Knit Together

“That their hearts might be comforted, being knit together in love.”

—Colossians 2:2

The unusual thing about knit fabric is that it’s one continuous strand. Woven fabric consists of a warp and weft where individual strands arranged in a grid weave in and out, touching but ultimately separate. The knit fabric on everything from an ugly Christmas sweater to your favorite soft t-shirt looks like it’s made of hundreds of little “v” shapes, but it’s not. It loops in and through itself over and over and over, but it’s all connected. One long piece of yarn.

When Paul wrote to the Colossians that we should have our hearts knit together in love, did he understand this? Was he trying to tell us that we are not as separate as we appear? That we are all made of the same star-stuff, god-stuff, the fabric of the cosmos and of community? That you and I are not just you and I but one family of God?

•

I can’t really remember my first knitting project. I assume it was like most of the other first projects I’ve seen over the years: a cheap acrylic rectangle of variable width and thickness, nominally a scarf. In my imagination, it’s a shade of fuchsia and slightly fuzzy.

Did I learn to knit at a Young Women’s activity? It’s entirely possible. Certainly my mother didn’t teach me; her craft of choice was cross-stitch. All I remember clearly was that my first pair of needles were translucent blue plastic. My young teenage self worked hard to complete that lumpy swath of yarn, was proud that I had finished, and was perfectly content to be done with knitting after that one project.

I’m not sure if my sister picked up knitting from me or I from her. As sisters only fourteen months apart, our lives flowed together through many of the same tracks. We both wrote and read fan fiction. Each year, our parents bought us parallel but differently colored Christmas presents. When we stepped out of our junior-high art classes across the hall from each other, someone would inevitably say, “Oh my gosh, are you twins?”

But we couldn’t see it. I kept my side of our room neat, while her floor accumulated items like the gradual fall of snow—until suddenly it was six inches deep and our mother was demanding that a walkway be cleared. When my sister was interested in cooking, I couldn’t be. When I chose academics over hanging out with friends, she had to do the opposite just to feel like herself. We differentiated ourselves by fleeing to the ends of the spectrum.

Knitting felt like one of those things. Possibly because I had neglected it, my sister picked up knitting and ran with it. A collection of needles of various sizes and colors appeared and scattered across her room. She discovered online knitting magazines full of stylish projects—lots of boho wrist warmers and tams. Often on Saturday afternoons, she would sit on the worn plaid couch in the basement, watching the extended editions of The Lord of the Rings while she worked through the long stretches of a scarf. This happened so many times that she memorized even the commentary tracks. Knitting became part of who she was, a part that separated us, like the many other things that we began to fight over as we grew our separate ways toward adulthood.

•

The language of knitting patterns takes some time to get used to. It’s full of arcane lowercase acronyms that appear like an alien language: slwyib (slip the stitch with yarn in back), kfbf (knit through the front, back, and front again), m3 (make three new stitches). The amazing thing is that a two-dimensional text will eventually sculpt your straight rows into the three-dimensional reality of a hat or a sweater. Two stitches will start far apart and then through a series of gradual decreases be brought together. You don’t need to understand why. You can’t go wrong if you just follow the pattern. And if you’re lucky, at some point in your work, you’ll have a flash of insight where you can suddenly see how all these steps are adding up.

When Paul talked about hearts knit together in love, did he understand this? Was he trying to explain that human relationships aren’t always understandable? That where we were is not always where we will be? That sometimes the directions of our lives and relationships make sense only in retrospect?

•

I picked up knitting again in college as a way to keep myself focused in class. I found note-taking tedious, but having a craft in my hands kept my mind on the lecture. My freshman year, as the professor lectured about ancient Greek philosophy, a bumpy purple-and-red-variegated yarn looped over my new wooden needles, gradually forming a pair of wrist warmers.

Just like the ones my sister used to make.

As the older sister, I was embarrassed to be jealous of my younger sister’s coolness. At the end of our teen years, we had been so different that she’d shut me out of her life, rarely talking even though our bedroom doors were six feet apart. But I needed help with my next project, so I called her up.

