The Spectrum of Faith in Victorian Literature

Article

-

By

Bruce B. Clark,

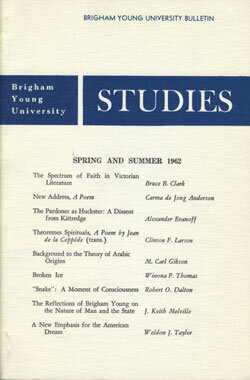

Contents

Unlike that of the Romantic Age preceding Victorianism, and of the Neo-classic Age preceding Romanticism, the literature of the Victorian Age—that is, English literature of the middle and later nineteenth century—is characterized, not by unity but by diversity, not by basic harmony in tone and philosophy but by basic contradiction. On the surface this was an age of solidarity and even stuffy placidity, with its triumph as well as its tragedy arising from an over-confidence in things material. But underneath it was an age of turbulence and of ideological revolution. In this age Darwin and his associates were challenging man’s traditional confidence in a God-created, God-controlled universe; and on a different scientific front Marx and his associates were propounding theories that would prove equally shattering to western man’s traditional faith in divine teleology as well as to the economic structure of his comfortable world. In this age the great labor unions began their climb to power, and Freud with all his impact on life and literature was emerging on the horizon. The Victorian Age began in early nineteenth century romantic idealism and ended a little over a half century later in modern naturalistic pessimism. And the greatest ideological issue of the age was faith versus doubt, with the latter seeming to emerge unsteadily triumphant. Hence the appropriateness of the most famous figure of speech in nineteenth century poetry: Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” description in 1867 of the Sea of Faith, which had once encircled the earth so securely, as retreating with a melancholy and fading echo of withdrawal.

Significantly, in Victorian literature not only do we find a general heterogeneity and complexity of tone and philosophy, but we can identify in major works of literature of the period clear expressions of all four of the basic and contradictory religious positions which human beings may hold: liberalism, fundamentalism, humanism, and existentialism.1 To see and feel these positions in conflict as voiced by the great writers of the era, a surging ideological tug of war for dominance, is one of the rewards of exploring Victorian literature.

Liberalism. Liberalism is “the conjunction of proximate optimism with ultimate optimism.” It is affirmative and optimistic with regard to man not only in this life but also in a life after death. “Its theology defines man as good rather than evil, or at least as morally neutral with a high potentiality for goodness.” It affirms that man, both as an individual and collectively as part of the social group, is “inherently capable of achieving an abundant and happy life,” especially as aided and guided by God, his creator. In mortal life happiness and goodness are richly attainable, and beyond death the promise is even more glowing. “For man is an immortal soul, God is real, and man’s destiny is an eternal beatitude in communion with his divine creator.”2

As the spokesman of liberalism one might choose Tennyson if his voice were not so sentimentally plaintive as he endeavors to make peace with his troubled soul and as he stretches “lame hands of faith”3 and “hopes” (rather than knows or even firmly believes) that he will meet his Maker face to face.4 A better choice would be Thomas Carlyle, that impassioned Victorian prophet who cried out against the growing materialistic atheism of his age and vigorously asserted his faith that man and the universe are “sky-woven” creations of God and that “the fearful unbelief is unbelief in yourself.”5 And the best choice is Robert Browning (1812–1889), that robust optimist whose total affirmation of life here and hereafter makes him an ideal spokesman for liberalism. That he now seems not only the greatest poet of his generation but possibly also the greatest English poet since Milton is not central to the subject of this essay but is a point worth noting in passing.

Optimists are usually either so insensitively worldly or so sentimentally unworldly that they are offensive, and especially so in literature; but Browning’s optimism is vigorously attractive even to those who may not share it. Strangely, his most widely known statement of optimism, “God’s in his heaven—All’s right with the world,”6 is an extreme and unrealistic view that Browning himself scorned. He put the words into the mouth of a naive little girl, and to ascribe the point of view as Browning’s own would be as wrong as to identify Browning with the hypocritically self-righteous Johannes Agricola or the debased Caliban. Nevertheless, Browning does firmly believe that God is in heaven controlling the universe and that, while much is wrong with the world, the potentiality of man in this life is great and the confidence with which he can look forward to life beyond death is equally great. Occasionally Browning speaks directly of himself and his views, as in the “Epilogue to Asolando” when he describes himself as

One who never turned his back but marched breast forward,

Never doubted clouds would break,

Never dreamed, though right were worsted, wrong would triumph,

Held we fall to rise, are baffled to fight better,

Sleep to wake.

Or as in “Prospice” when with unwavering assurance he looks through death to a reunion with his beloved wife:

I was ever a fighter, so—one fight more,

The best and the last!

I would hate that death bandaged my eyes, and forbore,

And bade me creep past.

No! let me taste the whole of it, fare like my peers,

The heroes of old,

Bear the brunt, in a minute pay glad life’s arrears

Of pain, darkness, and cold.

For sudden the worst turns the best to the brave,

The black minute’s at end,

And the elements’ rage, the fiend-voices that rave,

Shall dwindle, shall blend,

Shall change, shall become first a peace out of pain,

Then a light, then thy breast,

O thou soul of my soul! I shall clasp thee again,

And with God be the rest!

At other times Browning speaks his views not directly but through the words of one of his characters, as when the worldly but exuberantly likable Fra Lippo Lippi says,

This world’s no blot for us,

Nor blank; it means intensely, and means good.

And earlier says, referring to his purpose in painting,

If you get simple beauty and nought else,

You get about the best thing God invents.

Browning also speaks through Rabbi Ben Ezra—of his confidence that life is good all the way, even into old age:

Grow old along with me!

The best is yet to be,

The last of life, for which the first was made.

