Bro. Clinton had sent out here to me to see to & provide for &tc. So I see it is still as it always has been with me, in this Church, & perhaps always will be for aught I know, as soon as one job is off my hands another is on & so it goes.”87

The sisters of the branch were likely feeling much the same; in just a few more days, another group of immigrants would arrive in Centreville needing food and temporary shelter. The women of Centreville had no more idea than Woolley how many more immigrant Saints were going to arrive in Delaware.

Woolley relied heavily on the women of Centreville to help manage the settling of the English Saints, though in his journal he does not specifically address the work they did. In June, when Woolley learned that the Mousley’s were once again hosting several English Saints at their home after the Sunday meeting, he wrote a blessing in his journal for Father Mousley: “May the God of Israel bless him for ever & ever in the name of Jesus Christ, Amen. They also have 3 strangers from Phila[delphia] which marks 8 besides his own (large) family here tonight.”88 Though Mousley certainly deserved the blessing, given all he had done to support the immigrants, the lack of any word that recognized the work of the women suggests that their work was at the very least partially invisible to him. The lack of blessings is in stark contrast to his effusiveness when the sisters offered him gifts of clothing. That was not invisible to him.

Conclusion

The importance of women to the growth of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in and around Centreville, Delaware, is apparent in this history. Erastus Snow’s description of intelligent, influential, and wealthy men joining may have been true.89 But a more accurate statement would have noted that many new converts were women. Among the twenty-seven members of the newly established Centreville Branch, seventy percent were women. And some were prominent women within their communities. Perhaps even more surprising, we learn that women were converting without their husbands. Less surprising, given what we know about the importance of social networks in the process of conversion, the new converts were introduced to the Church by family members.

Though the conversions were steady over time, there is no evidence of mass baptisms or large family groups being baptized all together. Instead, baptisms occurred in groups of four or nine or six people at a time. Relatives of early Church converts—husband and wives, brothers and sisters—did not convert at the same time. The Mousley, McCullough, Carpenter, and Crossgrove siblings followed one another into baptism, but the time span between baptisms ranged anywhere from a week to more than three years.

Conversion created part-member families. The same networks that facilitated conversion also kept women from joining with the main body of the Church in the West. All four matriarchs were baptized without husbands. Titus Mousley was supportive though not converted. John McCullough was not interested, and neither were two of their three children. Elizabeth Carpenter’s husband joined two years later, but only four of her eleven living children converted. The rest were not interested. Theresa Crossgrove’s husband was converted, but he died young; two of her oldest daughters did not join. These relationships kept the four matriarchs bound to Centreville.

The daily activities of the Latter-day Saints mirror modern activities such as paying into a fund to support the poor, visiting members, performing blessings, organizing to help the new immigrants, meeting together to discuss the gospel, and more. The women were an integral part of those activities despite the lack of a formal Relief Society. Much of the community work described by Woolley was directed and carried out by women. They visited and supported one another in the faith, participated in religious gatherings, and called for priesthood blessings to benefit them and their families. They cooked meals and managed their homes such that they could accommodate any guest at any time, whether it be a missionary, a branch member, or a new convert just arrived from England. They studied the gospel and kept up with Church news by subscribing to regional publications. They saw to it that their children were taught the gospel and were baptized, and they encouraged family and friends toward baptism. They contributed to the missionary work by making sure Samuel Woolley was a presentable representative of the Church and gave him money to purchase clothes or fund his travel.

The women may have wanted to join with the rest of the Saints in Utah, but none had the financial resources to make the journey. Elizabeth Carpenter was living with one or another of her adult daughters. We do not know if she had any liquid assets that would facilitate a journey west, but we do know that her oldest son had inherited the family farm. Eliza Ann McCullough’s husband was not a member, and she likely had few assets to go it alone. Her daughter, Margarett McCullough Carpenter had always planned to go west, but John Carpenter died young of consumption. She had four children under the age of eleven and lived with her parents because she had no assets of her own. Theresa Crossgrove was also constrained by the lack of liquid assets. For reasons that remain unclear, she had trouble selling her farm and, when she finally did, was never able to receive full compensation. Her brother, Francis, remained behind to manage the estate. Both Margarett and Theresa were able to travel west because of the generosity of Rachel and Joseph Crossgrove, who sold their farm and purchased three wagons and oxen. They offered one wagon to Margarett Carpenter and the other to Theresa Crossgrove. The branch fund to assist the poor was given to Margarett to buy supplies and prepare for the journey.