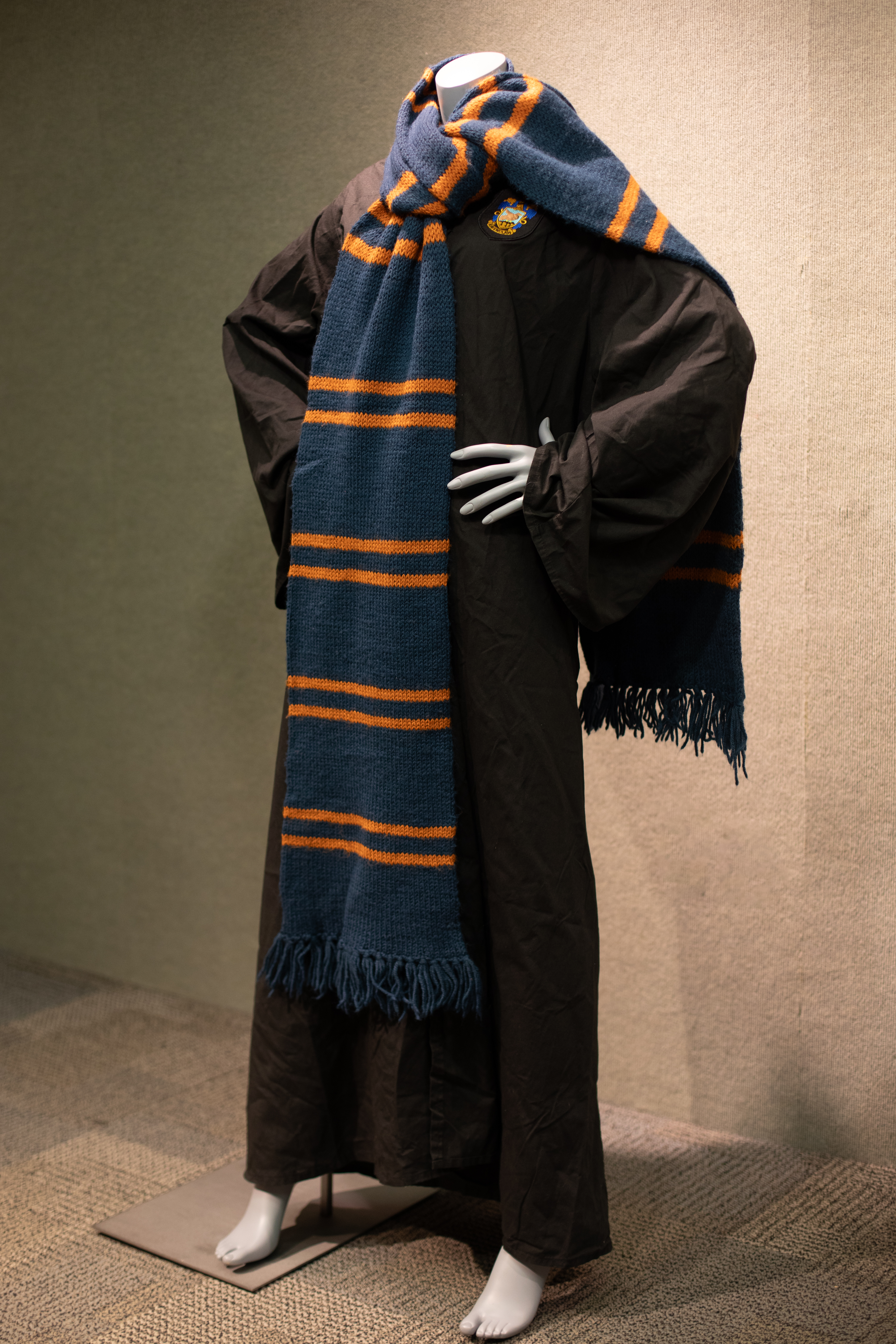

It turned out she was excited to teach me about something she loved. One phone call became more. We began to talk frequently on the phone and at the holidays about the latest patterns on Knitty, about the intricacies of intarsia (in which you knit two layers of yarn at the same time to make a two-colored pattern), about whether to use double-pointed needles or the magic loop method for knitting socks. With my sister’s sage advice, I made a Harry Potter scarf knit in the round rather than worked flat, which would have saved time but looked terribly amateur.

Courtesy Liz Busby. Photograph by Cooper Douglass.

