Sacred Connections

LDS Pottery in the Native American Southwest

Article

-

By

Richard G. Oman,

Contents

In the fall of 1994, an exhibition, “Sacred Connections, Art and Latter-day Saint Native Americans in the Southwest,” opened at the Museum of Church History and Art. Among the scores of objects on exhibit were eight clay pots that express Latter-day Saint themes. This article examines those pots and attempts to put the pottery into a cultural context. Some of the pots were commissioned by the Museum of Church History and Art; all are in its permanent collection.

Latter-day Saints came into contact with Native Americans in the Southwest in the nineteenth century. In 1858, Jacob Hamblin and a small group of fellow missionaries made their first proselyting expedition to Arizona. Initially, their missionary focus was the Hopi, who inhabited a series of dry, windswept mesa tops in northern Arizona. Eventually some Hopi became Latter-day Saints.

Chief Tuba (or Tuvi in Hopi) presided over a small summer village of Moencopi, located about fifty miles west of the main Hopi villages. After he and his wife joined the Church, they spent several months in the St. George area of southern Utah, where they went through the newly completed and dedicated St. George Temple. In 1873, Tuba invited the Mormons to settle near Moencopi. This settlement, named Tuba City in honor of this Hopi chief, was the first Latter-day Saint settlement in Arizona.1

Since that time the Church has continued to grow among the various tribes of the Southwest, with the largest growth occurring after 1946, when the Church established the Navajo-Zuni Mission (later known as the Southwest Indian Mission) with Ralph Evans as the first mission president. Today there are many LDS chapels, branches, wards, and even a stake among the Southwest Native Americans.2

The Indian Southwest is an area with limited economic resources. Little industry is there other than coal mining and power plants. Low rainfall precludes an extensive agricultural economy. Desert conditions create limits to the livestock-carrying capacity of the fragile ecosystem. Most of the area is distant from any major cities, making urban employment very difficult. Today, one of the most viable economic activities among this people is the arts. Built on cultural and artistic traditions, Native American art is perfectly suited to the limited economic resources of these people because its production requires little or no capital for an artist to begin.

Native American art in the Southwest connects to the land, tribal traditions, the family, and the transcendent spirituality in and through all things. The home is the art school; and the family, the art faculty. The artists use materials that come mostly from the earth. They dig and hand process the clay and use local minerals for dyes, paints, and gemstones. Plants native to the area provide weaving materials for baskets and for some dyes and paints. Sheep provide wool for weaving rugs. The Navajo and Pueblo usually fire their pots in a wood fire, the Hopi use sheep dung, and the Santa Clara use horse dung. The artists’ tools are very basic—simple looms, no potters wheels, and usually no kilns. Most of the basic techniques and the decorative designs and forms have ancient roots that relate to tribal traditions. The visual symbols of this art frequently reflect a spiritual world view.

Some Anglo-Americans find in Native American art an antidote to many of the physical and social pathologies in the dominant American culture. This Anglo interest in acquiring Native American art helps give the most competent of the Southwest Native American artists a ready market for their art. For the artists, this market provides a stimulus to continue to produce art whose original functionality has been eclipsed by mass-produced consumer items. (For example, most Native Americans now use plastic pails instead of large handmade pottery jars for carrying water.) Thus the production of art provides a cottage industry that reinforces cultural roots rather than fragmenting the artists with secularism.

This flourishing contemporary, and yet ancient, Native American art tradition in the Southwest includes many fine Latter-day Saint artists. Their art is rich in religious message, yet the artists frequently express themselves with the visual symbolism of their own cultures. This visual language can be almost as enigmatic to those from a different culture as are unfamiliar verbal symbols.

While we are accustomed to realizing the need for translators in a linguistically diverse Church, we sometimes forget other potential pitfalls in communication. However, once understood, Latter-day Saint art in the Native American Southwest exemplifies spiritual transcendency in a cross-cultural environment. Following is a guide to some of their art pieces, which bond all Latter-day Saints together by celebrating their shared beliefs and spiritual commitments.