We also learn that their staying in Centreville benefitted other Latter-day Saints attempting to make the journey to Zion. Just as some of the Nauvoo Saints remained on the prairie for five or more years to help others make the long journey to Zion, the Saints who remained in the East were vital to the journey of the Saints who crossed the Atlantic without the means to continue their journey once they arrived in America.

Why did two of these four women finally decide to gather with the Saints two years after Woolley left the area? First, in Ann Mousley’s case, her husband, Titus, was willing to go despite his reticence to be baptized. Second, both were able to acquire the necessary resources for the journey. Third, they may have gathered for the sake of their daughters. There may have been growing awareness of the consequences for women who did not marry within the Church. Only three young women converts had found a mate among members of the Centreville Branch—Margarett McCullough Carpenter, Rachel Carpenter Crossgrove, and Margaret Jane Mousley Foreman. Others, like Elizabeth Jane Carpenter, married nonmember husbands and then found it difficult to continue participating. Both Ann Mousley and Theresa Crossgrove had four single daughters. Whom would they marry?

Eliza Ann McCullough and Elizabeth Carpenter remained behind. Neither had the means to move and were tied to the community because of children and grandchildren. Elizabeth Carpenter died in Centreville in 1863; she was sixty-eight. Eliza Ann McCullough began her journey to Utah after the death of her husband and her good friend Elizabeth Carpenter. Her daughter, Margarett, was living in Utah, had married again, and had another child. She wanted to see her grandchildren and join with other members of the Church in Zion. In 1865, she began the journey but died en route in Wyoming, Nebraska—the outfitting station where travelers began their overland trip.

This case study of the women of Centreville offers insight into the early days of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the significance of women’s readiness to respond to the message missionaries brought. As a case study, it offers clues, but until further research can examine how communities of women built the kingdom, more evidence is required to draw firm conclusions.

One final note is necessary to demonstrate the usefulness of analyzing communities of women. When branch members left Centreville in 1857 to gather with the Saints in Utah, the group had to hire seven teamsters to handle the oxen and wagons. There were twenty women and twelve men in the Jacob Hofheins Company. They were traveling with forty children and teenagers under the age of eighteen. Thirty-two of the children were under age twelve.90

According to family history, the Mousley daughters arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with great fanfare in their father’s Dearborn carriage. More importantly, twenty-nine members of the company were the children and grandchildren of the four matriarchs of the Centreville Branch. They joined another five grandchildren already living in Utah, and more grandchildren would be born in the ensuing years. The importance of women for raising the next generation of Latter-day Saints must not be ignored but neither should their other contributions. Though from very different backgrounds and social stations, these sisters sustained each other temporally and spiritually for many years in the little village of Centreville. And in doing so, they sustained a community that contributed to the strength of a small but emerging religion.

About the author(s)

Marie Cornwall is Professor Emerita, Sociology Department, Brigham Young University. She taught sociology courses for over thirty years at BYU and was for a time the director of the Women’s Research Institute. She taught the sociology of gender and courses on the family and social change with a focus on documenting the changing lives of women in Utah and the United States. She helped establish the Aileen H. Clyde 20th Century Womens Legacy Archive at the University of Utah Marriott Library, conducting dozens of life history interviews with women born in the early part of the twentieth century. Since retiring, she has been writing the histories of her women ancestors who became Latter-day Saints between 1841 and 1861 in Ireland, Scotland, England, Canada, and the United States.

Notes

1. Stephen J. Fleming, “‘Congenial to Almost Every Shade of Radicalism’: The Delaware Valley and the Success of Early Mormonism,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 17, no. 2 (2007): 129–64; Stephen J. Fleming, “‘Sweeping Everything before It’: Early Mormonism in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey,” BYU Studies 40, no. 1 (2001): 72–104. See also David J. Whittaker, “The Philadelphia Pennsylvania Branch: Its Early History and Records,” Mormon Historical Studies 6, no. 1 (2005): 53–66.