Our times are in his hand

Who saith, “A whole I planned;

Youth shows but half. Trust God; see all, nor be afraid!”

Of his assurance that man is divinely created and, at his best, divinely motivated to unselfishness:

Rejoice we are allied

To that which doth provide

And not partake, effect and not receive!

A spark disturbs our clod;

Nearer we hold of God

Who gives, than of his tribes that take, I must believe.

Of his belief in the God-like potentiality of man:

Therefore I summon age

To grant youth’s heritage,

Life’s struggle having so far reached its term.

Thence shall I pass, approved

A man, for aye removed

From the developed brute—a god, though in the germ.

And of his conviction that mortal existence is a divinely planned phase of progressive immortality for each human being:

Aye, note that Potter’s wheel,

That metaphor! and feel

Why time spins fast, why passive lies our clay —

Thou, to whom fools propound,

When the wine makes its round,

“Since life fleets, all is change; the Past gone, seize today!”

Fool! All that is, at all,

Lasts ever, past recall;

Earth changes, but thy soul and God stand sure.

What entered into thee,

That was, is, and shall be.

Time’s wheel runs back or stops; Potter and clay endure.

We feel Browning’s vigorous affirmation of life especially in the several poems that develop his doctrine of “success in failure,” the “philosophy of the imperfect”—that man should direct all his energy toward achieving high goals, even impossibly high goals, for to set low goals and achieve them is to fail whereas to set high goals and strive unceasingly toward them is to succeed even though the goals may not be fully reached. Browning would on this point agree with the pathetic Andrea del Sarto, who broodingly acknowledges that “a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for?” And even more explicitly the pall-bearer in “A Grammarian’s Funeral” expresses Browning’s philosophy when he says,

That low man seeks a little thing to do,

Sees it and does it;

This high man, with a great thing to pursue,

Dies ere he knows it.

That low man goes on adding one to one,

His hundred’s soon hit;

This high man, aiming at a million,

Misses an unit.

That, has the world here—should he need the next,

Let the world mind him!

This, throws himself on God, and unperplexed

Seeking shall find him.

Many times elsewhere Browning communicates his strong spiritual affirmativeness to us, as in the great musical soul-study “Saul,” and in “The Epistle of Karshish,” that extraordinary psychological study of the impact of Christ’s mission on a non-believer who, in spite of all his stubborn assertion otherwise, reveals himself as almost a believer.

But even more vividly than when Browning speaks explicitly through himself or through his characters, he ironically communicates his views to us indirectly and upside-down through his unattractive characters. In fact, the bulk of what we know about Browning’s specific views we infer in this manner. We sense his admiration for sincerity and honesty and simple goodness because the proud, jealous Duke of Ferrara in “My Last Duchess” is so arrogantly materialistic, and because the dying Bishop in Saint Praxed’s Church and the soliloquizing monk in the Spanish Cloister are so sensually worldly and (the latter at least) so hypocritically self-righteous. We know that Browning believes man has the responsibility and opportunity, in this life, to work towards his own eternal salvation because the despicable, Johannes Agricola (See “Johannes Agricola in Meditation”) and the degenerate Caliban (See “Caliban Upon Setebos”) believe otherwise, thinking themselves destined to inherit (Johannes) or endure (Caliban) the unalterable whims of an irresponsible God who predestines them to their reward or doom. And we know that Browning believes earthly man should live his daily experiences to the fullest capability in joy and meaning without brooding about the hopes of the past (see “The Last Ride Together”) or procrastinating the desires of the present (see “The Statue and the Bust”) or rationalizing one’s failures (see “Andrea del Sarto”).

Out of and through all his poems Browning emerges not only as a great poet but as the most vigorously optimistic writer of his age—optimistic, that is, about the potentiality of man, both in this life (proximate optimism) and in the life to come (ultimate optimism). He stands as a complete and almost perfect example of and spokesman for religious liberalism.

Fundamentalism. Fundamentalism is “the conjunction of proximate pessimism with ultimate optimism.” Its view of this life is basically negative, but its view of life after death is vibrantly affirmative. It regards man, both individually and collectively, as sinful and helpless. “By nature he is depraved and morally corrupt, his mind and will at enmity with God.” Thus, “without confidence in himself, skeptical of human reason, suspicious of every human effort, and afraid of contamination by the world’s culture, fundamentalist man throws himself upon the mercy of God.” Burdened with original sin and debased by all the influences of earthly environment, man is lost, but in his unworthiness he is redeemed by an omnipotent and merciful God. “Without merit and convicted of utter depravity, he is yet saved and exalted by the free gift of grace.”7

As a representative of fundamentalism a case might be made for Gerard Manley Hopkins, who in “The Leaden Echo” laments the transitoriness of beauty and joy in this life and in “The Golden Echo” asserts that all that is lost in mortality endures permanently in immortality with God; but Hopkins is too vividly descriptive of beauty all around us in the God-created universe to be fully fundamentalistic in point of view. A better case could be made for Francis Thompson, who in his masterpiece, “The Hound of Heaven,” portrays sinful man as, however unworthy, ultimately overcome by the saving grace of an omnipotent, all-merciful God. But the best example of fundamentalism in Victorian literature is Christina Rossetti (1830–1894), that gifted poet8 and anguished Christian burdened not so much by personal sin as by a heritage of sin-consciousness in the human race yet looking forward to redemption through Christ and an after-life of joy and fulfillment.

To understand Christina Rossetti’s religious attitude one needs to know something of her life: that as a girl she was by nature affectionate and even gay, that twice she declined to marry men whom she deeply loved, that increasingly as she grew older she lived as an ascetic recluse, yearning for the beauties and pleasures of the world but deliberately withdrawn from them.

