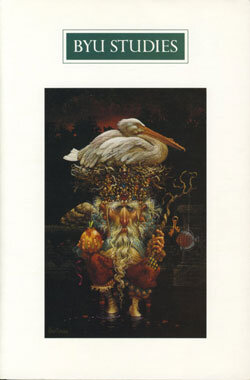

Winged Words

A Portfolio of Paintings and Drawings by James C. Christensen

Article

Contents

Sisters is a painting that draws an audience. Two women face each other in striking profile. The clothing and jewels one wears indicate comfort and riches; the second’s indicate poverty with a gown of similar style but with coarse material long worn to tatters. Yet both faces are identical. Are they biological sisters? Are they sisters whose bond is the shared link of womankind? Are they sisters in spirit? Despite their differences, are they, in fact, equal? The art conceals and reveals.

Sisters, a recent painting by BYU faculty artist James C. Christensen, is part of a series of new works he displayed in a late autumn one-man show in both Utah and Connecticut. Sisters, as well as the other art in the show, could be peeled, layer by layer, to reveal deeper symbols and intentions. The same could be said of Christensen, whose career has expanded beyond the corners of the university and the Intermountain West to interested galleries and audiences on the East and West coasts.

“My own metamorphosis in Sisters came as I painted it,” says Christensen. “I first thought the poor woman would be virtuous and the rich one elitist. But I realized most people I knew were closer to the rich lady’s side—and most were fine, good people. I almost slid into the common falsehood of assigning intrinsic virtue to poverty and inherent evil in having the goods of this world.” He chose instead to have both women serve the best way they could. The poor lady has a white violet, the symbol of hope and faith; the other, a strawberry, also humble, but a representation of the fruitful man. “The lady with money has the ability to do more good works—and because of her means she ought to—yet her strawberry is not quite ripe; maybe there is more for her to figure out.”

There is, no doubt, more to be discovered in all of Christensen’s art, but Christensen prefers to leave most of the understanding to the viewer, believing “there is so much more to a painting if you have to find it.” Vern Swanson, director of the Springville Museum of Art, feels that “Jim’s art gives us room to interpret. We can jump in, but we’ll discover we have a long journey to find the end in his work.”

Christensen’s art has the advantage of significant popular success. People like it. Willing audiences see his shows. In the early 1980s, he provided several paintings for Time-Life Books’ “Enchanted World” series. In 1984, NASA featured Low Tech, Christensen’s lighthearted tribute to space exploring barnstormers, for its twenty-fifth anniversary exhibition, “Visions of Other Worlds.” The Folger Shakespeare Memorial Library in Washington, D.C., offers a Christensen poster that is a montage of the bard’s plays and characters. Since 1985 the Greenwich Workshop in Trumbull, Connecticut, has used Christensen as its only fantasy painter among a stable of acclaimed artists that includes Americana specialist Charles Wysocki, creative wildlife artist Bev Doolittle, and western artist Tom Lovell. Christensen has managed these assignments and others while teaching full-time at BYU.

Christensen’s work is usually finely, even elaborately, detailed using a style focused on clarity of subject, form, color, and detail. He has worked as a commercial illustrator, but his work transcends illustration. “When I began taking fantasy work seriously, I used it primarily as illustration,” he says. “I painted the pictures in my mind that grow as I read people’s books. These paintings communicated everything immediately—usually a necessity in the commercial book market. Now, however, the ‘fantasies’ are my own and my choices are more symbolic. I’m using metaphors and fantasy parables to tell stories that will reach, inform, enlighten, and even amuse.”

Often, for example, he uses fish in his work, symbols of profound life. He’ll follow the idea of fishing as a way to extract the unconscious elements from deep sources, “elusive treasure, legend—or wisdom.”

Christensen propels himself in new directions to keep his art fresh to himself. He challenges his technical expertise, for example, by moving from acrylic to oil, changing his scale, or working in a more abstruse way. He thinks of himself as “a player in the scene of contemporary art . . . but not on the cutting edge of mainstream artists.” By this he means he is not trying for a New York show to establish a reputation. “Being represented by galleries on both coasts doesn’t ‘count.’ Only New York ‘counts,’ and then only in a narrow geographic area where a group of critics and recognized galleries meet to identify and direct contemporary art movements. New movements seem to evolve every year-and-a-half. I don’t want to play that game because a lot of it is not valid. Many New York artists seem to have traded their souls for good public relations, losing the passion or belief that drives them.”

He’ll be an art school of one, if necessary, and said, “If I am ever identified with the mainstream culture, it’s because the culture has moved toward fantasy.” It appears the culture is moving that way.

[*** graphic omitted ***]

Sisters

acrylic

[*** graphic omitted ***]

Benediction

oil

[*** graphic omitted ***]

La Duquesa

oil

[*** graphic omitted ***]

Annunciation

oil

[*** graphics of sketches omitted ***]

About the author(s)

James C. Christensen is an associate professor of art at Brigham Young University.

Charlene R. Winters is fine arts editor for Brigham Young University Public Communications.

Notes

- Chattanooga’s Southern Star: Mormon Window on the South, 1898–1900

- BYU Student Life in the Twenties

- Winged Words: A Portfolio of Paintings and Drawings by James C. Christensen

- Education, Moral Values, and Democracy: Lessons from the German Experience

- Joseph Smith, the Constitution, and Individual Liberties

- The Development of the Doctrine of Preexistence, 1830–1844

Articles

- Beyond “Jack Fiction”: Recent Achievement in the Mormon Novel: A Review Essay

- David Matthew Kennedy: Banker, Statesman, Churchman

- Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition

- Sanpete Scenes: A Guide to Utah’s Heart

- From Acorn to Oak Tree: A Personal History of the Establishment and First Quarter Development of the South American Missions

- Our Latter-Day Hymns: The Stories and the Messages

- The Call of Zion: The Story of the First Welsh Mormon Emigration

Reviews

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone

Lincoln

Print ISSN: 2837-0031

Online ISSN: 2837-004X