2. “Hundred” was the term used for the representative boundaries in the Delaware Assembly. “Chapter 6—Boundaries of Certain Hundreds in New Castle County,” 105th General Assembly, Delaware General Assembly, https://legis.delaware.gov/SessionLaws/Chapter?id=35821.

3. Henry Seidel Canby, The Brandywine, Rivers of America series, ed. Stephen Vincent Benet and Carl Carmer (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1941), 140.

4. Lorenzo Barnes to Don Carlos Smith, September 8, 1839, in Times and Seasons 1, no. 2 (December 1839): 27–28. See also “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons 2, no. 1 (November 1840): 206–7.

5. Erastus Snow to Messrs Editors, October 31, 1840, in Times and Seasons 2, no. 2 (November 15, 1840): 221. See also Stephen J. Fleming and David W. Grua, “The Impact of Edward Hunter’s Conversion to Mormonism in Chester County, Pennsylvania: Henry M. Vallette’s 1869 Letter,” Mormon Historical Studies 6, no. 1 (2005): 133–38.

6. “Conference Minutes,” 216.

7. “‘Mormonism Is Rolling Along with All Power’ Says Letter of 1852,” Northern Chester County (Honey Brook, Penn.) Herald, May 1, 1952.

8. Erastus Snow, Journals, 1835–1851; 1856–1857, 1838 January–1841 June, 104, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, accessed December 7, 2023, https://catalog.churchofjesuschrist.org/assets/e6cc997c-1739-4acf-a9db-9185e6991036/0/0?lang=eng.

9. Philadelphia Branch Minutes 1840–1854, P27, 21, Library-Archives, The Auditorium, Community of Christ, Independence, Mo.; Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records and Minutes 1841–1845, Local Jurisdictional Record Books, P27, 1–8, Library-Archives.

10. Samuel Amos Woolley, Journal, 1854 April–1855 December, Church History Catalog, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, accessed September 28, 2023, https://catalog.churchofjesuschrist.org/assets/95e75ff8-8b5c-4173-b9fa-f07f2a3d84d6/0/2?lang=eng.

11. Woolley, Journal, 327 (April 18, 1855).

12. This claim is based on extensive research matching the names of branch members with 1850 Census information and information from FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com. Using the branch records and the Woolley journal, I first identified each person in the 1850 Census. The 1840 Census does not list individual family members. Because some members may have already left the area, individuals not found in 1850 Census were located using the Pioneer Database (now available as the Church History Biographical Database, https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/chd/landing), FamilySearch.org, and Ancestry.com. Census data and available vital statistic information (births, marriage, and deaths) were checked to verify the quality of online genealogical services. Clues to family relationships were also found in the Woolley journal and verified using the 1850 Census for Centreville, Delaware. Histories posted on FamilySearch.org were used as background, and facts were tested to the extent possible. Summary tables available from author.

13. Further information is available for each of these women on FamilySearch.org. Ann McMenemy Mousley (Ancestor ID: KWJY-8ZZ), Eliza Ann Stilley McCullough (KWVS-9QQ), Elizabeth Lancaster Carpenter (LLQ6-V55), and Theresa Crossgrove (KHD6-VJJ). Eliza Ann Stilley McCullough and Elizabeth Lancaster Carpenter are the author’s great-great-grandmothers.

14. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 1. Ann Mousley was baptized March 25, 1841, along with her sister Margarett McMenemy, and her daughter Margarett Jane Mousley.

15. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 3; “Titus Mousley [LZJL-FSJ] & Ann McMenemy,” Daughters of Utah Pioneers (DUP) History, FamilySearch, uploaded April 6, 2014, https://www.familysearch.org/photos/artifacts/6332115?p=53918803.

16. Woolley, Journal, 295 (February 27, 1855). See also FamilySearch information for Ann McMenemy Mousley (KWJY-8ZZ) and for dates when unmarried children were born: Sarah Maria Mousley (age 27), Martha Ellen Mousley (age 25), Ann Amanda Mousley (age 19), and Wilhelmina Logan Mousley (age 15).

17. Woolley, Journal, 310 (March 24, 1855).

18. “Titus Mousley,” Church History Biographical Database, accessed December 7, 2023, https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/chd/individual/titus-Mousley-1790.

19. Woolley, Journal, 296 (February 28, 1855).

20. “Died,” Salt Lake Herald, June 4, 1882, accessed December 4, 2023, https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/details?id=10652310.

21. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 1; Eliza Ann Stilley McCullough (KWVS-9QQ), FamilySearch, accessed December 7, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/KWVS-9QQ.

22. “United States Census, 1850,” entry for John McCullough and Eliza A McCullough, in FamilySearch, accessed December 15, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MHDM-M6M; accessed December 4, 2023, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/19341638:8054. The 1850 United States Federal Census for John McCullough lists him as a farmer with property valued at $2000.

23. John McCullough (LLQ6-VR4), FamilySearch, accessed December 7, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/LLQ6-VR4.

24. Elizabeth McMenemy McCullough (2R45-52Q) was baptized the same day as her sister Ann. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 1. Ann Elizabeth McCullough Westcott (LDM1-XPK) and Maria Louisa McCullough Clark (GWDK-KTK) were baptized April 13, 1842. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 2.

25. Woolley, Journal, 479–80 (November 23, 1855). Woolley reports a strange encounter with George Gould who was upset with him for teaching false doctrines. George Gould was the nephew of John McCullough, Eliza Ann McCullough’s husband.

26. Erastus Snow mentions baptizing four new members during his visit to Centreville (see note 8). Family histories report that Margarett McCullough was baptized along with her mother, but her name does not appear on the Centreville records. She may have been one of the four baptized by Erastus Snow. Family histories have always claimed she was baptized by Snow. Baptism date for Margarett McCullough is listed as April 11, 1841, on FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/ordinances/KWJK-JB4/.

27. James Lancaster Carpenter (LCMF-PV6) and John Steele Carpenter (KWV9-YZQ), FamilySearch.

28. Woolley Journal, 420 (September 3, 1855).

29. William’s parents, Samuel and Rachel Dingey Carpenter, were married in a Quaker meetinghouse. “Pennsylvania, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Marriage Records, 1512–1989,” entry for Samuel Carpenter and Rachel Dingee, June 17, 1773, FamilySearch, accessed December 8, 2023, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6CYX-KP7H.

30. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 2–3. John was baptized April 13, 1842. His sister, Rachel Carpenter, was baptized March 16, 1843, and his mother, Elizabeth Carpenter, was baptized March 16, 1843 (and then rebaptized March 19, 1855). Another Elizabeth Carpenter (likely his sister Elizabeth Jane, who did not marry until 1847) was baptized July 19, 1843. John’s father (William Carpenter) was baptized February 10, 1844.

31. “United States Census (Mortality Schedule), 1850–1880,” entry for William Carpenter, 1850, FamilySearch, accessed December 8, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M3DG-G3X.

32. The 1850 U.S. Census indicates James S. Carpenter was a farmer of land valued at $10,000. This was one of the largest farms in the area. His youngest brother, Alfred Dupont Carpenter, age twelve, was also living on the farm and not with Elizabeth. “Christiana Hundred. Census 1850,” entry for James S. Carpenter, FamilySearch, accessed December 15, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-D199-VWZ?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AMHD9-WPR&action=view.

33. Elizabeth was to receive some money from her father, James Lancaster upon his death. But probate records indicate those funds would not have been available to her until 1858. “Pennsylvania Probate Records, 1683–1992,” Chester, Wills book U–V, vol. 20–21 1850–1863, James Lancaster’s Will, FamilySearch, accessed December 15, 2023, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L99B-B9LN-R.

34. “Christiana Hundred. Census 1850,” entry for Rachael Crossgrace, FamilySearch, accessed December 7, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-D199-N1D?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AMHD9-367&action=view.

35. “United States Census, 1860,” entry for Martin Larky and Rachel A. Larky, FamilySearch, accessed December 8, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M4SW-B7S. Lackey was incorrectly transcribed as Larky.

36. Woolley, Journal, 310 (March 24, 1855), 311 (March 26, 1855).

37. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 10.

38. Both were members of the Jacob Hofheins Company (1857). “Margaret McCullough Carpenter,” Church History Biographical Database, accessed December 7, 2023, https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/chd/individual/margaret-mccullough-1822; “Rachel D. Carpenter Crossgrove,” Church History Biographical Database, accessed December 8, 2023, https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/chd/individual/rachel-d-carpenter-1825.