The first man whom Christina Rossetti loved was James Collinson, an earnest young painter of pious habits and not very great talent whom she met when she was seventeen. From the very first they loved each other, and for months they made preparations for marriage; but when the wedding-date drew near, Christina refused to go through with it. Her explanation was that some vacillations by Collinson between Catholicism and Anglicanism made marriage with him impossible, but other reasons more deeply rooted in her religious background seem at work. Religion first drew them together, and now religion held them apart. And Collinson slipped out of her life into obscurity and pathetic memory. Perhaps their romance was doomed from the outset, for even in her earliest poems the theme of love is frequently accompanied by the theme of renunciation, her typical maidens turning from an earthly to a heavenly lover. But whatever the explanation for her actions, there seems little doubt that she sincerely loved Collinson and that, loving him, she rejected him. Her decision caused her months of suffering and probably contributed to her life-long melancholia. But she endured her grief alone. Only in poems, mostly found among her manuscripts after her death, did she write of her broken dreams. When the experience was full upon her, she wrote “Seeking Rest,” which ends,

My Spring will never come again;

My pretty flowers have blown

For the last time; I can but sit

And think and weep alone.

“Mirage,” written when Christina was almost thirty, indicates that after ten years her sense of loss was still acute:

The hope I dreamed of was a dream,

Was but a dream; and now I wake,

Exceeding comfortless, and worn, and old,

For a dream’s sake.

I hang my harp upon a tree,

A weeping willow in a lake;

I hang my silenced harp there, wrung and snapt

For a dream’s sake.

Lie still, lie still, my breaking heart;

My silent heart, lie still and break:

Life, and the world, and mine own self, are changed

For a dream’s sake.

And when she was over forty she wrote the sonnet “Love Lies Bleeding,” certainly in remembrance of Collinson, perhaps after passing him on the street without his recognizing her:

Love, that is dead and buried, yesterday

Out of his grave rose up before my face;

No recognition in his look, no trace

Of memory in his eyes dust-dimmed and grey;

While I, remembering, found no word to say,

But felt my quickened heart leap in its place;

Caught afterglow thrown back from long-set days,

Caught echoes of all music past away.

Was this indeed to meet?—I mind me yet

In youth we met when hope and love were quick,

We parted with hope dead but love alive:

I mind me how we parted then heart-sick,

Remembering, loving, hopeless, weak to strive:—

Was this to meet? Not so, we have not met.

Christina Rossetti’s second love was Charles Bagot Cayley, a shy, myopic, absent-minded person, with a sweet and quaintly unworldly disposition, who entered her heart several years after her refusal of Collinson. Her feeling for Cayley was not as intense as it had been for Collinson, but it was deeper and even more permanent. She loved his gentleness and admired his learning and integrity, this wistful, lonely scholar. His very oddities endeared him to her, as in a thousand timid ways he tried to let her know that he loved her, not realizing that she had long been aware of this. Christina’s affectionate little poem “A Sketch” delightfully shows her devotion to this timid and lovable man:

The blindest buzzard that I know

Does not wear wings to spread and stir;

Nor does my special mole wear fur,

And grub among the roots below:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

My blindest buzzard that I know,

My special mole, when will you see?

Oh no, you must not look at me,

There’s nothing hid for me to show.

I might show facts as plain as day:

But since your eyes are blind, you’d say,

“Where? What?” and turn away.

Between 1862 and 1866 Christina’s love for Cayley reached its climax, though for the rest of his life he remained a wistful figure weaving in and out of her world. William Michael Rossetti, Christina’s brother, says that she loved Cayley “deeply and permanently . . . to the last day of his life . . . and, to the last day of her own, his memory.”9 In 1864 Cayley worked up enough courage to propose, and for the second time Christina refused to marry a man she loved. It was not that she was without passion. “To give, to give . . . I long to pour myself, my soul,” she cried in one of her untitled little poems; “I long for one to stir my deep—for one to search and sift myself, to take myself.” Again the reason Christina gave for refusing marriage was religion. To her devout Anglicanism, Cayley’s gentle agnosticism was as objectionable as Collinson’s vacillating Catholicism had been.

To understand more fully Christina’s rejection of Collinson and Cayley, we need to look into the centuries-old heritage of fundamentalist Christianity which viewed man as in a fallen state, depraved, unworthy, at enmity with God, and bearing the heavy burden or original sin with all its propensities towards daily evil. Christina was torn with conflicting allegiances, for on the one hand she yearned with all the passion of her sensitive nature for love and beauty, and on the other hand the deep convictions of her family tradition persuaded her that all desires of the flesh are evil, to be subdued, and that even beauty is suspect. The proper course of religious devotion would compel a renunciation of earthly love and a dedication of oneself to God. For a time Christina thought of following her sister Maria into an Anglican Sisterhood, but she chose rather to renounce the world while remaining in it. Two sonnet sequences—Monna Innominata: A Sonnet of Sonnets (14 sonnets) and Later Life: A Double Sonnet of Sonnets (28 sonnets)—reflect fully Christina’s renunciation of the earth and its fulfilling pleasures and record specifically her devotion to Cayley even while she withdrew from him. Many of the sonnets were written directly to Cayley, as for example number six of Monna Innorninata, which begins:

Trust me, I have not earned your dear rebuke,—

I love, as you would have me, God the most;

Would lose not Him, but you, must one be lost.

Such expressions as this—and there are many in her poems—make clear that Christina’s refusal to marry arose from something very deep in her nature which made her shrink from the yearnings of the flesh. In the actions of her life she seems to have been generally successful in subduing the claims of the flesh, but she seems not to have been so successful in conquering her thoughts. Her desires as a woman were never completely quelled by her piety as a saintly martyr. And the consequence was a terrible sense of guilt and anguish and frustration.