Courtesy Liz Busby. Photograph by Cooper Douglass.As we talked, I found my sister again as she began to ask me for advice in return: what classes she should take, how to write that analysis of a Shakespearean sonnet, and how to deal with her roommates who would never do the dishes. I didn’t always understand why some things that seemed obvious to me came with such difficulty to her, but I tried to give her the benefit of the doubt. Though our campuses were hours apart, we were suddenly, strangely closer than we’d ever been under the same roof.

•

What makes knitting different from crochet is that all of the stitches are live all of the time. With crochet, you only have to deal with one open loop at a time, while the rest of the piece is safe from unraveling. With knitting, the entire length of your piece is a liminal edge, little loops of possibility. Should you drop one and not notice, every stitch below it will come undone. You’ll have to pause and go down the column, picking up all the stitches that depended on the one you lost.

When Paul talked about hearts knit together in love, did he understand this? Was he trying to tell us that we have not one relationship but many? That when we establish new relationships, we still need to keep an eye on the others? That the greatest lie in the world is that we could practice self-care apart from the web of relationships that comprise us?

•

The biggest knitting project I’ve ever taken on was making Christmas stockings. The pattern was called “New Ancestral Christmas Stockings,” and it was just as pretentious as it sounds. It was full of complex patterns involving techniques like intarsia and duplicate stitching, all meant to create a stocking composed of three blocks: a plaid, a stripe, and a gorgeous snowflake. As a young mother looking to establish our family’s Christmas culture, I fell in love with it—not considering that I’d be making three of these, one each for me, my husband, and our one-year-old son. Each one took a lot of work; by the time I’d finished the ones for the adults, I’d decided to simplify the baby’s by taking out the snowflake block.

Courtesy Liz Busby. Photograph by Cooper Douglass.

Courtesy Liz Busby. Photograph by Cooper Douglass.Then Christmas chocolate somehow melted all over my son’s stocking during the festivities. In my rush, I forgot the cardinal rule of wool and threw it in the wash, wherein it quickly shrunk and matted into felt. I cried when I thought of all that wasted work. Next year, I’d have to knit him another one along with one for the new baby.

I complained about it on the phone to my sister, now three states away. We were still talking regularly, sometimes about knitting, sometimes to brainstorm an ending for her latest novel, sometimes to discuss her struggles with her latest singles ward.

I don’t remember when our conversations changed. Three stockings became five. I was constantly tired, chasing three boys around the house and across the playground and into the bathtub. I was too exhausted to write, much less be thoughtful of others. But this is all an excuse. Looking back, I can see that the signs were there in our phone conversations, but I missed them.

“How come I always have to call you?”

In truth, I never called anyone because I was always just trying to keep my head above water or steal a few moments of silence for my introverted brain to recover from the constant noise. I was too exhausted even to write a few sentences.

“Don’t you have any problems?”

Mostly, my problems were things she couldn’t relate to, like childcare questions I outsourced to my playgroup. Other issues I kept between me and my husband. Did she think that because I didn’t complain to her that my life was perfect? Or that I didn’t care about her problems just because I kept mine to myself?

Looking back, I understand now that it could have been exactly that. Or perhaps it was too painful for her to keep talking to me when my life continued to move along the expected track while she felt hers was going off the rails. I didn’t notice. Our conversations went from weekly to monthly, then disappeared entirely.

•

Nothing induces dread in a knitter as much as finding an unexplained hole in a hand-knitted sweater or sock. Sometimes a piece gets snagged on something and rips; other times, the yarn just tires after years of tension and pulls apart. After all, it’s just fibers spun together. There’s no glue, just the gentle twist of the plies and interlocking stitches. But there’s a sense in which the panic provoked by a hole is absolutely justified. All of your hard work can evaporate as the stresses of normal wear will cause the hole to expand in all directions until it becomes irreparable. The worst thing you can do in this situation is to pull on or cut the ends that are sticking out. The yarn must be carefully rethreaded through the pattern of the lost stitches, rejoined, and knotted back together, or it will continue to unravel.

When Paul talked about hearts knit together in love, did he understand this? Was he trying to tell us to notice problems when they are small and repair them quickly? That the hurt will only grow, not diminish, if we try to pull those lost threads? That the human heart is a matter of delicacy and urgency?