Corn Pot by Iris Youvella Nampeyo

Miniature Corn Pot by Charlene Youvella

The elegantly formed Corn Pot (see figure 2a) celebrates corn as a unifying symbol. For the Hopi, corn has deep symbolic meaning. Corn is the Hopi “staff of life.” The seeds for corn were first brought to the Hopi by Corn Maiden, who taught them how to plant the corn and who continues to send the necessary rain for the corn when the Hopi pray diligently.3 When a Hopi prays, he or she sprinkles cornmeal on the ground as a sign of reverence before Deity. One of the Hopi clans is the Corn Clan. Iris Youvella Nampeyo is a member of that clan. She signs her pots with an ear of corn.

Hopi potters usually learn by watching their mothers make pots at the kitchen table. Iris Nampeyo learned to make pots while watching her mother, Fannie Nampeyo Polacca. In turn, Miniature Corn Pot (see figure 2b), made by Charlene Youvella, Iris Nampeyo’s daughter, shows the obvious influence of the maternal model. Such conscious imitation is typical of folk artists, who sink their roots deeply into their tradition and their family to draw strength. Change happens in any art tradition, but it happens much more slowly among the folk arts of traditional societies.

In this sense, folk art is an artistic world view. For example, much of the avant-garde “fine art” tradition of the West awards critical acclaim to innovation and individualism. Artistic energy often comes from fighting against tradition. The folk art celebration of continuity connects the artists and their work to their societies and other generations. This difference in values is one of the great divides between the world views of the folk art tradition and the contemporary western fine art tradition.

My Son, Await the Coming of the Mormon Missionaries by Thomas Polacca

Tom Polacca, the grandfather of the artist, was an early Latter-day Saint convert among the Hopi. This remarkable man spoke several languages, was the leader of the Corn Clan, founded a trading post at the foot of First Mesa, established a post office and a school nearby, and was one of the principle Hopi informants for the Smithsonian ethnographer, Walter Jesse Fewkes (1850–1930), in documenting Hopi traditions and ceremonies. A town grew up around his trading post and was named Polacca, Arizona, in his honor. This pot represents the spiritual legacy of Tom Polacca and his family.

When Polacca was an old man, he called his children around him to tell them about his faith. He bore his testimony of the gospel and told his children that someday the Mormons would return with the book that told the story of their people. He made them promise that they would not join any other Christian church, but would wait for the Mormons.

On the pot (see figure 3), Tom Polacca is the man praying. A feather, the Hopi symbol for prayer, is coming from his mouth. The stylized eagle above him represents the Holy Ghost, and the figure behind him represents his guardian spirit. The Book of Mormon and the Bible are shown because they are the spiritual guides for life. The hills and tree represent the Polacca family ranch, where Tom gave the speech to his family and where Mormon missionaries eventually came to baptize his descendants. The tree also represents the Tree of Life. The footprints represent the visits of President Spencer W. Kimball to the ranch. The stone base with the plaque represents a monument which tells Tom Polacca’s story at his ranch grave site. The great feathered disk represents the sun, the traditional Hopi symbol for the Lord,4 who smiles down on this historical experience.5

My Testimony Pot by Gary Polacca

My Testimony Pot (see figure 4) gives Gary Polacca’s personal interpretation of part of the Hopi migration pattern, a traditional pattern that has been used by generations of artists in the Polacca family. Migration is an important aspect of Hopi cosmology and history. The Hopi believe that they lived in worlds previous to this one and that they will go to other worlds after they die. They also have a tradition that they migrated across water and then traveled north to their present homelands on the tops of the windswept mesas of northern Arizona.6

The kneeling figure is the brother of Jared holding stones in a basket. The Lord (depicted in the traditional Hopi deity symbol of the sun) reaches out his finger to touch the stones to give them light for the Jaredite barges. The barges are entered from the top with a kiva ladder. The numerous figure groups are migrating people; the footprints represent their migration. The two-story buildings link this migration to Polacca’s own Hopi people.7

The next major figure is Nephi holding the sword of Laban. Above him are feathers representing the communication of the Lord ordering Nephi to slay Laban to obtain the plates of brass. Nephi’s family needed these records before they set out on a migration to the promised land.8

Gary Polacca is the son of Thomas Polacca. The family continuity in art is readily apparent in the similarity of style of their two pots.