Christina’s great source of comfort was a conviction that, although earthly life is a time of suppression and denial, a joyless struggle against sin, life after death is a time of rich fulfillment when all the joys denied in mortality are bestowed in abundance, including the ecstasy of love. Sonnet 10 of Monna Innominata will represent the dozens of her poems which express this fundamentalist faith in the beauty of life after death as contrasted with the weary struggle of mortal life:

Time flies, hope flags, life plies a wearied wing;

Death following hard on life gains ground apace;

Faith runs with each and rears an eager face,

Outruns the rest, makes light of everything,

Spurns earth, and still finds breath to pray and sing;

While love ahead of all uplifts his praise,

Still asks for grace and still gives thanks for grace,

Content with all day brings and night will bring.

Life wanes; and when love folds his wings above

Tired hope, and less we feel his conscious pulse,

Let us go fall asleep, dear friend, in peace:

A little while, and age and sorrow cease;

A little while, and life reborn annuls

Loss and decay and death, and all is love.

The poems are numerous indicating that for Christina “religion was a hair-shirt”10 and that she spent much of her life striving to make herself more acceptable to God and eschewing the earthly things that naturally gave her pleasure. Note as further typical these lines from “A Better Resurrection”:

My life is like a faded leaf,

My harvest dwindled to a husk;

Truly my life is void and brief

And tedious in the barren dusk;

My life is like a frozen thing,

No bud nor greenness can I see;

Yet rise it shall—the sap of Spring;

O Jesus, rise in me.

Many of these poems are rather commonplace artistically, but occasionally a vivid stanza breaks through to show the anguish of desire denied but not destroyed. For example, “An Apple Gathering” begins:

I plucked pink blossoms from mine apple-tree

And wore them all that evening in my hair;

Then in due season when I went to see,

I found no apples there.

And “De profundis” reads:

Oh, why is heaven built so far,

Oh, why is earth set so remote?

I cannot reach the nearest star

That hangs afloat.I would not care to reach the moon,

One round monotonous of change;

Yet even she repeats her tune

Beyond my range.I never watch the scattered fire

Of stars, or sun’s far-trailing train,

But all my heart is one desire,

And all in vain.For I am bound with fleshly bands,

Joy, beauty, lie beyond my scope;

I strain my heart, I stretch my hands,

And catch at hope.

The most interesting of all Christina Rossetti’s poems, both in artistry of language and in ethical content, is “Goblin Market,” that shimmeringly poetic allegory of temptation, submission, and vicarious redemption; but it is too long and complex for analysis here. More explicit, and still vividly poetic, is “The Convent Threshold” (note the implications of the title), which reads in part:

There’s blood between us, love, my love,

There’s father’s blood, there’s brother’s blood,

And blood’s a bar I cannot pass.

I choose the stairs that mount above,

Stair after golden sky-ward stair,

To city and to sea of glass.

My lily feet are soiled with mud,

With scarlet mud which tells a tale

Of hope that was, of guilt that was,

Of love that shall not yet avail;

Alas, my heart, if I could bare

My heart, this selfsame stain is there.

I seek the sea of glass and fire

To wash the spot, to burn the snare;

Lo, stairs are meant to lift us higher—

Mount with me, mount the kindled stair.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

You sinned with me a pleasant sin;

Repent with me, for I repent.

Woe’s me the lore I must unlearn!

Woe’s me that easy way we went,

So rugged when I would return!

How long until my sleep begin,

How long shall stretch these nights and days?

Surely, clean angels cry, she prays;

She laves her soul with tedious tears;

How long must stretch these years and years?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

For all night long I dreamed of you;

I woke and prayed against my will,

Then slept to dream of you again.

At length I rose and knelt and prayed.

I cannot write the words I said—

My words were slow, my tears were few;

But through the dark my silence spoke

Like thunder. When this morning broke,

My face was pinched, my hair was gray,

And frozen blood was on the sill

Where stifling in my struggle I lay.

Anyone reading these lines unacquainted with Christina Rossetti’s ascetic life would almost certainly interpret them as an anguished confession of a carnal sinner pleading with her lover to join with her in repentance and throw themselves upon the mercy of God. A search of her life, however, has not as yet revealed that Christina really sinned in a way to warrant this tormented confession. Scholars have sometimes concluded, therefore, that the poem is not to be interpreted autobiographically. But is it not possible for a really sensitive woman, torn by subdued desires, to remember the Sermon on the Mount and suffer almost as greatly for sins of thinking as for sins of doing?

“The Convent Threshold” turns in a significantly fundamentalist manner11 away from the anguish of the earthly now toward the glory of the heavenly future:

Your eyes look earthward, mine look up.

I see the far-off city grand,

Beyond the hills a watered land,

Beyond the gulf a gleaming strand

Of mansions where the righteous sup;

Who sleep at ease among their trees,

Or wake to sing a cadenced hymn

With Cherubim and Seraphim.

They bore the Cross, they drained the cup,

Racked, roasted, crushed, wrenched limb from limb,

They the offscouring of the world.

The heaven of starry heavens unfurled,

The sun before their face is dim.

And in the heavenly promise Christina even sees love-fulfillment. “How should I rest in paradise, / Or sit on steps of heaven alone?” she asks, and answers with confident assertion as the poem ends:

Look up, rise up, for far above

Our palms are grown, our place is set;

There we shall meet as once we met,

And love with old familiar love.

Thus we see Christina Rossetti as a nearly perfect example of fundamentalism, viewing this life as essentially a place of sin and denial and unhappiness (proximate pessimism) but looking forward to life after death as a time of beauty and joy and love fulfilled (ultimate optimism).