39. Calculated by counting the number of grandchildren born to each child by 1857. See Elizabeth Lancaster, Details, FamilySearch, accessed December 7, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/LLQ6-V55.

40. Theresa’s name is spelled in a variety of ways in the records. For example, her name is spelled “Trissa” in the branch records and “Therissa” in the 1850 Census. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/19341360:8054. Woolley spells her name Thrisa. See Woolley, Journal, 397 (July 31, 1855).

41. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 2. Branch record transcription spells the family name as Crosgrove. This is a transcription error. For example, the 1850 Census lists the family using the handwriting rules of the nineteenth century (Croſsgrove) which should be transcribed as “ss” and not just one “s.” The “ſs” should be transcribed as a double ss.

42. “Two Noble Women,” Deseret (Salt Lake City) Weekly, December 2, 1898, 14, https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/desnews10/id/3453/rec/1, uploaded to FamilySearch on May 10, 2018, https://www.familysearch.org/photos/artifacts/54053465; Aileen Schmutz, “Women of Faith and Fortitude [History of Theresa (Reymann) Raymond Crossgrove],” n.d., typescript, Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Salt Lake City.

43. “United States Census, 1850,” entry for “Chas Crofgnau” (alternate spelling of Charles Wright Crossgrove), FamilySearch, uploaded March 10, 2021, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-D199-NP5?i=72.

44. See Charles Wright Crossgrove on FamilySearch (LC8J-YM3); “1852 Delaware Will & Probate Record of Charles Wright Crossgrove, Last Will and Testament,” FamilySearch updated May 13, 2018, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/sources/viewedit/9LYY-XK7?context.

45. See Theresa Raymond (KHD6-VJJ) and Theresa’s mother (24LD-YX5) on FamilySearch.

46. Woolley, Journal, 315 (March 31, 1855).

47. Woolley, Journal, 297 (March 1, 1855); 397 (July 31, 1855); 398 (August 1, 1855).

48. Woolley, Journal, 328 (April 22, 1855).

49. Woolley, Journal, 455 (October 23, 1855).

50. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 8, indicates a “Jas L. Crossgrove” baptized in April 1856. She may have been rebaptized upon arrival in Salt Lake City, because other records indicate a November 7, 1857, baptismal date.

51. Francis is not a member of the Jacob Hofhein’s company, but he arrives in the Valley by the 1860 Census where he is living with Theresa. “Weber. Census 1860 | Summit. Census 1860 | Tooele. Census 1860 | . . . ,” entry for Francis Raymond and Theresa Crosscrow [sic], FamilySearch, accessed December 7, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9BSF-9Q1P?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AMH2W-RP8&action=view.

52. John D. T. McAllister, Journals, 1851–1906, vol. 3, 1858 January–1862 April, 172–73, Church History Catalog, accessed December 7, 2023, https://catalog.churchofjesuschrist.org/assets/1598b3e2-399a-4c4d-9419-7936361a0737/0/174?lang=eng.

53. “Two Noble Women.”

54. Woolley, Journal, 316 (April 1, 1855); 329 (April 22, 1855).

55. Woolley, Journal, 456–7 (October 24, 1855).

56. Woolley, Journal, 482 (November 27, 1855). Some creams used mid-nineteenth century contained toxic chemicals such as arsenic and iron. Josephine may have used some such product on her face.

57. Woolley, Journal, 420 (September 3–4, 1855).

58. Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 7.

59. Woolley, Journal, 453–55 (October 23, 1855). The Mousley daughters were rebaptized, as was the custom in the early days of the church.

60. Woolley, Journal, 314 (March 30, 1855). The reference to being more pleasant is personal to Woolley. In the early days of his visit in Centreville, he frequently notes how nice it is to be with Latter-day Saints once again.

61. Woolley, Journal, 311 (March 26, 1855).

62. Woolley, Journal, 359 (June 6, 1855).

63. Woolley, Journal, 442–47 (October 6–13, 1855).

64. Woolley, Journal, 471 (November 13, 1855).

65. John Taylor, Mormon, 1855–1857, accessed December 8, 2023, https://archive.org/details/TheMormom18551857/mode/2up.

66. Woolley, Journal, 312 (March 28, 1855).

67. Susan Easton Black, “St. Louis Luminary: The Latter-day Saint Experience at the Mississippi Rover, 1854–1855,” BYU Studies 49, no. 4 (2010): 160–62.