•

When we decided to move back to Utah halfway through the COVID-19 pandemic, I was forced to confront the mass of knitting supplies I had acquired over the years: leftover yarn from the baby blankets I’d made for each of my kids, incomplete sets of double-pointed needles I’d lost in various couches, the jars of plastic eyes from when I’d gone through a phase of knitting stuffed animals. All remnants of a time when I’d poured my creativity into something I could do on autopilot while watching kids race cars down a track over and over again. But I hadn’t opened some of these boxes in years. As my kids were growing older and more self-sufficient, my mind returned to writing, and perhaps I didn’t need knitting as much anymore. But I had such good memories with it that I couldn’t let it go entirely. I winnowed my yarn and supplies down into one set of plastic drawers, wrapped clear packing tape around it, and loaded it into the moving van.

We could have moved anywhere, but I longed for my kids to have a relationship with their grandparents beyond what our biannual visits could bestow. It would be good for them to have aunts and uncles in their life to set examples for them, form more connections with them, tell them how things are when their parents can’t get through.

But partly it was for me. I wanted to have closer relationships with my siblings. Sometimes my inability to maintain long-distance relationships felt like a moral failing. Then again, perhaps there’s a reason that the Church is organized around geographic wards. Contact breeds closeness.

Or at least I hoped so. I depended on this principle to bring my sister back to me.

We started seeing each other at least a couple times a month, but sometimes it still felt like we were states away. After Sunday dinner, I’d sit at the table playing a board game, talking with my other siblings, while she would sit on the couch with her knitting, refusing to be drawn into the game. Was she genuinely interested in what my dad was watching on the TV, or was she actually stewing over something I had said? I could never tell. I was afraid to ask her if she was still writing, if she was dating again, how she was doing beyond the most basic of small talk, because I didn’t want to seem pushy.

Perhaps I should have asked.

I can’t even recall now the words that I said. All I know is that on Christmas Day she stormed out. After an exchange of angry emails and texts, she let me know that she’d no longer be attending any family event I was present at.

•

The scariest knitting technique, in my opinion, is Norwegian sweater steeking. You knit a solid tube of fabric, usually with an intricate fair-isle pattern. To add the sleeves and introduce shaping, you have to do the one thing you should never do: take scissors and cut through each of your stitches straight up the middle. Sure, you add some machine sewing to reinforce the edges beforehand, and theoretically the sticky quality of the wool should keep the pattern from unraveling. Still, it’s so stressful that some knitters joke that a bottle of beer is a required part of the process, to steel the nerves before the first slice.

When Paul talked about hearts knit together in love, did he understand this? Was he trying to tell us that against all instinct, sometimes our relationships must be broken in order to be reshaped? That our final form may not be the one we started in? That we must trust the process even when it seems to be destroying everything we worked so hard for?

•

Lately I find myself writing more than knitting. Still, writing can be stressful, especially when you’re trying to build a career. To give myself a break from deadlines and expectations, I started a knitting project—a shawl with stripes of blue, beige, white, and orange yarn that came in a color pack called London Fog. Somehow, two years later, it’s still incomplete, languishing in my drawer, brought out every few months as I tell myself with fervor that this time I will finish it.

Over and over, I find myself writing about broken relationships being mended. I try to write the characters in a balanced way on both sides, really allowing the reader to gain sympathy for both parties. To give the sense that we are all real people, that our problems can be solved, but that the solution is not “if only they would change.” The reconciliation should not require one to admit the other was right, and yet it should feel real, like both sides are compromising to come together again into something new. I fiddle with the words, trying to create what I can’t find.

Courtesy Liz Busby. Photograph by Cooper Douglass.

Courtesy Liz Busby. Photograph by Cooper Douglass.Yet in real life, it’s never that easy. I often can’t see the beam in my own eye in my rush to clear the mote from my sister’s eye. I pray over and over for my heart to see more clearly.

Perhaps, like my latest shawl project, it will just take time, faith, and hope. Time for the ripped seams to be stitched back together. Faith that the man who understood carpentry and fishing and shepherding also understands this process of knitting. Hope that my relationship with my sister is not ultimately a dropped stitch, a hole, or a ripped seam, but part of a larger pattern.