Humanism. Humanism is “the conjunction of proximate optimism and ultimate pessimism.” Like liberalism, it is strongly affirmative with regard to man in this life and his potentiality for earthly happiness and significance. The humanist is theologically negativistic and ultimately pessimistic, however, for he questions the existence and power of God and he does not believe in human immortality. “For him the proximate world exhausts the whole of reality and existence,” and in this world man is alone to work out his problems or be destroyed by them. But the humanist does not sink into morbid despondency, for he has courage and confidence in his own capacities for earthly joy and attainment. Without the security of a sustaining faith in a power beyond himself, the humanist turns to the human race for a cultivation of the good life. The strength of humanism is its “supreme commitment to reason, its faith in man’s creative intelligence, faith that he has the power to discern, articulate, and solve his problems.” But the optimistic view is limited, and man’s victory is fleeting, for the humanist believes that “the universe is totally indifferent to man and his moral aspiration. Every man must die, and after a brief moment the race will perish, and the drama of mankind will be ended without the slightest trace of memory that it ever began.”12

George Eliot, who as a young woman lost her Christian faith but retained a high sense of ethics and purpose in society, becoming increasingly an advocate of humanity’s seeking the good life, could serve as a representative of humanism. But I have chosen rather to use a combination of Matthew Arnold and Edward Fitzgerald (in The Rubaiyat) as examples. The combination seems better than a single representative because humanism as a concept-of-life movement spreads from altruism to hedonism.13 In Arnold we find altruistic humanism, and in Fitzgerald we find hedonistic humanism.

As a young man Matthew Arnold (1822–1888) hungered to believe in God and a God-controlled universe and individual immortality, but he could find no assuring evidence and after some years of anguished searching became in his mature years an agnostic humanist concerned with the improvement of human society. His poems, most of which he wrote as a young man, tend to be melancholy in tone and to reflect the groping, yearning, questioning, searching attitude of youth. His essays, most of which he wrote as an older man, tend to be dignified in tone and to reflect the reasoned, stabilized wisdom of maturity.

In Arnold’s poetry we are especially impressed by his searching, question-asking, answer-hunting attitude. Because the questions he asks are big and the answers he can arrive at are discomforting, his poetry is shrouded by a melancholy and pessimism too gloomy for humanism. Contrast, for example, Arnold’s pessimistic view of old age in “Growing Old” with Browning’s optimistic view in “Rabbi Ben Ezra.” Note also the negative view of life in Arnold’s “A Question: To Fausta,” where he says,

Dreams dawn and fly, friends smile and die

Like spring flowers;

Our vaunted life is one long funeral.

Men dig graves with bitter tears

For their dead hopes; and all,

Mazed with doubts and sick with fears,

Count the hours.

And in “The Scholar-Gypsy” Arnold speaks of the “strange disease of modern life, / With its sick hurry, its divided aims, / Its heads o’ertaxed, its palsied hearts.” Similarly in “Dover Beach” he describes a world that, although beautiful, is filled with the “turbid ebb and flow of human misery” and which has “really neither joy, nor love, nor light, / Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain.” And on through “Rugby Chapel,” “A Summer Night,” and other poems Arnold describes a beautiful but nevertheless insecure and gloomy world. Although most of his poetry is too unaffirmative to be truly humanistic, at times in it we discover strong leanings toward humanism: in “Dover Beach” and “The Buried Life” he appeals for human understanding in a world of incertitude, in “Pis-Aller” he by implication scorns men who cannot believe in the human race unless they believe in God, in “To a Friend” he appeals to us to “see life steadily and see it whole,” and in “Self-Dependence” he advises:

Resolve to be thyself; and know that he

Who finds himself loses his misery!

If in Arnold’s poetry he is primarily a melancholy searcher for truth that he cannot find, in his essays he is primarily a wise counsel-giver, and thoroughly a humanist. It is not that he has now found satisfying answers to the big questions of his poems. If it were this he would be a liberal or fundamentalist rather than a humanist. Rather it is that, having found no solid answers regarding God and immortality, he ceases to worry about them and turns to human society for fulfillment. Throughout his many essays he is a crusader for culture with responsibility, for propagating “the best that is known and thought in the world.”14 He defines culture as “the love of perfection” motivated by not only a “passion for pure knowledge” but also a “moral and social passion for doing good,” and he adds that “not a having and a resting, but a growing and a becoming, is the character of perfection as culture conceives it.” Moreover, individual perfection is impossible without perfection of the group as the whole of society endeavors to cast off the superficiality of “machinery” and the materialistic worldliness of “Philistinism.”15

This is the social idea; and the men of culture are the true apostles of equality. The great men of culture are those who have had a passion for diffusing, for making prevail, for carrying from one end of society to the other, the best knowledge, the best ideas of their time; who have labored to divest knowledge of all that was harsh, uncouth, difficult, abstract, professional, exclusive; to humanize it, to make it efficient outside the clique of the cultivated and learned, yet still remaining the best knowledge and thought of the time, and a true source, therefore, of sweetness and light.16

In his humanistic essays Arnold does not assert that there is neither God nor immortality; he simply quits brooding about them and turns to human society for achievement in this life. He thus becomes the high priest of twentieth-century agnostic humanism with its emphasis upon the world of human potentiality and its assumption that “supernatural” matters are either untrue or beyond proof.