68. Woolley, Journal, 314 (March 30, 1855).

69. Woolley, Journal, 343 (May 13, 1855); Centreville, Delaware, Branch Records, 9.

70. Woolley, Journal, 345 (May 18, 1855).

71. Woolley, Journal, 346 (May 21, 1855).

72. Woolley, Journal, 382 (July 4, 1855).

73. Woolley, Journal, 435 (September 27, 1855). See Matthew 25:40 and Mark 9:41.

74. Wooley, Journal, 439–40 (October 1855).

75. Woolley, Journal, 439–40 (October 1855). See Luke 10:37.

76. Arlene Kaplan Daniels, “Invisible Work,” Social Problems 34, no. 5 (December 1987) 403–15, https://doi.org/10.2307/800538.

77. “Liverpool to Philadelphia, 27 Feb 1855–20 Apr 1855,” Saints by Sea, Latter-day Saint Immigration to America, accessed December 5, 2023, https://saintsbysea.lib.byu.edu/mii/voyage/333; “Liverpool to Philadelphia, 31 Mar 1855–5 May 1855,” https://saintsbysea.lib.byu.edu/mii/voyage/205; “Liverpool to New York, 26 Apr 1855–27 May 1855,” https://saintsbysea.lib.byu.edu/mii/voyage/432; “Liverpool to Philadelphia, 17 Apr 1855–21 May 1855,” https://saintsbysea.lib.byu.edu/mii/voyage/81.

78. Fred E. Woods, “A Gifted Gentleman in Perpetual Motion: John Taylor as an Emigration Agent,” in John Taylor: Champion of Liberty, ed. Mary Jane Woodger (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2009), 175–84.

79. The immigrants arrived on four ships, beginning with the Siddons (April 20, 1855; see Woolley, Journal, 330 [April 24, 1855]); Juventa (May 5, 1855; see Woolley, Journal, 339 [May 7, 1855]); Chimborazo (May 21, 1855; see Woolley, Journal, 346 [May 1855]), and William Stetson (May 27, 1855; see Woolley Journal, 353 [May 30, 1855]). The names of the ships were identified by arrival date and by matching passenger names with the names of immigrants mentioned in Woolley’s journal.

80. Woolley, Journal, 334 (April 29, 1855).

81. A Dearborn was “a light, four-wheeled vehicle with a top and sometimes side curtains, usually pulled by one horse. Long-standing tradition, dating back to 1821, attributes its design to General Henry Dearborn. It usually had one seat but sometimes as many as two or three, and they often rested on wooden springs.” See “Dearborn Wagon,” Dictionary of American History, Encyclopedia.com, updated November 15, 2023, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/dearborn-wagon.

82. Woolley, Journal, 348 (April 23, 1855).

83. Woolley, Journal, 335 (April 30, 1855).

84. Woolley, Journal, 344 (May 16, 1855).

85. Woolley, Journal, 353 (May 30, 1855).

86. Woolley, Journal, 354 (May 31, 1855). He needed to leave the girl with someone because he was due to pick up another group of immigrants.

87. Woolley, Journal, 349–50 (May 25, 1855).

88. Woolley, Journal, 360 (June 7, 1855).

89. Erastus Snow to Messrs Editors, October 31, 1840.

90. “Jacob Hofheins Company (1857),” Church History Biographical Database, accessed December 7, 2023, https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/chd/organization/pioneer-company/jacob-hofheins-company-1857. Tables showing family relationships available from the author.

- Being Latter-day Saints (1841–1857): Four Matriarchs in the Centreville, Delaware, Branch

- “It Must Needs Be”

- Was Joseph Smith a Money Digger?

- Coming and Going to Zion: An Analysis of Push and Pull Factors Motivating British Latter-day Saint Emigration, 1840–60

- Learning Eternal Truths in Joseph and Emma Smith’s Restored Kirtland Home

- Your Daddy or Your Father?—Mimetic Desire versus Christian Fatherhood

- What’s in a Name?: The Growing Focus on Jesus Christ (by Name) since 2000 in General Conference Talks

Articles

- Slavery in Zion: A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847–1862

- Approaching the Tree: Interpreting 1 Nephi 8

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone