Notes

1. Nihm is also variously spelled Nahm, Naham, Nehhm, Nehem, and so on.

2. The first person to propose this connection was Ross T. Christensen in his October 8, 1977, presentation at the twenty-sixth annual symposium of the Society for Early Historic Archaeology (SEHA) at BYU. See Ruth R. Christensen, “Twenty-Sixth Annual Symposium Held,” Newsletter and Proceedings of the SEHA 141 (December 1977): 9; Ross T. Christensen, “The Place Called Nahom,” Ensign 8, no. 8 (August 1978): 73. See also “Some Possible Identifications of Book of Mormon Sites,” Newsletter and Proceedings of the SEHA 149 (June 1982): 11.

3. For a summary of the Latter-day Saint literature about these inscriptions, see Warren P. Aston, “A History of NaHoM,” BYU Studies Quarterly 51, no. 2 (2012): 78–98. Key publications include S. Kent Brown, “‘The Place That Was Called Nahom’: New Light from Ancient Yemen,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 8, no. 1 (1999): 66–68; Warren P. Aston, “Newly Found Altars from Nahom,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 2 (2001): 56–61, 71; “Book of Mormon Linked to Site in Yemen,” Ensign 31, no. 2 (February 2001): 79; S. Kent Brown, “New Light from Arabia on Lehi’s Trail,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002), 81–83; Stephen D. Ricks, “On Lehi’s Trial: Nahom, Ishmael’s Burial Place,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20, no. 1 (2011): 66–68; Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 105–108; Warren P. Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia: The Old World Setting of the Book of Mormon (Bloomington, Ind.: Xlibris, 2015), 79–85.

4. See John M. Lundquist, “Biblical Seafaring and the Book of Mormon,” in Raphael Patai, The Children of Noah: Jewish Seafaring in Ancient Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998), 173; Terryl L. Givens, By the Hand of Mormon: The American Scripture that Launched a New World Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 120–21, 147; Terryl L. Givens, The Book of Mormon: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 117–18; John A. Tvedtnes, “Names of People: Book of Mormon,” in Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, 4 vols., ed. Geoffrey Khan (Boston: E. J. Brill, 2013), 2:787; Grant Hardy, “The Book of Mormon,” in The Oxford Handbook of Mormonism, ed. Terryl L. Givens and Philip L. Barlow (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 143.

5. Givens, By the Hand of Mormon, 120.

6. For a response to previous criticisms, see Neal Rappleye and Stephen O. Smoot, “Book of Mormon Minimalists and the NHM Inscriptions: A Response to Dan Vogel,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 8 (2014): 157–85.

7. RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia: A Historical Perspective, Part 2,” Faith-Promoting Rumor (blog), October 6, 2015, accessed May 25, 2023, https://faithpromotingrumor.com/2015/10/06/nahom-and-lehis-journey-through-arabia-a-historical-perspective-part-2/.

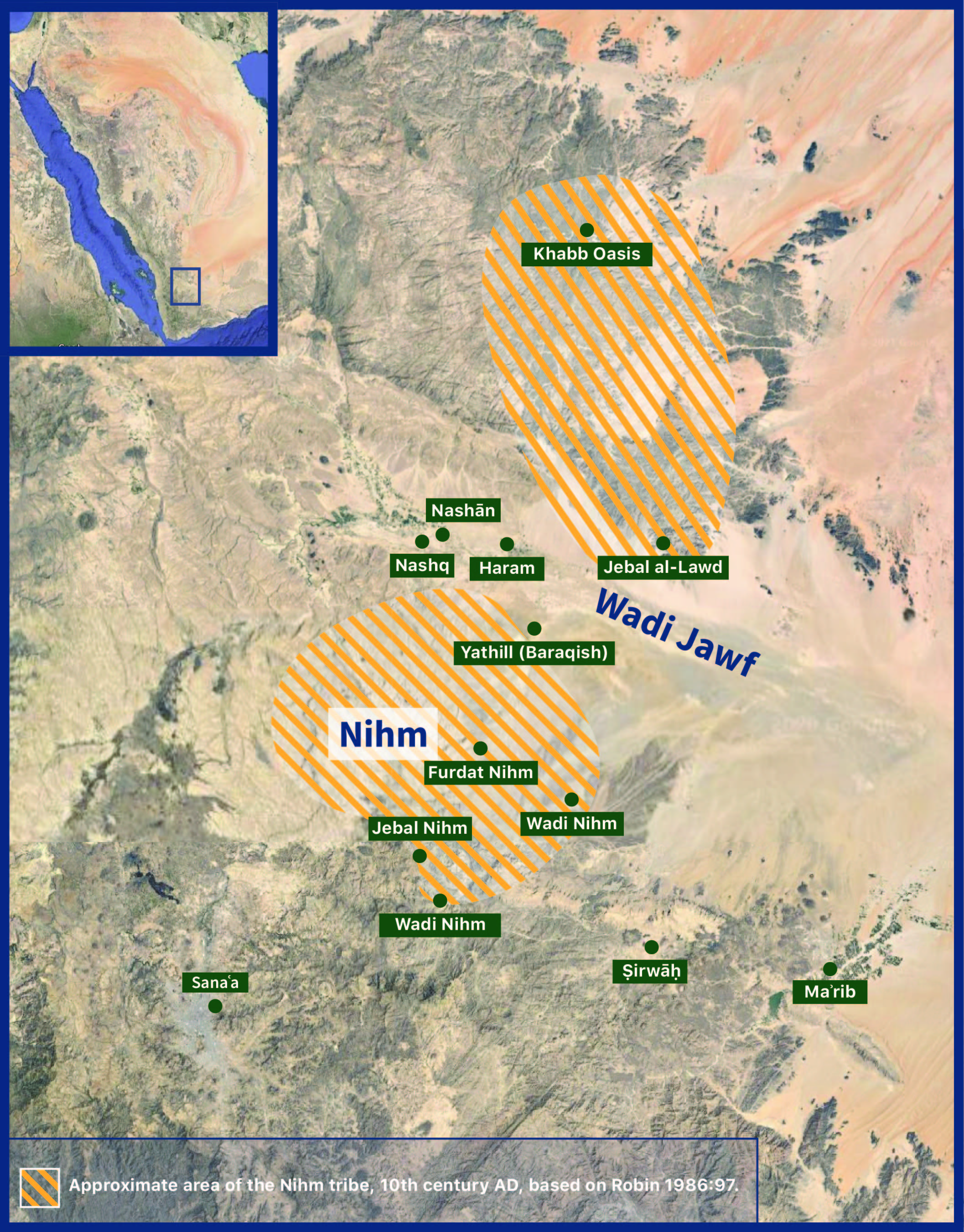

8. Unfortunately, as part of Yemen’s ongoing civil war, the Nihm region has been ground zero for several conflicts within recent years. See “Nihm Offensive,” Wikipedia, accessed May 25, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nihm_Offensive. Although the last reported conflict involving the Nihm was in January 2020, as of this writing the larger conflict remains unresolved, so it is hard to say if there will be any long-term impacts on political and tribal boundaries.

9. RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia.”

10. RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia.” For a previous response to this argument, see Jeff Lindsay, “Nahom/NHM: Only a Tribe, Not a Place?,” Arise from the Dust (blog), August 5, 2022, accessed May 25, 2023, https://www.arisefromthedust.com/nahom-nhm-only-a-tribe-not-a-place/.

11. This is unsurprising, since many of the administrative districts in northern Yemen are named after established tribes whose names have long been associated with the regions they occupy. For several examples, see the discussion of various tribes in Marieke Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen: A History of the Houthi Conflict (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 24–34, many of which have an eponymous district whose borders are roughly equivalent to the tribal territory. In a few instances, however, Brandt notes cases where a tribe’s territory is more expansive than the administrative district by the same name (for example, the Rāziḥ tribal territory expands beyond the Rāziḥ district into the neighboring Shidā’ district, pp. 27–28). Compare Marieke Brandt, “The Concept of Tribe in the Anthropology of Yemen,” in Tribes in Modern Yemen: An Anthology, ed. Marieke Brandt (Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 2021), 12: “In the 20th century, these tribal territories became the basis of the administrative divisions of northern Yemen; the borders of most of today’s districts (sg. mudīriyyah) and municipalities (sg. ʿuzlah) are congruent with the boundaries of the tribes and tribal sections that inhabit them.”

12. Warren P. Aston and Michaela J. Aston, “The Search for Nahom and the End of Lehi’s Trail in Southern Arabia,” FARMS Paper (1989), 6.

13. Matsumoto specifically notes that the Nihm nāḥiyah “consist[ed] of only one tribe” and “the territorial names of the regional division . . . [within the Nihm nāḥiyah] correspond to the names of tribal sections completely.” Hiroshi Matsumoto, “The History of ʿUzlah and Mikhlāf in North Yemen,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 24 (1994): 176.

14. Christian Robin, “Nihm: Nubdha fī ʾl-jughrāfiyya al-taʾrīkhiyya wafqan li-muʿṭiyāt al-Hamdānī,” in Al-Hamdani: A Great Yemeni Scholar, Studies on the Occasion of His Millennial Anniversary, ed. Yusuf Mohammad Abdallah (Sanaʿa, Yemen: Sanaʿa University, 1986), 84–87, 98 (map).

15. Ahmed Fakhry, An Archaeological Journey to Yemen (March–May 1947), 3 vols. (Cairo: Government Press, 1952), 1:13. This is while he is traveling in Wadi Hirran, south of the Jawf (El Gōf; see figure 1 on 1:3). See also 1:22, where he talks about Joseph Halévy’s travels in “the land of the tribe of Nihm.”

16. Harry St. John Philby, Sheba’s Daughters: Being a Record of Travel in Southern Arabia (London: Methuen and Co., 1939), 381. Later he refers to the region as “the country of the Nahm tribe” (398).

17. Warren P. Aston, “The Origins of the Nihm Tribe of Yemen: A Window into Arabia’s Past,” Journal of Arabian Studies 4, no. 1 (2014): 141, documents Nihm on official government maps from 1961, 1962, 1968, 1976, 1978, and 1985. Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia, 75–76, supplements those references with additional maps from 1939, 1945, and 1974.

18. See Alan Verskin, trans., A Vision of Yemen: The Travels of a European Orientalist and His Native Guide, a Translation of Hayyim Habshush’s Travelogue (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2018), 87–88, 96–105, 114–121, 238 n. 39. In the Hebrew version of Ḥabshūsh’s account, “land of Nihm” appears as ארץ נהם (eretz NHM). See, for example, Ḥayyim Ḥabshūsh, Ruʾyal al-Yaman (Masʿot Ḥabshūsh), ed. S. D. Goitein (Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 1983), 33.

19. See “Map of locations mentioned in Ḥayyim Ḥabshūsh’s Vision of Yemen,” in Verskin, Vision of Yemen, [xvii].

20. See Bulletin de la Société de Géographie 6, no. 6 (1873): 16, 36, 112–13 (map), 260–61, 270. Halévy’s map is conveniently reprinted in Verskin, Vision of Yemen, [xvi].

21. See Aston, “Origins of the Nihm Tribe,” 139–41; Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia, 75. See also James Gee, “The Nahom Maps,” Journal of Book of Mormon and Restoration Scripture 17, no. 1 (2008): 40–57.

22. See Gee, “Nahom Maps,” 42.

23. See Thorkild Hansen, Arabia Felix: The Danish Expedition of 1761–1767, trans. James McFarlane and Kathleen McFarlane (New York: New York Review Books, 1964). For Niebuhr’s own account of his travels, see Carsten Niebuhr, Travels through Arabia, and Other Countries in the East, 2 vols., trans. Robert Heron (Edinburgh: R. Morrison and Son, 1792–99).

24. See Gee, “Nahom Maps,” 42–43.

25. As mentioned above, Robin estimated that the Nihm tribal lands covered 5,000 square kilometers, which converts to about 1,931 square miles. Robin, “Nihm.”

26. Niebuhr, Travels through Arabia, 2:37, 50.

27. See Gee, “Nahom Maps,” 40–42.

28. See Aston, “Origins of the Nihm Tribe,” 139.

29. See Aston, “Origins of the Nihm Tribe,” 139; Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia, 76–77.

30. See Paul Dresch, Tribes, Government, and History in Yemen (New York: Clarendon Press, 1989), 320–29; Robert Wilson, “Al-Hamdānī’s Description of Ḥāshid and Bakīl,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 11 (1981): 95–104.

31. See Robin, “Nihm,” 87–93, 97 (map). See also Christian Robin, “Le Pénétration des Arabes Nomades au Yémen,” Revue du Monde Musulman et de la Méditerranée 61, no. 1 (1991): 85. However, this may imply more movement/change of the tribal geography than really exists, since according to Serguei Frantsouzoff, the Nihm tribe was still divided into to two factions as recently as the 1970s, one living in the present-day Nihm region and the other living in the Amir region to the northwest of the Wadi Jawf. Sergui Frantsouzoff, Nihm, 2 vols. (Paris: Diffusion De Boccard, 2016), 1:9. Nonetheless, the Nihm name is no longer topographically applied to the region north of the Jawf, and the Nihm do not control any territory to the north, even if pockets of the tribe remain there.

32. See David Heinrich Müller, ed., Al-Hamdânî’s Geographie der arabischen Halbinsel: Nach den Handschriften von Berlin, Constantinopel, London, Paris und Strassburg, 2 vols. (Leiden, Neth.: E. J. Brill, 1884–1891), 1:49.9; 81.4, 8, 11; 83.8–9; 109.26; 110.2, 4; 126.10; 135.19, 22; 167.15, 19–20; 168.10, 11. See also D. M. Dunlop, “Sources of Gold and Silver in Islam According to al-Hamdānī (10th Century AD),” Studia Islamica 8 (1957): 41, 43.

33. See Werner Caskel, Ǧamharat an-nasab: das genealogische Werk des Hišām Ibn Muhammad al-Kalbī, 2 vols. (Leiden, Neth.: E. J. Brill, 1966), 2:46–47; Jawad ʿAli, Al-Mufassal fi Taʾrikh al-ʿArab qabla al-Islam, 10 vols. (Beirut: Dar al-ʿIlm lil-Malayin, 1969–1973), 4:187; 7:414.

34. See Aston, “The Origins of the Nihm Tribe,” 139. An Arabic transcription and partial English translation of the letter can be read in Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia, 77.

35. On the borders of the Hamdan in early Islamic sources, see Christian Robin, Les Hautes-terres du Nord-Yemen avant L’Islam, Part 1: Recherches sur la géographie tribale et religieuse de H̲awlān Quḍāʿa et du Pays de Hamdān (Istanbul: Publications de l’Institut historique-archéologique néerlandais de Stamboul, 1982), 41; Christian Julien Robin, “Matériaux pour une prosopographie de l’Arabie antique: les noblesses sabéenne et ḥimyarite avant et après l’Islam,” in Les préludes de l’Islam: Ruptures et continuités dans les civilisations du Proche-Orient, de l’Afrique orientale, de l’Arabie et de l’Inde à la veille de l’Islam, ed. Christian Julien Robin and Jeremie Schiettecatte (Paris: De Boccard, 2013), 268, map 4. Since the Nihm were already established in that region when the Hamdan confederation converted to Islam, their origins in the region must go back earlier still.

36. Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, 18.

37. Barak A. Salmoni, Bryce Loidolt, and Madeleine Wells, Regime and Periphery in Northern Yemen: The Huthi Phenomenon (Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND, 2010), 47.

38. Dresch, Tribes, Government, and History in Yemen, 75.

39. Dresch, Tribes, Government, and History in Yemen, 77–78.

40. Dresch, Tribes, Government, and History in Yemen, 78. Compare Salmoni and others, Regime and Periphery, 47, who quote a Yemeni proverb, ‘izz al-qabili biladah, meaning “the pride/prestige of a tribe is his land” (translation adapted from Salmoni and others).

41. Dresch, Tribes, Government, and History in Yemen, 80. Compare Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, 19: “The protected space on which tribal honour depends is often identified with physical space: that is, with territory.”

42. Najwa Adra, “Qabyalah or What Does it Mean to be Tribal in Yemen?,” in Tribes in Modern Yemen, 21–38, not only defines qabīlah (the Yemeni term for tribe) as “indigenous territorial groups” (p. 22) but also as “a bounded territorial unit.”

43. See Brandt, “The Concept of Tribe,” 12 n. 8, wherein she notes, “In some cases, the continuity of tribal names and their related territories spans almost three millennia.” Significantly, she cites work on the history of Nihm in support of this claim.

44. For background on these genealogies, see Christian Julian Robin, “Tribus et territoires d’Arabie, d’après les inscriptions antiques et les généalogies d’époque islamique,” Semitica et Classica 13 (2020): 225–36.

45. See Aston, “Origins of the Nihm Tribe,” 136. The Nihm are still part of Bakīl today (see Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen, 30; Dresch, Tribes, Government, and History in Yemen, 24, table 1.2; Salmoni and others, Regime and Periphery, 50, fig. 2.2; Robert D. Burrowes, Historical Dictionary of Yemen, 2nd ed. [Lanham, Md.: The Scarecrow Press, 2010], 6–7, 157–58).

46. Marieke Brandt, “Heroic History, Disruptive Genealogy: Al-Ḥasan al-Hamdānī and the Historical Formation of the Shākir Tribe (Wāʾilah and Dahm) in al-Jawf, Yemen,” Medieval Worlds: Comparative and Interdisciplinary Studies 3 (2016): 116–45; Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 225–36.

47. Brandt, “Heroic History,” 118: “Studies on tribal genealogy show that descent lines are in most cases the results of manifold processes of tribal fusion and fission and sometimes even pure constructs. . . . Tribal structures and genealogies are seldom stable, but rather dynamic and deformable so that new political constellations, alliances and territorial changes can be facilitated by genealogical alignments. In many cases genealogy follows a politics of ‘must have been’ rather than biological facts.” Brandt adds that “descent and genealogy are . . . the vocabulary through which [political and territorial] relations [of the tribes and tribal segments] are expressed, regardless of, and often in contradiction to, known biological facts” (p. 136). Compare Adra, “Qabyalah,” 22: “Some tribal units self-define in genealogical terms but, as is the case elsewhere, genealogies are used flexibly and manipulated to justify new relationships or break off old ones.”

48. See Brandt, “Heroic History,” 137. Compare Adra, “Qabyalah,” 23: “Because of the widespread use of genealogical idioms, tribes are often described as kin groups. Yet in Yemen and elsewhere, most tribal units are territorial, with kinship terminology providing a metaphor to indicate closeness or distance.”

49. Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 236.

50. Brandt, “Heroic History,” 137.

51. Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 232, 235–36.

52. Brandt, “Heroic History,” 136.

53. See Alessandra Avanzini, By Land and By Sea: A History of South Arabia before Islam Recounted from Inscriptions (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2016), 57; Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 206–7.

54. See Robin, Les Hautes-terres du Nord-Yemen, 71–72; Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 217–18; Christian Robin, “Le problème de Hamdān: Des qayls aux trois tribus,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 8 (1978): 46–52; Andrey Korotayev, “Sabaean Cultural Area in the 1st–4th Centuries AD: Political Organization and Social Stratification of the Shaʿb of the Third Order,” Studi Epigrafici e Linguistici 11 (1994): 129–34; Andrey Korotayev, Ancient Yemen: Some General Trends of Evolution of the Sabaic Language and Sabaean Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press; Manchester: University of Manchester, 1995), 2–3.

55. Jean-François Breton, Arabia Felix from the Time of the Queen of Sheba: Eighth Century BC to First Century AD, trans. Albert LaFarge (Norte Dame, Ind.: University of Norte Dame, 1999), 96. In contrast to Breton’s view that the “tribe took its name from the territory,” Robin, Les Hautes-terres du Nord-Yemen, 27, reasons that regional names in the highlands, such as Arḥab, Nihm, Ḥaraz, or Ǧahrān, were tribal names first and then by extension the names of the tribal territory. In any case, the firm connection between tribe and territory is indisputably evident.

56. Breton, Arabia Felix, 95–96. See also Robin, Les Hautes-terres du Nord-Yemen, 72–73; A. F. L. Beeston, “Kingship in Ancient South Arabia,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 15, no. 3 (1972): 258.

57. Joan Copeland Biella, Dictionary of Old South Arabic: Sabaean Dialect (Cambridge: Harvard Semitic Studies, 1982), 520, emphasis added. Compare A. F. L. Beeston, M. A. Ghul, W. W. Müller, J. Ryckmans, Sabaic Dictionary (English-French-Arabic) (Sanaʿa: University of Sanaʿa, 1982), 130, “sedentary tribe, commune, group of village communities” (emphasis in original). This strong territorial association is the reason some prefer the translation of “community” or “commune” over “tribe” for this term. Robin, “Matériaux pour une prosopographie de l’Arabie antique,” 134. To this day, shaʿb, defined as “people, tribe, nation,” is commonly used in Arabian toponymy. Nigel Groom, A Dictionary of Arabic Topography and Placenames: A Transliterated Arabic-English Dictionary (Beirut: Librairie du Liban; London: Longman, 1983), 264.

58. Avanzini, By Land and By Sea, 58. Compare Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 218–19.

59. Avanzini, By Land and By Sea, 59, emphasis added. Alternatively, Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 214–15, says that nisba forms only specified an individual’s tribal affiliation and did not (or only rarely) link their identity to city or territory. However, since Robin agrees that tribes were territorially based, and also goes on to say (as quoted in the body of the text) that territories are primarily named after tribal groups, it seems he is splitting hairs here.

60. Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 215, translation mine. The original French reads: “Pour nommer les régions et les territoires, les Sudarabiques se réfèrent normalement à l’organisation politico-tribale, c’est-à-dire aux royaumes et aux groupes tribaux.” Robin goes on to add, “Although geographical appellations are sometimes used to identify territories, they are much less frequent than references to political and tribal divisions” (“Si, pour identifier les territoires, les appellations géographiques sont parfois utilisées, elles sont beaucoup moins fréquentes que la référence aux divisions politiques et tribales,” translation mine).

61. Robert G. Hoyland, Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam (New York: Routledge, 2001), 116.

62. See Robin, Les Hautes-terres du Nord-Yemen, 73: “pour designer un territoire, on se sert habituellement de noms de šʿb precedes ou non du mot ʾrḍ (‘terre, pays’),” translation mine. Compare Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 215: “The most common expression is to say ‘the Land of’ (arḍ, ʾrḍ) followed by a kingdom or tribal group name, e.g. ‘the Land of Ḥimyarum’ or ‘the Land of Madhḥigum’” (“La tournure la plus commune consiste à dire ‘le Pays de’ (arḍ, ʾrḍ) suivi par un nom de royaume ou de groupe tribal, par exemple ‘le Pays de Ḥimyarum’ ou ‘le Pays de Madhḥigum,’” translation mine). It is hard to square all these statements from Robin with his claim that tribal names “are not toponyms” and “in general, there is no confusion. The inscriptions distinguish always between Ḥimyar [a south Arabian tribe] and ‘the Land of Ḥimyar’” (personal communication to RT, July 27, 2015, quoted in RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia”). Robin actually makes a very similar statement in Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 214: “In the mountains of Yemen, the categories ‘social groups’ and ‘toponyms’ are always distinguished” (“Dans la montagne du Yémen, les catégories ‘groupes sociaux’ et ‘toponymes’ sont toujours distinguées,” translation mine). It seems to me, in context, that Robin is perhaps meaning to say that tribes do not generally derive their names from toponyms or geographical terms (compare n. 55 herein), not that tribal names were not used as toponyms. There are scholars who appear to differ with Robin on this point (see nn. 55, 59, 88 herein), and Robin himself notes that this actually varies by region (pp. 214–15). In any case, in light of these additional statements from Robin (not to mention other scholars cited here), and even the epigraphic evidence discussed in this paper, it seems misguided to use this statement from Robin to claim that “it does not make sense to speak of Nihm as though it were a regular place name.” RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia.”

63. See Robin, Les Hautes-terres du Nord-Yemen, 73; Hoyland, Arabia and the Arabs, 116, for examples beyond those given here.

64. For “the land of Ḥaḍramawt” (ʾrḍ ḤḌRMWT), see epigraphs CIAS 39.11/o 3 no 4, Ir 13, MB 2002 I-28, and B-L Nashq, Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions (hereafter CSAI), accessed May 31, 2023, http://dasi.cnr.it/index.php?id=26&prjId=1&corId=0&colId=0&navId=0.

65. See, for example, “he came back towards THMT and Ḥa[ḍramawt]” in CIH 597, and “[to]wns and fortresses of Ḥaḍramaw[t]” in CIH 948, CSAI.

66. For “the land of Ḥimyar” (ʾrḍ ḤMYRM), see Antonini 1998, BR-M Bayḥān 4, CIAS 39.11/o 1 no 1, CIAS 39.11/o 2 no 3, CIH 155, CIH 343, CIH 350, CIH 621, Ja 576+577, Ja 578, Ja 579, Ja 580, Ja 586, Ja 740, CIAS 39.11/o 3 no 5, Gr 185, Ir 9, MAFRAY-al-Miʿsāl 5, Ry 548, YM 18307, CSAI. See also the example of “the land of the Ḥabashites” (ʾrḍ ḤBS2T) in CIH 621, CSAI.

67. See RES 2687, CSAI.

68. Maʿīn 1, Maʿīn 87, Maʿīn 88, YM 26106, CSAI.

69. M 247, CSAI. See also Rémy Audouin, Jean-François Breton, and Christian Robin, “Towns and Temples: The Emergence of South Arabian Civilization,” in Yemen: 3000 Years of Art and Civilization in Arabia Felix, ed. Werner Daum (Innsbruck: Pingin-Verlag; Frankfurt: Umschau-Verlag, 1987), 63; Lindsay, “Nahom/NHM: Only a Tribe, Not a Place?”

70. Haram 2, CSAI.

71. Gr 326 and M 248, CSAI.

72. Ir 12, CSAI. A different inscription (Gl 1362) does use the expression “the land of Ḥashīd” (ʾrḍ ḤS2DM).

73. The -y is the nisba ending, while the terminal -n is the definite article. In the ancient South Arabian inscriptions, the nisba is most commonly used to express tribal affiliation (see Robin, “Tribus et territoires,” 214–15), but on occasion it was also used to indicate that a person is from a specific city or region (Avanzini, By Land and By Sea, 59, cites the example of ns2qyn, which is the nisba of Nashq, the name of a city). It functions similarly to the English gentilic -ite suffix, and thus nisba forms are often translated using -ite (for example, Nihmite). On the nisba form, see Leonid E. Kogan and Andrey V. Korotayev, “Sayhadic (Epigraphic South Arabian),” in The Semitic Languages, ed. Robert Hetzron (New York: Routledge, 1997), 227–28, 230; Norbert Nebes and Peter Stein, “Ancient South Arabian,” in The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia, ed. Roger D. Woodward (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 151; Peter Stein, “Ancient South Arabian,” in The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook, ed. Stefan Weninger (Göttingen, Ger.: de Gruyter Mouton, 2011), 1050–51.

74. See Neal Rappleye, “Ishmael and Nahom in Ancient Inscriptions,” presentation given at the 2022 FAIR Conference, August 3, 2022. Prior to my presentation at the FAIR Conference, only brief mention of any inscriptions beyond the three altars of Biʿathtar (see n. 79 herein) had been made by Warren Aston and myself in a previous publication (cited in n. 80 herein). See Aston, “History of NaHoM,” 90–93; Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia, 78–79.

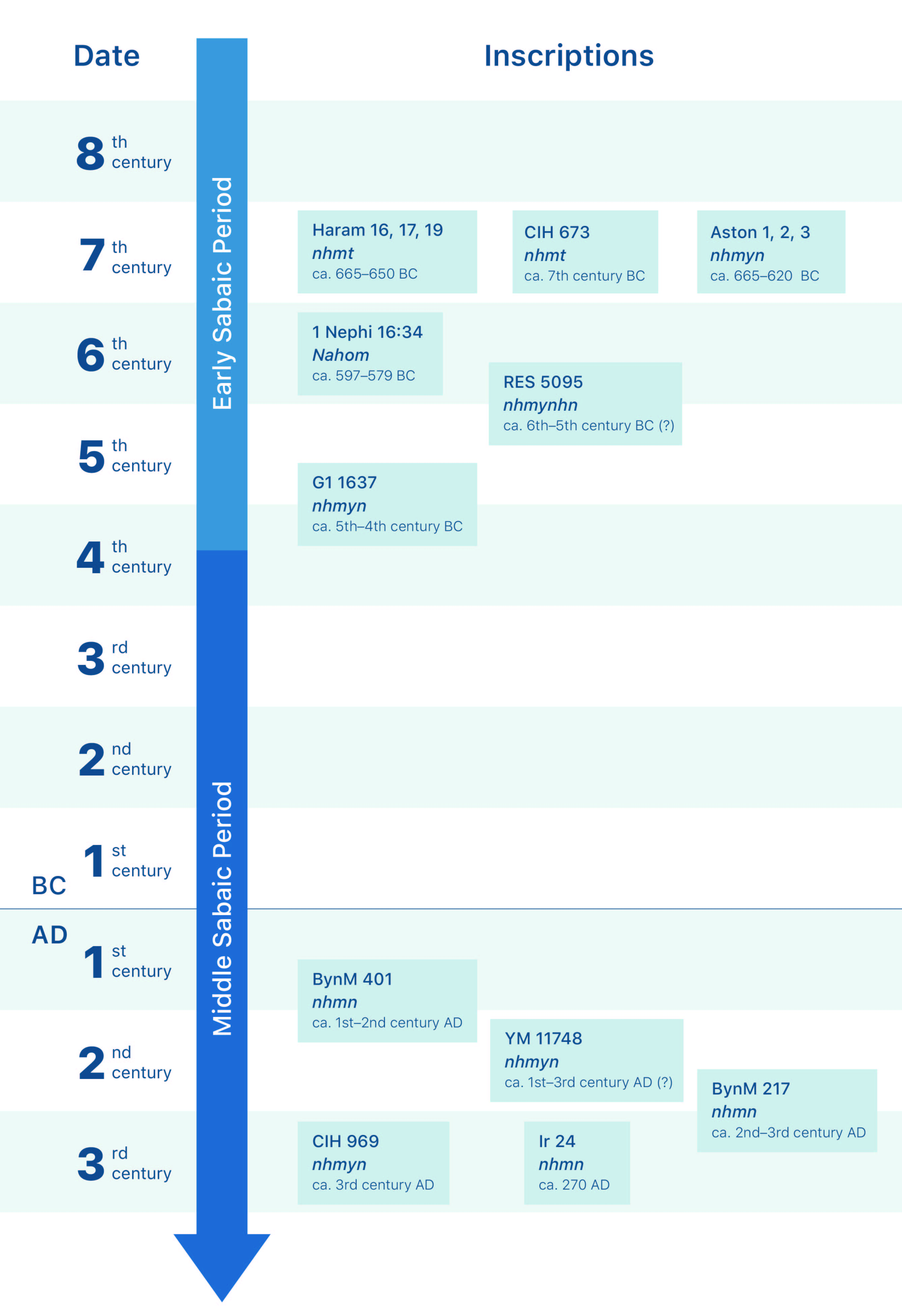

75. CIH 969, CSAI, name transliterations mine. See also CIH 969 (Bombay 40), in Mayer Lambert, “Les Inscriptions Yéménites du Musée de Bombay,” Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 20 (1923): 80–81; Alessandra Lombardi, “Le stele sudarabiche denominate ṢWR: monumenti votivi o funerari?,” Egitto e Vicino Oriente 37 (2014): 171. For the dating, see K. A. Kitchen, Documentation for Ancient Arabia, 2 vols. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1994–2000), 2:164.

76. YM 11748, CSAI. See also Jacques Ryckmans, Walter W. Müller, and Yusuf M. Abdallah, Textes du Yémen antique inscrits sur bois (Leuven, Belg.: Institut Orientaliste, Université Catholique de Louvain, 1994), 46–50, pl. 3A–B. See pages 12–13 for the dating of the collection.

77. RES 5095 (Ry 347), CSAI. See also al-ʿAẓm 1 (Ry 347) and facsimile, in Gonzague Ryckmans, “Inscriptions sud-arabes: Septième série,” Le muséon: revue d’études orientales 55 (1942): 125–27; Fakhry, An Archaeological Journey to Yemen (March–May 1947), 1:53, no. 42; 55, fig. 21; Albert Jamme, “Un désastre nabatéen devant Nagran,” Cahiers de Byrsa 6 (1956): 166; Albert Jamme, Miscellanées d’ancient arabe IX (Washington, DC: self-pub., 1979), 87. The -nhn ending of nhmynhn makes it the plural or dual form of nhmyn. See Kogan and Korotayev, “Sayhadic (Epigraphic South Arabian),” 228; Nebes and Stein, “Ancient South Arabian,” 152; Stein, “Ancient South Arabian,” 1051.

78. Gl 1637, CSAI. See also J. M. Solá Solé, “Inschriften von ed-Duraib, el-Asāhil und einigen anderen Fundorten,” in Maria Höfner and J. M. Solá Solé, Inschriften aus dem Gebiet zwischen Mārib und dem Ğōf (Vienna: Der Öserreichischen Akadaemie der Wissenchaften, 1961), 40. For the dating, see Kitchen, Documentation for Ancient Arabia, 2:208. Some have interpreted nhmyn in this instance as “stonemason.” See GL1637, Glaser Collection, accessed June 6, 2023, http://glaser.acdh.oeaw.ac.at/gl/rec/110003337. The CSAI Database considers both translations a viable possibility. Typically, in a compound nisba (as found in this inscription with nhmyn mydʿyn), both are considered references to the individual’s tribal affiliations, with one possibly being the subtribe of the other. Also, this inscription’s location near Ṣirwāḥ makes it a likely reference to the Nihm since (1) Ṣirwāḥ is in the Ḫawlān region, which borders the Nihm (see Hermann von Wissmann, Zur Geschichte und Landeskunde von Alt-Südarabien [Wien: Böhlau, 1964]), (2) another inscription from Ṣirwāḥ refers to Nihmites (see RES 5095 [Ry 347], CSAI), and (3) evidence suggests that Ṣirwāḥ controlled at least part of the Nihm in the early first millennium BC (see Frantsouzoff, Nihm, 1:22, 66, 76–77), thus making it likely that Nihmites would be subservient to the Ṣirwāḥ tribe and make votive offerings at their temple.

79. See Christian Robin and Burkhard Vogt, eds., Yémen: au pays de la reine de Saba’ (Paris: Flammarion, 1997), 144; Wilfried Seipel, ed., Jemen: Kunst und Archäologie im Land der Königin von Saba’ (Wien: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 1998), 325; Alessandro de Maigret, ed., Yemen: Nel paese della Regina di Saba (Rome: Palazzo Respoli Fondazione Memmo, 2000), 344–45; John Simpson, ed., Queen of Sheba: Treasures from Ancient Yemen (London: The British Museum, 2002), 166–67; Kitchen, Documentation for Ancient Arabia, 2:18; Norbert Nebes, “Zur Chronologie der Inschriften aus dem Barʾān Temple,” Archäologische Berichte aus dem Yemen 10 (2005): 115, 119. On the Barʾān archaeological site, see Burkhard Vogt, Werner Herberg, and Nicole Röring, “Arsh Bilqis”: The Temple of Almaqah of Bar’an in Marib (Sanaʿa: Deutsche Archaologishe Institut, 2000); Burkhard Vogt, “Les temples de Maʾrib: Barʾân (aujourd’hui ʿArsh Bilqîs), temple d’Almaqah,” in Robin and Vogt, Yémen, 140–41; Burkhard Vogt, “Der Almaqah-Tempel von Barʾân (‘Arsh Bilqīs),” in Seipel, Jemen, 219–22; Jochen Görsdorf and Burkhardt Vogt, “Radiocarbon Datings from the Almaqah Temple of Barʾan, Maʾrib, Republic of Yemen: Approximately 800 CAL BC to 600 CAL AD,” Radiocarbon 43, no. 3 (2001): 1363–69. Initial reports dated temple 3 and Biʿathtar’s inscriptions to the sixth to seventh centuries BC (see Robin and Vogt, Yémen, 144; Seipel, Jemen, 325; Maigret, Yemen, 344–45; Simpson, Queen of Sheba, 166–67; Kitchen, Documentation for Ancient Arabia, 2:18), but temple 3 and Biʿathtar’s inscription were later redated to a slightly earlier period, around the seventh to eighth centuries BC (see Nebes, “Zur Chronologie der Inschriften aus dem Barʾān Temple,” 115, 119; and Vogt, Herberg, and Röring, “Arsh Bilqis”). In either case, I believe the ruler named Yadaʿil mentioned in the inscription is most likely Yadaʿil Dhariḥ, son of Sumhuʿali, who conducted several temple-building projects in the early to mid-seventh century BC, and thus I consider the seventh century BC the most likely dating of the text. On Yadaʿil Dhariḥ, son of Sumhuʿali, see William D. Glanzman, “An Examination of the Building Campaign of Yadaʿʾil Dharīḥ bin Sumhuʿalay, mukarrib of Sabaʾ, in Light of Recent Archaeology,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 33 (2003): 183–98; Avanzini, By Land and By Sea, 114.

80. See kbr nhmt in CIH 673, and kbr nhmtn in Haram 16, Haram 17, Haram 19, CSAI. For the dating of these inscriptions, see Kitchen, Documentation for Ancient Arabia, 2:120 (the Haram texts), 139 (CIH 673). For the Haram texts, see also Christian Robin, Inabba’, Haram, Al-Kāfir, Kamna et al-Ḥarāshif, 2 vols. (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1992), 1:85–89. On interpreting these as references to Nihm, see Neal Rappleye, “An Ishmael Buried near Nahom,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 48 (2022): 36, 44 nn. 21–23. The -t(n) ending in these texts may indicate that this is the collective form of the NHM name. Compare A. F. L. Beeston, “Ḥabashat and Aḥābīsh,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 17 (1986): 5–9, who argues that ḥbs2t and ḥbs2tn are collective forms of the ḤBS2 name (Ḥabash). Hence, the expression mlk ḥbs2tn is translated “Habashite king” (CIH 308, CSAI). The expression kbr nhmt or kbr nhmtn is a similar construct of high-ranking leader (kbr) + tribal/group name (nhmt, nhmtn), and I would propose it should similarly be translated as “chief of the Nihmites.”

81. See Ph. 160 n. 20 (JML-F-74), in Albert van den Branden, Les Textes Thamoudéens de Philby, 2 vols. (Louvain: Institut Orientaliste and Publications Universitaires, 1956), 1:52. Christian Julien Robin and others, A Stopover in the Steppe: The Rock Carvings of ʿĀn Jamal near Ḥimà (Region of Najrān, Saudi Arabia) (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 2022), 266, translate nhmyn as “stonecutter” here but acknowledge that Nihmite is also a possible translation (p. 451). Since the nisba form is completely unknown in the local (Himaitic) inscriptions from this region (per Robin and Gorea), the use of nhmyn indicates that this individual was most likely a caravaneer/traveler from South Arabia. See Christian Julien Robin and Maria Gorea, “L’alphabet de Ḥimà (Arabie Séodite),” in Alphabets, Texts and Artifacts in the Ancient Near East: Studies Presented to Benjamin Sass, ed. Israel Finkelstein, Christian Robin, and Thomas Römer (Paris: Van Dieren Éditeur, 2016), 310–75. Van den Branden (pp. 23–24) argued that these texts should be dated to between the late second and late third centuries AD, but others had dated them to much later, around the fifth to sixth centuries AD. Robin and Gorea (pp. 330–35) indicate that Himaitic texts are currently undatable, hence I have simply used the vague designation of “pre-Islamic” to define the date of this inscription. See also Mounir Arbach and others, “Results of Four Seasons of Survey in the Province of Najran (Saudi Arabia): 2007–2010,” in South Arabia and Its Neighbours: Phenomena of Intercultural Contacts, ed. Iris Gerlach (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2015), 37–39.

82. Solá Solé, “Inschriften von ed-Duraib, el-Asāhil und einigen anderen Fundorten,” 40: “bekannten Stammesnamen nhm,” translation mine.

83. See Ryckmans and others, Textes du Yémen, 47.

84. Norbert Nebes, commentary on “Les autels du temple Bar’ân à Ma’rib,” in Robin and Vogt, Yemen, 144. I explore the potential implications that relocating (or extending) Nihm to the north of Jawf has on equating it with Nahom in Neal Rappleye, “The Nahom Convergence Reexamined: The Eastward Trail, Burial of the Dead, and the Ancient Borders of Nihm,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship (forthcoming).

85. Mounir Arbach, Les noms propres du Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum, pars IV: Inscriptiones Ḥimyariticas et sabaes continens (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 2002), 15. Abrach is defining his category III names as “Names of Tribes and Ethnic Groups” (“Noms de tribus et groupes ethniques,” translation mine). He includes two types of names in this category: (1) “names which are preceded by the term s2ʿb, which signifies ‘tribe,’” and (2) “those designating the inhabitants of a territory or a country” (“les noms qui sont précédés par le terme s2ʿb, qui signifie ‘tribu’, ceux désignant les habitants d’un territoire ou d’un pays,” translation mine). Since nhmyn is not preceded by s2ʿb, its inclusion in this category as an ethnique name (see p. 295) rather than a tribal name logically means it is the second of the two types—a name “designating the inhabitants of a territory or a country.”

86. Burkhard Vogt, commentary on catalog no. 240, in Seipel, Jemen, 325: “dem Gebiet Nihm, westlich von Maʾrib,” English translation in Simpson, Queen of Sheba, 166. Compare Maigret, Yemen, 345: “della zona di Nihm a [ov]est di Marib,” translation mine.

87. See von Wissmann, Zur Geschichte und Landeskunde von Alt-Südarabien, 96–97, 294–95 (map), 307–8. More recently, Jan Retsö, The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads (New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), 564, followed von Wissmann in presenting both a northern and southern Nihm in pre-Islamic times.

88. Peter Stein, Die altsüdarabischen Minuskelinschriften auf Holzstäbchen aus der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek in München, 2 vols. (Tübingen, Ger.: Ernst Wasmuth Verlag, 2010), 1:22: “Eine Übersicht der genannten Orte sowie weiterer identifizierbarer Toponyme, welche in den bekannten Minuskelinschriften,” 22 n. 43, 23 fig. 1, translation courtesy of Stephen O. Smoot. On the map, NHM is in the category of “other place, tribal, or regional names mentioned in the minuscule inscriptions” (“anderer in den Minuskelinschriften erwähnter Orts–, Stammes– oder, Landschaftsname,” translation courtesy of Stephen O. Smoot). Stein indexes the names of tribes (stamm) and nisba (nisbe) as toponyms (toponyme), illustrating more broadly that tribal names are, in fact, treated as toponyms by some scholars of ancient South Arabian studies, contrary to the assertion of Robin that tribal names “are not toponyms” (personal communication to RT, July 27, 2015, quoted in RT, “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia”).

89. James K. Hoffmeier, “The (Israel) Stela of Merneptah,” in The Context of Scripture, 3 vols., ed. William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger Jr. (Boston: Brill, 2003), 2:41.

90. James K. Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 27, summarizing the argument of Göstra Ahlström. See also pages 28–30.

91. J. Maxwell Miller and John H. Hayes, A History of Ancient Israel and Judah, 2nd ed. (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006), 42.

Figure 1. The boundaries of the Nihm district, ca. 2015. Map data: Google, © 2021 Terrametrics.

Figure 1. The boundaries of the Nihm district, ca. 2015. Map data: Google, © 2021 Terrametrics. Figure 2. The Nihm tribal territory, ca. 1986. Map data: Google, © 2021 Terrametrics.

Figure 2. The Nihm tribal territory, ca. 1986. Map data: Google, © 2021 Terrametrics. Figure 3. Nihm tribal territory, according to Hamdānī (tenth century AD). Map data: Google, © 2021 Terrametrics.

Figure 3. Nihm tribal territory, according to Hamdānī (tenth century AD). Map data: Google, © 2021 Terrametrics. Figure 4. Timeline of select references to the NHM name in South Arabia.

Figure 4. Timeline of select references to the NHM name in South Arabia.