In Matthew Arnold we find agnostic, altruistic humanism. In Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam we find atheistic (or almost atheistic), hedonistic humanism. Some may question the validity of “assuming” that Edward Fitzgerald (1809–1883) speaks his own views through The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and may argue that the poem, as a translation, reflects only the philosophy of the twelfth-century Persian poet Omar. However, a study of the translation in relation to its source will reveal that it is very “free,” and a study of Fitzgerald’s life and other writings will reveal that he apparently was drawn to the poetry of Omar because the two poets were in many respects kindred spirits in point of view towards life. Therefore, The Rubaiyat seems in large measure to be an expression of Fitzgerald’s philosophy as well as Omar’s. And in any case the whole question is rather pointless because, whether The Rubaiyat expresses Fitzgerald’s ideas or not, it is a major and immensely popular poem of the Victorian Age, and it does reflect hedonistic humanism in the Victorian Age. Two related themes run through The Rubaiyat. One is a serious, somber search for meaning in life and for answers to the age-old questions: From whence came life? Does God exist? Is there life beyond the grave? This search is no less serious or meaningful because the searcher finds no answers or only negative answers. The second theme grows out of the first: Since tomorrow we die with nothing beyond, we should eat, drink, and be as merry as possible today.

The “ultimate pessimism” of The Rubaiyat is clear and explicit. Some lip-service is paid to the possibility of a rather capricious and irresponsible creator-God, but not even lip-service is given to the possibility of immortality. Death closes all, as the following lines attest:

Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend,

Before we too into the Dust descend;

Dust into Dust, and under Dust, to lie,

Sans Wine, sans Song, sans Singer, and—sans End! (Stanza 24)Then to the Lip of this poor earthen Urn

I leaned, the Secret of my Life to learn;

And Lip to Lip it murmured—“While you live,

Drink!—for, once dead, you never shall return.” (Stanza 35)Oh threats of Hell and Hopes of Paradise!

One thing at least is certain—This life flies;

One thing is certain and the rest is Lies —

The Flower that once has blown forever dies. (Stanza 63)

However much we may yearn for comforting answers to the perplexing questions of life, says The Rubaiyat, the yearning is in vain. We are trivial life-atoms in a mechanistic universe, and to ponder our origin or destiny or reason for existence is pointless.

And that inverted Bowl they call the Sky,

Whereunder crawling cooped we live and die,

Lift not your hands to It for help—for It

As impotently moves as you or I.With Earth’s first Clay They did the Last Man knead,

And there of the Last Harvest sowed the Seed;

And the first Morning of Creation wrote

What the Last Dawn of Reckoning shall read.Yesterday This Day’s Madness did prepare;

Tomorrow’s Silence, Triumph, or Despair.

Drink! for you know not whence you came, nor why;

Drink! for you know not why you go, nor where. (Stanzas 72, 73, and 74)

Nevertheless, though we are minute victims existing temporarily in a world without meaningful direction, we should not despair. Rather, we should live in the pleasures of the moment, seeking whatever satisfaction and significance they may provide. This carpe diem desire to snatch the utmost of pleasure from the irretrievable, fleeting moment is abundant throughout The Rubaiyat and makes the poem humanistic rather than existentialistic. Note the following typical lines:

Come, fill the Cup, and in the fire of Spring

Your Winter-garment of Repentance fling;

The Bird of Time has but a little way.

To flutter—and the Bird is on the Wing. (Stanza 7)A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness—

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!Some for the Glories of This World; and some

Sigh for the Prophet’s Paradise to come;

Ah, take the Cash, and let the Credit go,

Nor heed the rumble of a distant Drum! (Stanzas 12 and 13)Waste not your Hour, nor in the vain pursuit

Of This and That endeavor and dispute;

Better be jocund with the fruitful Grape

Than sadden after none, or bitter, Fruit. (Stanza 54)

Existentialism. Existentialism is “the conjunction of proximate pessimism with ultimate pessimism.” It is “the religion of meaninglessness and emptiness and despair; the religion that offers no hope here or hereafter, that finds man in his anxieties and leaves him there, that describes him as appetites that cannot be stilled, as impulsive striving that cannot be fulfilled, as passions that find no satisfaction, as irrational action guided by no integrated purpose.” Existentialism shares with fundamentalism a negative view with regard to the possibility of happiness or meaningful attainment in this life, and it shares with humanism a negative view with regard to the assurance of anything beyond this life. It leaves man with no function but to endure as best he can, to exist without purpose and without hope.17

Existentialism finds expression in quite a few writings of the later Victorian period. Both Hardy and Housman lean in this direction, fluctuating between the melancholy hedonism of The Rubaiyat and full negativism. In his Shropshire Lad and other poems Housman has a lilting surface manner almost as lyrically light and lovely as The Rubaiyat, but the underneath philosophy is even more grimly pessimistic. Hardy’s touch is not quite so light nor perhaps his philosophy quite so grim as Housman’s, but Hardy, with great compassion for those who suffer, also depicts people victimized by the double forces of a deterministic universe and an inhumane humanity. William Ernest Henley also is at times somewhat existentialistic, advocating defiant courage to endure the burden of life until its suffering is quelled by the black mystery of death (note “Invictus”). And Swinburne, that amazingly gifted young man with the elf-like body and leonine head who flaunted his paganism and exuberant love-and-hate passions before whatever startled audiences would listen, likewise at times seems totally pessimistic. For example, in the world-weary “Garden of Proserpine” Swinburne writes:

I am tired of tears and laughter,

And men that laugh and weep,

Of what may come hereafter

For men that sow to reap;

I am weary of days and hours,

Blown buds of barren flowers,

Desires and dreams and powers

And everything but sleep.

And the poem ends:

From too much love of living,

From hope and fear set free,

We thank with brief thanksgiving

Whatever gods may be

That no life lives forever;

That dead men rise up never;

That even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea.Then star nor sun shall waken,

Nor any change of light;

Nor sound of waters shaken,

Nor any sound or sight;

Nor wintry leaves nor vernal,

Nor days nor things diurnal;

Only the sleep eternal

In an eternal night.