Three Degrees of Glory Pot by Les Namingha

The artist, Les Namingha, served a mission to England and graduated from Brigham Young University. He is a cousin of the Polaccas and the Youvellas, all of whom descend from the great Hopi potter Nampeyo.9 But Namingha grew up in Zuni, a Pueblo neighboring the Hopi. This pot (see figure 5) shows the influence of both Hopi and Zuni cultures. The form, technique, materials, and style are Hopi, but some of the iconography is Zuni.

The sun, moon, and stars represent the three degrees of glory. The small faces with rays represent the inhabitants of those kingdoms. The expressions on the faces and the amount of light in their rays reflect the level of glory. The form of these faces was derived from ancient Zuni kiva murals familiar to the artist. In the center is a depiction of Christ standing on an altar. His face is covered because Namingha felt that the face of Christ was too sacred for him to depict.10

Echoes of the Ancient Ones by Lucy Leuppe McKelvey

After growing up on the Navajo Reservation, Lucy McKelvey served a mission and graduated from Brigham Young University. While she was a college student, she became friends with a Hopi man and visited his family in Arizona. His mother was a potter and shared her knowledge of Hopi pottery techniques with McKelvey. These circumstances are significant for two reasons: (1) Traditional Hopi pottery techniques are much more refined than traditional Navajo techniques. By incorporating Hopi techniques into her pottery, McKelvey was able to create far more sophisticated and complex works of art than she might have otherwise. (2) The Hopi and the Navajo have been battling about land rights for several decades. As a result, the feelings between these two tribes are at best very cool and frequently hostile. For McKelvey, the Church and BYU provided environments that bridged these ancient hostilities. The result is the development of a new tradition in Navajo art that combines Hopi technique and largely Navajo forms and symbols.

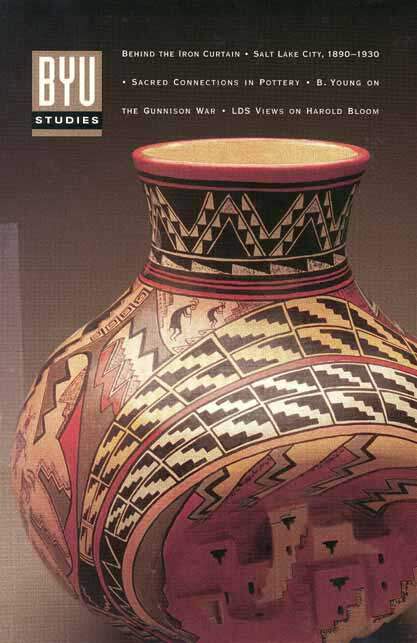

This pot (see front cover and figure 1) represents McKelvey’s feelings about the Book of Mormon, which she expresses in symbolic elements drawn mostly from the native peoples of the Southwest. The migration to the promised land is represented by four Mimbres figures11 symbolizing Laman, Lemuel, Nephi, and Sam. The figures cross the waters on whirling logs such as those depicted in the Nightway Chant.12 The promised land is shown by the four sacred mountains that mark the traditional home of the Navajo—Hesperus Peak (the north mountain), Mount Taylor (the south mountain), Blanca Peak (the east mountain), and the San Francisco Peaks (the west mountain). In the center are the gold plates from which the Book of Mormon came. Radiating from these are step patterns that are the Navajo symbol for rain clouds; in the arid Southwest, rain is an expression of heavenly blessings.

Below the plates is an Avanju, or plumed water serpent. This plumed serpent represents the traditional god of the Santa Clara Pueblo—the god that taught farming and was the arbiter of morals. The Avanju is the equivalent of Quetzalcoatl of Meso-America.13 The imagery of the water serpent also brings an association with the blessings of rain and life.

On the other side of the pot is a deep indentation with a bas relief of Mesa Verde–like structures, which echo the ancient ones as does the Book of Mormon. Uniting these structures as well as the forms on the opposite side of the pot are swirling rain clouds representing blessings from the Lord.

Whirling Rainbow Goddesses Pot by Lucy Leuppe McKelvey

Whirling Rainbow Goddesses Pot (see figure 6) is a moral diagram. Navajos have a spiritual concept known as hozho, which combines aesthetic and moral principles. The most general definition of hozho is “beauty.” But beauty in this context includes good health, long life, reverence for the aged, and an imperative to radiate and create harmony. Above all else, hozho implies being self-controlled, spiritually centered, and dynamically active in hard work.14

The form and pattern on this pot are perfectly symmetrical, reflecting self-control and spiritual centeredness. The curvature of the forms express energy and movement. The rainbow figures represent the blessings from the heavens (rain seems to be the universal metaphor for blessings in arid climates) that come from being spiritually centered and dynamic. The plants represent the direct benefits of these heavenly blessings. Thus, this aesthetic system brings with it a moral imperative of how we should live our lives. It also combines the symmetry of the Renaissance and the dynamics of the Baroque—no small contribution to the history of world art.

Plan of Salvation Pot by Shirley Benn

Shirley Benn is also part of the “royal family” of Hopi potters. Her great grandmother was Nampeyo, and her mother is Daisy Hooee. Fannie Nampeyo Polacca, Thomas and Gary Polacca, and Iris Youvella are her cousins. Les Namingha is her nephew.

As a young woman, Shirley Benn joined the Church but eventually became inactive. A few years ago, her son died tragically, throwing Benn into deep depression and longing. She began looking for ultimate answers about life. This search led Benn and her husband, Virgil, back to the Church. In the Benns’ search, the plan of salvation was the most powerful element. When I approached Benn about doing a pot for the Museum, she said she wanted to create one that depicted the plan of salvation. I initially tried to dissuade her from that theme, thinking it was too monumental to depict on a single piece of pottery, but she insisted that this was the theme that reflected her deepest spiritual experience. She has chosen to depict this sacred plan using mostly traditional Hopi imagery.

The first image (see figure 7) shows the Lord, dressed as a Hopi priest, playing a flute that calls forth his spirit children and sending them through the veil into this mortal life. The next scene shows the hand of the Lord creating this world with animals (a stylized parrot); the sun; plants; and the blessings of rain, depicted by a rainbow arching over the beans. Veils bracket the next image, death, which is portrayed as a huge beetle.

Following the death image, the spirit world is represented by a maze pattern showing the further-searching path. After the next veil is a Hopi sash with step patterns that go up and down. Benn explains that this section represents the possibilities for those that did not have the opportunity to hear the gospel in this life. Their willingness to embrace the gospel in the spirit world determines whether they advance up the steps or go down.

The final panel depicts the Resurrection, the Judgment, and the assignment to degrees of glory. Michael, the archangel, is blowing his trumpet and shaking a rattle to call forth the dead from their graves. The Lord, represented only by his hand, is sending his children to the three degrees of glory. The final vertical band is dark; it is the journey to outer darkness, represented by the bottom half of the pot. The contrast between the kingdom of light and the kingdom of darkness is represented in the vertical bifurcation of the pot.

Lehi’s Vision of the Tree of Life by Harrison Begay Jr.

Of all the pots depicted in this article, Lehi’s Vision of the Tree of Life (see figure 8) is the most straightforward in its symbolism. The artist shows male and female figures, dressed in traditional clothing of the Southwest, holding onto the iron rod, which represents the word of God. Below them are waves of the filthy stream, which represent the depths of hell. At the end of the rod is the tree of life with its bright fruit representing the love of God. The style and composition of the pot combine with economy of form and jewel-like perfection to make a statement that is powerful in its simplicity.

Harrison Begay’s development as a potter has some similarities with the evolution of Lucy McKelvey’s art. Begay is also a Navajo, whose tribe has no carved blackware pottery tradition. While on his mission, Begay was given special assignments to create paintings about missionary work. He met his wife, a Santa Clara Pueblo, while attending school in Provo. Most of the Indian tribes in the Southwest are matriarchal, which means that when a couple is married they go to live with the wife’s people. When Begay moved to Santa Clara Pueblo, he learned pottery making from his wife’s family.15

Santa Clara pottery is completely hand formed and carved. It is then polished with a smooth stone to give it a lustrous finish. Where a matte finish is desired as part of the design, it is left unpolished. Afterwards, the pot is fired in a wood fire. When the fire has burned down to coals, it is smothered with powdered horse dung, which causes a reduction atmosphere. The fire then sucks the oxygen out of the clay and replaces it with carbon, changing the natural redware to black.

Because Begay’s Navajo tradition was different from that of the Santa Clara Pueblo, he was freer to experiment with a variety of forms while using Santa Clara techniques.

Lehi’s Vision of the Tree of Life by Tammy Garcia

Like most traditional artists in the Southwest, Tammy Garcia learned pottery making from her family. She comes from a long line of distinguished Santa Clara Pueblo potters, including two of the most prominent, Margaret Tafoya16 and Terrisita Naranjo.17 Garcia digs her clay from the hills near Santa Clara, cleans the clay, and mixes it with the temper of volcanic ash also obtained from the area. She and her husband, Leroy (who runs an art gallery), live in Taos near the pueblo of his family.18 Garcia has won virtually every award possible from the various Native American art competitions in the Southwest.19 Her work is included in the collections of the Museum of the American Indian in New York City and the Heard Museum in Phoenix.20

Garcia is known for three distinctive aspects in her art: (1) She makes very large pots completely by hand with no potter’s wheel and fires them without the use of a kiln. Very few Pueblo potters attempt such large pots using these primitive techniques because several month’s work can be lost in an instant if the pot breaks in firing. (2) She uses design elements from many Native American sources in the Southwest in addition to the Santa Clara Pueblo. This openness to new forms made it much easier for her to create a pot as symbolically demanding as the one depicting Lehi’s Vision. (3) Garcia carves a much larger proportion of the pot than is usually done by Santa Clara potters. This technique gives her a more expansive field upon which to depict a complex story.

The symbolism of Lehi’s vision is quite obvious, but two design elements stand out (see figure 9 and back cover). The path and the iron rod are dramatically highlighted by a light-cream slip. The great and spacious building is represented by basic pueblo architecture. This second aspect seems to follow Nephi’s admonition, “I did liken all scriptures unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning” (1 Ne. 19:23).

Conclusion

As we look at the growth of the Church around the world, it is the non-Anglo cultures that are experiencing the most dramatic growth curves. Since art is a direct way of understanding peoples and cultures, it behooves us to look carefully at the art of these new Latter-day Saints in order to gain a greater understanding and appreciation of what is rapidly becoming the future majority membership of the Church.

In addition, the study of these eight pots from Native Americans in the Southwest can expand our understanding of contemporary religious art in several ways. Significant art is not limited to oil painting or bronze and marble sculpture. Art can be linked intimately with the land. The home and family can be an art studio and school. Art can draw upon rich visual symbolism when it is rooted in an ancient artistic tradition. Art can be a significant connection between many generations of a family rather than becoming a cultural fracture line. Art can also cross cultural boundaries and still maintain its artistic integrity. Art and the Church can facilitate a peaceful bonding among peoples that are normally at odds with each other. There is more to artistic significance than innovation for the sake of innovation. However, when innovations do develop within an artistic tradition, that art can still remain connected with tradition through the continuity of techniques, materials, forms, and iconography. In the midst of modern breakneck changes, some of the contributions of such art are continuity, connectedness, and spiritual values.

About the author(s)

Richard G. Oman is Senior Curator, Museum of Church History and Art, Salt Lake City.

Notes

1. This LDS settlement continued until the early 1900s, when it was incorporated into the Navajo Reservation by the federal government. For the extension of the Navajo Indian Reservation, see United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, Correspondence, 1902–1903, letters relating to the purchase by the federal government of claims of settlers around Tuba City, Arizona; photocopies courtesy of Ralph Evans, Archives Division, Historical Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City (hereafter cited as LDS Church Archives). Three general, but useful, books on early Mormon contact with Native Americans in Arizona and the Southwest are Charles S. Peterson, Take Up Your Mission: Mormon Colonizing along the Little Colorado River, 1870–1900 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1973); Pearson H. Corbett, Jacob Hamblin: The Peacemaker (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1952); and Helen Bay Gibbons, Saint and Savage (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1965). The most concise source on this subject is David Kay Flake, A History of Mormon Missionary Work with the Hopi, Navajo and Zuni Indians (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1965).

2. David Kay Flake, History of Southwest Indian Mission (n.p., 1965), photocopy, LDS Church Archives. This manuscript is a useful reference, particularly for the post–World War II period.

3. Howela Polacca, “The Hopi Corn Maiden,” as told to Lucy Bloomfield, 1936, typescript, LDS Church Archives.

4. The scriptures frequently use symbolism to communicate feeling as well as physical description. The symbolism of the sun as the Lord is not without precedent in sacred writ. Modern revelation teaches that the “fire” of the Second Coming is the actual presence of the Savior—a celestial glory comparable to the sun (D&C 76:70). The prophet Joseph Smith saw the Father and the Son in a pillar of light that was “above the brightness of the sun” (JS—H 1:15–17). When the Savior was transfigured before Peter, James, and John on the Mount of Transfiguration, “his face did shine as the sun, and his raiment was white as the light” (Matt. 17:2). Psalms 84:11 states, “For the Lord God is a sun and a shield.” In Malachi we learn, “But unto you that fear my name shall the Sun of righteousness arise with healing in his wings” (Mal. 4:2). In describing the Lord, Revelation tells us that “his countenance was as the sun shineth” (Rev. 1:16).

5. Museum Acquisition Record Form, October 18, 1990, Museum of Church History and Art, Salt Lake City.

6. Gary Polacca, conversation with the author, Polacca, Arizona, August 23, 1994.

7. Museum Acquisition Record Form, Museum of Church History and Art; and Polacca, conversation.

8. Museum Acquisition Record Form, Museum of Church History and Art; and Polacca, conversation.

9. Nampeyo was the half-sister of early Mormon convert, Tom Polacca. In the late nineteenth century, factory-made containers had almost displaced traditional Hopi pottery as utilitarian containers. The few remaining Hopi potters had nearly lost the traditional tribal style; most Hopi potters were doing pale imitations of Zuni pottery. In 1895, Walter Jesse Fewkes hired Nampeyo’s husband, Lesou, to help in the excavation of a sixteenth-century ruin. Lesou occasionally showed his wife some of the pots and potsherds that he was digging up. Nampeyo began incorporating some of the old patterns into her pots. Her brother Tom and traders in the area began selling her pots to tourists and art collectors. This combination of ancient forms and expanded markets for the pottery created a renaissance in Hopi pottery. Nampeyo taught her children to make pots, and the skill was passed down through the family. The Nampeyo family (they frequently take the name of their esteemed ancestor) have become the most significant family of Hopi potters. To claim descent from Nampeyo is to claim the tradition of the Hopi pottery renaissance. Harry Clebourne James, Pages from Hopi History (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1974); and Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, Seven Families in Pueblo Pottery (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1975).

10. Museum Acquisition Record Form; and Les Namingha, conversation with the author, Polacca, Arizona, September 19, 1994.

11. The Mimbres were agricultural peoples that flourished in southwest New Mexico between A.D. 1000 and 1250. An essential and completely unique aspect of Mimbres pottery painting is its representational character. About one quarter of existing Mimbres pottery paintings—almost two thousand examples—carry images of animals, humans, and objects, all of which are often shown in narrative interaction. See J. J. Brody, ed., Mimbres Pottery: Ancient Art of the American Southwest (New York: Hudson Hills in association with the American Federation of Arts, 1983).

12. The traditional Navajo use their sacred history as part of their healing rituals. A person who is sick is assumed to be out of balance. To restore balance, the patient must make his or her life parallel with the ancient sacred hero figures of the past. This alignment is accomplished by a chant or “sing”—a story from sacred history told through sung poetry. The chant is accompanied by a symbolic sand painting that visually tells the same complex story and takes several days to perform. Much of Navajo sacred history is preserved and regularly used in this way. The Nightway Chant or Sing is one of the stories used as a healing ritual.

13. Betty LeFree, Santa Clara Pottery Today (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1975), 94.

14. For example, an elderly person of good character but bent and wrinkled would have hozho. This person would be seen as beautiful in the Navajo society. On the meaning of hozho and its relationship to Navajo art, see Gary Witherspoon, Language and Art in the Navajo Universe (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1977).

15. Harrison Begay Jr., conversations with the author, Santa Clara, New Mexico, 1985–1995.

16. Gallery 10, Inc., Tammy Garcia (Scottsdale, Ariz.: n.p., n.d.), brochure.

17. Tammy Garcia, conversation with the author, Taos, New Mexico, April 10, 1995.

18. Gallery 10, Inc., Tammy Garcia.

19. Ron McCoy, “The Youthful Age-Old Pottery of Tammy Garcia” Southwest Profile 16, no. 1 (February/March 1993): 33–35.

20. Garcia, conversation.

- Cooperation, Conflict, and Compromise: Women, Men, and the Environment in Salt Lake City, 1890–1930

- Behind the Iron Curtain: Recollections of Latter-day Saints in East Germany, 1945–1989

- Whither Mormon Drama?: Look First to a Theatre

- Sacred Connections: LDS Pottery in the Native American Southwest

Articles

- Father, Forgive Us

- The Great Bean-Count Schism

Creative Art

- Advice on Correct Astronomy

- Cutting the Last Hay

- Old Language

- Ravens at Island in the Sky, Canyonlands, Utah

- When You See Me

- resurrection day in Tallahassee

- Altarpiece

- Beginning with the Keynote Address on Metaphor and Ideology

- The Revelation

Poetry

- Four LDS Views on Harold Bloom: A Roundtable

- Two books on American culture

- My Best for the Kingdom: History and Autobiography of John Lowe Butler, a Mormon Frontiersman

- The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886-1903

- Kidnapped from That Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists

- The Ritualization of Mormon History and Other Essays

- The Allegory of the Olive Tree: The Olive, the Bible, and Jacob 5

- A Storyteller in Zion: Essays and Speeches by Orson Scott Card

Reviews

- Rocky Mountain Divide: Selling and Saving the West

- Special issue on homosexuality, AMCAP Journal

- Two books on emigrant trails

- Behold the Messiah: New Testament Insights from Latter-day Revelation

- Leadership and the New Science: Learning about Organization from an Orderly Universe

- Tolerance: Principles, Practices, Obstacles, Limits

Book Notices

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X