But however pessimistic they are at times, Hardy, Housman, Henley, and Swinburne do not seem fully and consistently existentialistic. For such a point of view we need to turn to James Thomson (1834–1882),18 author of “The City of Dreadful Night.” In many of his little poems Thomson is grimly pessimistic. In “Two Sonnets,” for example, he explains that his songs are “all wild and bitter sad as funeral dirges” because “the bleeding heart cannot forever bleed / Inwardly solely; on the wan lips, too, / Dark blood will bubble ghastly, into view” and adds that his “grief finds harmonies in everything.” However, it is in “The City of Dreadful Night,” that nightmare shaped into a work of art,19 where Thomson most fully develops his bleakly negativistic philosophy and where we find the most total and consistent expression of existentialism.

Years filled with poverty, drunkenness, sickness, and death bludgeoned Thomson’s sensitive nature to a condition of total despair which culminated in the writing of his magnificently brutal masterpiece, which in its 1123 lines contains “the most formidable and uncompromising use of the speculations of the mechanistic materialists for the purposes of poetry.”20 Superficially the “city of dreadful night” is London with its midnight streets of poverty and crime and desolation, but symbolically21 the city is life and the agony of human existence. From the beginning to the end of the poem there is no cessation of the overwhelming gloom that smothers the reader through a relentless welter of grim phrases: “dead faith,” “mute despair,” “cold rage,” “false dreams,” “false hope,” “helpless impotence,” “termless hell,” “supreme indifference,” “unmitigated dearth,” “fatal gloom,” “unutterable sadness,” “incalculable madness,” “incurable despair.”

They leave all hope behind who enter there;

One certitude while sane they cannot leave,

One anodyne for torture and despair—

The certitude of Death. (lines 120–23)

Throughout the poem life is described as totally dismal and completely purposeless, with Death-in-Life as “the eternal king.” Confronted with such a dark view, one might well ask, as does a haunting figure in the poem,

“When Faith and Love and Hope are dead indeed,

Can Life still live? By what doth it proceed?” (lines 155–56)

And the narrator-poet answers with this bleak analogy:

“Take a watch, erase

The signs and figures of the circling hours,

Detach the hands, remove the dial-face;

The works proceed until run down although

Bereft of purpose, void of use, still go.” (lines 158–62)

In the powerful Section 4 of the poem Thomson recounts experiences in his life which compelled his total gloom. Two stanzas with their haunting desert-of-mortality refrain will suggest the mood and grim substance of this section:

“As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: Eyes of fire

Glared at me throbbing with a starved desire;

The hoarse and heavy and carnivorous breath

Was hot upon me from deep jaws of death;

Sharp claws, swift talons, fleshless fingers cold

Plucked at me from the bushes, tried to hold.

But I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“As I came through the desert thus it was,

As I came through the desert: On the left

The sun arose and crowned a broad crag-cleft;

There stopped and burned out black, except a rim,

A bleeding, eyeless socket, red and dim;

Whereon the moon fell suddenly southwest,

And stood above the right-hand cliffs at rest.

Still I strode on austere;

No hope could have no fear.” (lines 218–26 and 254–62)

Briefly his “soul grew mad with fear” when a sweetheart came into his life and kindled hope, but

A large black sign was on her breast that bowed,

A large black band ran down her snow-white shroud. (lines 284–85)

And with her death his unrelenting gloom returned that knew neither hope nor fear but only numbed existence with nothing to do but endure.

Beginning in Section 8 of the poem there is a debate between a demonist and a determinist—the demonist arguing that there is a creator God who out of malice and wild irresponsibility made earth and its suffering inhabitants, and the determinist arguing that no God, however capricious and irresponsible, could be blamed for the madness of the universe. The mechanistic-deterministic universe, says the determinist, is brutally hostile to man, but simply because it is that way—not because a God wills it that way.

“Man might know one thing were his sight less dim;

That it whirls not to suit his petty whim,

That it is quite indifferent to him.“Nay, does it treat him harshly as he saith?

It grinds him some slow years of bitter breath,

Then grinds him back into eternal death.” (lines 462–67)

Later in the poem a voice from the darkness reiterates even more explicitly that there is no God, no resurrection and immortality:

“I have searched the heights and depths, the scope

Of all our universe, with desperate hope

To find some solace for your wild unrest.“And now at last authentic word I bring,

Witnessed by every dead and living thing;

Good tidings of great joy for you, for all;

There is no God; no Fiend with names divine

Made us and tortures us; if we must pine,

It is to satiate no Being’s gall.“It was the dark delusion of a dream,

That living Person conscious and supreme,

Whom we must curse for cursing us with life;

Whom we must curse because the life He gave

Could not be buried in the quiet grave,

Could not be killed by poison or by knife.“This little life is all we must endure,

The grave’s most holy peace is ever sure,

We fall asleep and never wake again;

Nothing is of us but the moldering flesh,

Whose elements dissolve and merge afresh

In earth, air, water, plants, and other men.“We finish thus; and all our wretched race

Shall finish with its cycle, and give place

To other beings, with their own time-doom;

Infinite aeons ere our kind began;

Infinite aeons after the last man

Has joined the mammoth in earth’s tomb and womb.” (lines 719–45)

And still later the voice asserts:

“I find no hint throughout the Universe

Of good or ill, of blessing or of curse;

I find alone Necessity Supreme.” (lines 758–60)

Like Christina Rossetti, James Thomson looks forward to death. But whereas she anticipates a glorious outpouring after death for all that she was denied in life, he looks to death simply as the escape of oblivion ending the agony of life. Some people, he says, lament that “life is fleeting” and “time is deadly swift.” But his regret is that time drags, for

The hours are heavy on him and the days;

The burden of the months he scarce can bear;

And often in his secret soul he prays

To sleep through barren periods unaware. (lines 651–54)

The poisonously slow movement of time drives him almost mad:

Time which crawleth like a monstrous snake,

Wounded and slow and very venomous;

Which creeps blindwormlike round the earth and ocean,

Distilling poison at each painful motion,

And seems condemned to circle ever thus. (lines 660–64)

And he aches for the peace of annihilation:

O length of the intolerable hours,

O nights that are as aeons of slow pain,

O Time, too ample for our vital powers,

O Life, whose woeful vanities remain

Immutable for all of all our legions

Through all the centuries and in all the regions,

Not of your speed and variance we complain.We do not ask a longer term of strife,

Weakness and weariness and nameless woes;

We do not claim renewed and endless life

When this which is our torment here shall close,

An everlasting conscious inanition!

We yearn for speedy death in full fruition,

Dateless oblivion and divine repose. (lines 672–85)

The reader may wonder why, with such a philosophy, Thomson did not advocate suicide, or at least did not take his own life.22 But, anticipating full twentieth-century existentialism, he apparently found some compulsion, not purpose but compulsion, in the mere fact of existence. Even in this, as in his total philosophy, Thomson stands as Victorian England’s most powerful voice of existentialism.

Summary

Some literary periods are significant and interesting in the centrality of their philosophy. But, as previously stated, the Victorian Age was significant and interesting in its variety and conflict of philosophy. It was the fresh battleground upon which the war between faith and anti-faith was fought, the war that in our twentieth-century world is still being fought but now seems a little stale and muddled. In the age that ideologically stretched from Browning to James Thomson, the issues seemed clearer and the positions to be taken more sharply identifiable. That we can find in the first-quality literature of late nineteenth-century England vivid spokesmen for all four basic positions of liberalism, fundamentalism, humanism, and existentialism is evidence not only of the complexity of the age but also of its vigorous vitality—that age with its surface solidarity and equanimity and its underneath turmoil and ideological conflict.

About the author(s)

Dr. Clark is the chairman of the English Department at B.Y.U.

Notes

1. I am indebted to Dr. Sterling McMurrin for the definitions of these four terms as I have used them, with his permission, throughout this paper. In a 1954 lecture Dr. McMurrin (then Professor of Philosophy and later Academic Vice-President of the University of Utah, now just resigned after two years as U.S. Commissioner of Education) discussed liberalism, fundamentalism, humanism, and existentialism as the four basic compass points of religious attitude defined in terms of the concept of man. In employing these four terms I am aware, as Dr. McMurrin was also surely aware, that they are used in a somewhat limited sense with disregard for the entangled ramifications of meaning that have at times attached to their use. Especially is this true of humanism and existentialism, as evidenced in the latter, for example by the varied views of Søren Kierkegaard, Martin Heidegger, Jean Paul Sartre, Martin Buber, and Paul Tillrich. I have chosen to use the terms with exactly the same limitations of meaning that Dr. McMurrin employed for them. (See Dr. McMurrin’s The Patterns of Our Religious Faiths, Eighteenth Annual Fredrick William Reynolds Lecture, delivered at the University of Utah January 18, 1954, published by the University of Utah Extension Division as Bulletin no. 7, Volume 45.)

2. Ibid., pp. 12–16.

3. In Memoriam, Section 55.

4. “Crossing the Bar.”

5. See Sartor Resartus.

6. From the drama Pippa Passes.

7. McMurrin, op. cit., pp. 9–12.

8. She seems a better poet than her more famous brother Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and perhaps she is England’s greatest poetess, second as a poetess in our language only to America’s Emily Dickinson.

9. W. M. Rossetti, “Memoir” in The Poetical Works of Christina Georgina Rossetti (London: Macmillan and Company, 1904), p. liii.

10. Virginia Moore, Distinguished Women Writers (New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1934), p. 47.

11. And also with a point of view common in German romanticism. In fact, a study of this poem in relation to the whole movement of German romanticism would be rewarding.

12. McMurrin, op. cit., pp. 16–18.

13. Although in his essay Dr. McMurrin does not discuss hedonism as an aspect of humanism, it is a strong channel within humanism that should be recognized, at least in literature, and it becomes almost a “religion” for those who seriously advocate it.

14. See “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time.”

15. See “Sweetness and Light” in Culture and Anarchy.

16. Ibid.

17. McMurrin, op. cit., pp. 18–21.

18. Not to be confused with the eighteenth century nature poet having the same name who wrote “The Seasons.”

19. Samuel C. Chew, A Literary History of England, ed. Albert C. Baugh (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1948), p. 1418.

20. Ibid.

21. Much of the throbbing power of the poem comes through its image-symbols, with the “city” and the “desert” as the two controlling images unifying all the details into a terrifying whole, and with the eyes—burning, bleeding, glaring eyes—and the shroud as the two most vividly morbid secondary images, the latter with its charnel house, grave, and tomb references never letting the reader forget that the city is a city of death, not the death that ends all suffering but the infinitely more terrible death-in-life.

22. Actually he almost did. His death in 1882 was so fully a result of spiritual despair and physical dissipation that it was almost self-inflicted.

- The Spectrum of Faith in Victorian Literature

- The Pardoner as Huckster: A Dissent from Kittredge

- Background to the Theory of Arabic Origins

- “Snake”: A Moment of Consciousness

- The Reflections of Brigham Young on the Nature of Man and the State

- A New Emphasis for the American Dream

Articles

- Broken Ice

Creative Art

- New Address

- My victorious King receives his vestments from mocking

- O Cross, the old horror and fear of you are gone

- Great Sun, flame of Christ

- O Phoenix, cherished bird of Arabia

Poetry

- Index Volume IV: 1961–62

Indexes

Purchase this Issue

Share This Article With Someone

Share This Article With Someone